The Living Daylights was the fifteenth official (i.e., Eon-produced) Bond film and the first to star Timothy Dalton after a string of seven films with Roger Moore as 007. It was also the eleventh and last Bond film scored by John Barry, who had been with the franchise for twenty-five years since its inception with Dr. No in 1962. Barry’s decision to leave the Bond legacy behind was in part driven by creative differences between himself and the Norweigian band a-ha, who wrote and performed the film’s title song, and in part by a feeling of limitation in the style of Bond music. (Though it must be said that Barry was slated to score the next Bond film, Licence to Kill, and was in talks to score Tomorrow Never Dies, several years later. Both projects, however, ended up with another composer.) After scoring The Living Daylights, Barry explained of working on Bond films that

“It lost its natural energy. It started to be just formula, and once that happens, the work gets really hard. The spontaneity and excitement of the original scores is gone, so you move on.”

Even so, Barry’s score for The Living Daylights could hardly be chalked up to mere formulaic repetition. Of course, there are several aspects that clearly relate the score to previous Bond films. But as we shall see in the following film music analysis, Barry continued to experiment with the Bond style, furthering the symphonic style he began to cultivate in Moonraker and offering new takes on his more established techniques.

The James Bond Theme

The Gunbarrel Sequence

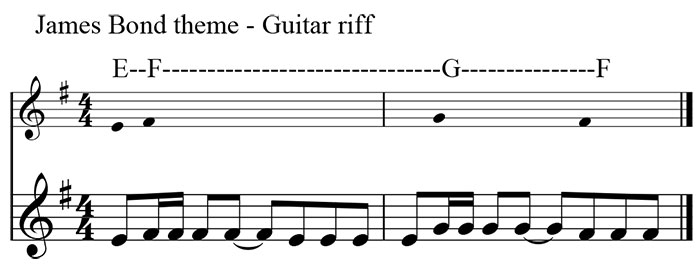

As with all of his scores for the Roger Moore Bond films, Barry keeps the opening gunbarrel sequence within an orchestral milieu through the use of string instruments on the Bond melody. Here’s a brief rundown of the instrumentations Barry used on this melody in the Moore films:

- The Man with the Golden Gun – Strings only

- Moonraker – Trumpets and strings

- Octopussy – Trumpets and strings

- A View to a Kill – Clarinets and strings

In The Living Daylights, Barry again employs the trumpets and strings on the Bond melody:

The Rest of the Film

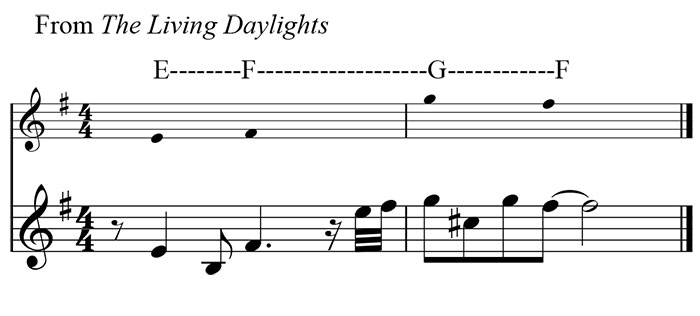

The most obvious change Barry made to some statements of the Bond theme is the addition of a synthesized rhythm track mixed with the orchestra, which he included for its “more up-to-date sound.” More subtle, however, is the way in which Barry re-fashions the theme’s original guitar riff into a new melody. Along with the following score examples, compare the melody at 0:08 in the above clip with that of 0:09 in the clip below:

While the latter melody is indeed a new addition to the Bond musical family, its relationship to the older tune cleverly expands the style in a very organic and subconsciously suitable way.

The Title Song/Theme

As with the other Bond films, Barry uses the title song, “The Living Daylights”, within the film proper. Here’s how we first hear the song in the film’s main titles:

Unlike most other Bonds, Barry relies on the song more as an occasional theme than as a pervasive main theme. When it does appear, it is usually with the type of synthesized rhythm track mentioned above as accompaniment to action scenes, one example being the final shootout between Bond and the Russian General Koskov (the melody that enters at 0:13 is from the song’s B section—just before the song’s title lyrics come in—heard at 1:08 in the clip above):

It is here that Barry’s experiments with the Bond style are perhaps the most palpable. For, the relatively minor use of the title song leaves more room to expand other aspects of the score, as we shall see.

Other Themes

Necros’ Theme – “Where Has Everybody Gone”

Like Oddjob in Goldfinger or Kidd and Wint in Diamonds Are Forever, Barry gives Necros, the main henchman in The Living Daylights, his own leitmotif. But a key difference is that the leitmotif is first heard as a rock song called “Where Has Everybody Gone?”, which Barry fashioned from his instrumental motif for the character, and which Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders wrote the lyrics for and also performed. Necros himself often plays the song through a set of Walkman headphones that doubles as his weapon of strangulation. Thus, in this form, the leitmotif is actually heard and controlled by the character it represents. This would be like Kidd or Wint whistling their own theme. While it may sound like a corny device for film scoring, the aggressive rock flavour of the song renders it an appropriate sign of nearing danger when it appears.

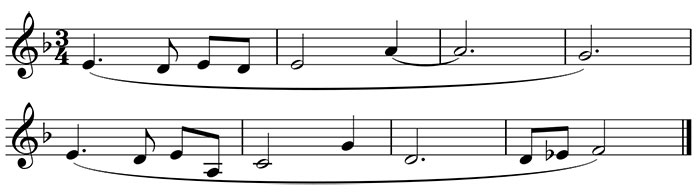

Below is the song’s melody in score and its full form in the audio (it’s the first 30 seconds that appear most frequently in the film):

The leitmotif, however, also makes its way into the non-diegetic and instrumental accompaniment, meaning that the characters now do not hear the music. In the following clip, notice how the song begins as diegetic music heard through Necros’ headphones a few times, then, when he battles one of the servants, how the same theme is transferred into the non-diegetic score at 1:47 as accompaniment for the fight scene.

The Love Theme – “If There Was a Man”

In most Bond films, Barry employs the title song as a love theme between Bond and the film’s leading lady. But in The Living Daylights, Barry’s love music enters as a separate theme first heard when Bond tells the cellist Kara Milovy that her playing at a concert was “exquisite” (beginning at 0:32):

The theme then recurs in other scenes where the focus is on these characters’ emotional connection, and culminates in the vocal version of the theme in Barry’s song, “If There Was a Man”, heard over the end credits (also performed and with lyrics by Hynde). The theme thus functions exclusively as a love theme in the score, an approach that allowed Barry the flexibility to compose other music with a different function for the score. In short, this technique allows for a score with a greater diversity of themes than one that draws primarily from the title song.

Why would he have preferred to work with new themes than with the usual title song? One can only conjecture. But as we have seen, there was certainly conflict between Barry and a-ha, who wrote the title song. As Barry put it, working with the three members of a-ha was like “playing ping-pong with four balls. They had an attitude which I really didn’t like at all. It was not a pleasant experience.” With such discontent about the collaboration, it is not surprising that the title song plays a much smaller role than in most other Bond films, appearing only four times (plus once in the main titles) compared to seven times (plus once in the end credits) for “If There Was a Man”. Even so, it may simply have been the case that Barry felt the title song more suitable for action scenes than love scenes. It is surely no coincidence that the other Bond film for which Barry composed a separate love theme was On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, in which the title song became the accompaniment to the chase scenes near the end of the film.

Ostinatos

Ostinatos are a substantial component of all of Barry’s Bond scores. But with Moonraker, we began to see more of a symphonic style emerging that focused less on direct repetition and more on the development and contrast of musical ideas. Barry employs the same approach in The Living Daylights, though with even more emphasis on development and contrast. In the pre-title sequence, for instance, we hear a two-chord pattern begin as one of the double-0 agents prepares to climb a cliff, adding an appropriately suspenseful atmosphere:

After only two statements, this pattern changes to an ominous three-chord pattern that coordinates with a man’s shadow entering over the agent’s grappling hook at the top of the cliff, signalling the man’s villainous character. Then, as this villain drops the message “Smiert Spionem” (death to spies) down to the agent, the original two-chord pattern returns, but now enhanced with a wavering violin melody. Barry then shifts this melody up an octave after only one statement, raising the tension as the villain cuts the agent’s lifeline. Successive statements of material are thus kept to only two in this scene, allowing the music to closely mirror our changing emotional responses to the situations onscreen. Watch the scene here from 2:19:

Barry’s symphonic style is even more evident in the scenes in Afghanistan, when Bond joins forces with the Mujahideen people (the Afghan resistance). As the group travels across the desert, we hear an ostinato on the small scale, the medium scale, and the large scale unfold simultaneously. On the small scale, a short rising violin line is the first element to be repeated at 0:05 below. A few bars later at 0:16, we realize that there is a four-chord pattern that begins to repeat on a medium scale. In the second statement of this four-chord pattern at 0:16, Barry adds a trombone and horn melody. And on the large scale, the first two statements of the four-chord pattern are then repeated as large “blocks” of music at 0:32 with changes in scoring, the rising violin line shifting up an octave and the trombone and horn melody moving to the trumpets. Hear this portion of the cue below from 0:00 to 1:05:

The overall result is a complex structure based on repetition, variation, and addition that, over the first four statements of the four-chord pattern, can be represented schematically as follows:

Violin Line: AAAA AAAA A’A’A’A’ A’A’A’A’

Four Chords: B B’ B B’ ’

Large Blocks: C C’

A’= higher octave

B’= added melody

B’ ’ = rescoring of added melody

C’ = rescored version of C

This kind of structure creates a sound that is highly unified through the economy of material but that remains fresh with each statement due to the variations and additions Barry makes. In short, it is a deceptively simple construction.

Diegetic Music

One noticeably new musical feature of The Living Daylights is its use of classical music as diegetic music (music that the characters actually hear). Since Bond’s love interest, Kara Milovy, is a classical cellist, this choice of music is entirely appropriate and reinforces the classy and sophisticated associations of the social world that Bond inhabits. But like much diegetic film music, the pieces relate directly to the geographical locations the characters visit. When Bond and Milovy arrive in Vienna, we hear the Viennese waltz Wein, Weib, und Gesang by the inimitable Johann Strauss, Jr., who was known as “The Waltz King” during his lifetime (in the film, we hear from 7:20 of the following clip):

Bond then attends a performance of The Marriage of Figaro by Mozart, a composer who spent much of his life in Vienna. Milovy also performs in an orchestra in Czechoslovakia, hence we hear her practicing the Cello Concerto of the Czech composer Dvořák. And at the end of the film, the Russian aspect of the plot is emphasized by Milovy’s performance in the Variations on a Rococo Theme by Tchaikovsky.

Conclusion

After scoring The Living Daylights, John Barry felt that he had written all that he could offer for the Bond franchise. But although his score for the film retains several aspects that characterized his earlier Bond scores, we nevertheless hear new elements and further extensions of ideas introduced in his other Bond scores. As we saw, a number of action cues were adorned with a new synthesized rhythm track. And while Barry still drew on the well-established technique of reusing the title song within the film proper, he minimized the song’s appearances to make room for two other themes that are a more prominent part of the score: the theme for the henchman Necros, which became the basis of the song “Where Has Everybody Gone?”, and the love theme for Bond and Milovy, which was the basis for the song “If There Was a Man”. Furthermore, Barry’s use of ostinatos was even more influenced by a symphonic mode of thought than before as they usually turned to varied or contrasting material after only two statements. Finally, the diegetic classical pieces by Dvořák, Mozart and Johann Strauss, and Tchaikovsky reinforce the film’s Czechoslovakian, Austrian, and Russian aspects, respectively. With such a diversity of music, it is no wonder the score continues to be one of Barry’s most highly regarded Bond scores.

Coming soon… A Summary of John Barry’s Changing Bond Style

Oh man I can’t believe mine is the only comment. Thanks so much for this article. I knew, watching the movie in 1989, that this was a way more evolved Bond score. I don’t know jack about composition but I could tell it was something totally fresh. It definitely elevated the movie and made it feel so much MORE than a Moore movie. This score has so much meat on the bones.

Yes, I agree! Too bad that a-ha left such a bad impression on Barry that he didn’t want to return after this one (though as I say in the article, he was in talks for future Bond films anyway). I think that might be why he unusually doesn’t make much use of the title song in the score. And it might also be why there’s another worded song that’s used much more – the theme for Necros. Maybe he thought of that theme as the secondary theme that really defines this film, just as the title song usually does in his other Bond scores.

This analysis is fantastic, very meticulous and deep at the same time. It gives a perfect overview of this fantastic symphony for a unique film. The chemistry between Timothy Dalton and Maryam D’Abo is simply volcanic.