John Barry’s career as a composer for the James Bond franchise spanned twenty-five years and twelve films beginning with his collaboration with Monty Norman on the Bond theme for the very first Bond film, Dr. No in 1962, and ending with the The Living Daylights in 1987. After Dr. No, Barry went on to score eleven Bond films on his own.

Across these eleven films, there are certainly recurring elements that form a distinctive style for Bond scoring that Barry firmly established with Goldfinger, his second solo Bond score. But at the same time, Barry treated these elements flexibly, developing them further, adding new elements or excluding old ones, sometimes at the request of the filmmakers. Hence, although Barry’s Bond style was always recognizable, these sorts of changes kept the music sounding fresh even while it remained familiar enough to form a strong connection with previous Bond scores. The following film music analysis traces the progression of four key features in Barry’s changing Bond style:

- The James Bond Theme

- The Title Song

- Other Themes

- Ostinatos

In addition to these four features, I will also discuss the filmmakers’ influence on Barry’s Bond scores.

1. The James Bond Theme

Of course, the James Bond theme appears in all of Barry’s Bond scores, most often fragmented and rescored in a slow tempo to create a suspenseful atmosphere. But the way in which its familiar jazz-scored version appears evolved with time. Not only is it always heard with the famous gunbarrel sequence, but it also usually appears in the pre-title sequence at the start of each film. Within the film proper, though, its function changed more than once.

With the first Bond film, Dr. No (scored by Monty Norman), it was used to project Bond’s suave, cool character, as when he is introduced in the casino:

Barry followed this use of the Bond theme in From Russia with Love, as when Bond arrives at a hotel and proceeds to examine his room for listening devices (from 4:23 below):

In Barry’s next two scores, however, Goldfinger and Thunderball (the next two Bond films), this particular scoring of the Bond theme essentially disappears outside of the gunbarrel sequence. Instead, Barry weaves the theme into each film’s title song, thereby creating a more organic mixture of musical material and allowing him to rely far more on the title song and less on the Bond theme without neglecting it altogether. Notice the Bond accompaniment in the “Goldfinger” song below at 0:52 and a little of the theme’s B section near the end at 2:30:

…and in the “Thunderball” song below at its very start (the Bond theme’s B section) and at 0:37 (the Bond accompaniment):

After these films, the jazz-scored Bond theme was associated with action scenes in which Bond has the upper hand, as in You Only Live Twice, in which he takes down a fleet of enemy helicopters in Q’s flying device, “Little Nellie” (heard from 0:21):

…or in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, in which Bond and his allies come to the rescue of Bond’s fiancée Tracy. (In this latter case, however, Barry was asked to insert the theme against his will.) In Barry’s scores that followed, Diamonds Are Forever, The Man with the Golden Gun, and Moonraker, the jazzy form of the Bond theme was generally confined to the gunbarrel sequence and perhaps the pre-title sequence. In Octopussy, because the film was in competition with the unofficial Bond film Never Say Never Again, the theme appeared a record nine times, most prominently during a car chase in which Bond does not have the advantage until the very end of the scene (heard at 1:23):

This type of usage of the theme returned in Barry’s next (and last) two Bond scores, A View to a Kill and The Living Daylights. Thus, beyond merely signifying the film’s protagonist, the theme’s function underwent several subtle changes over the years.

2. The Title Song

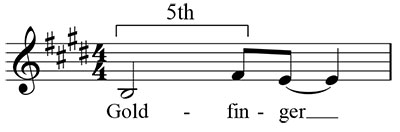

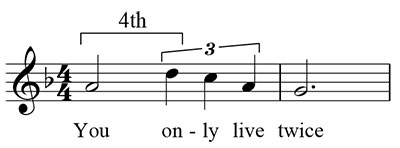

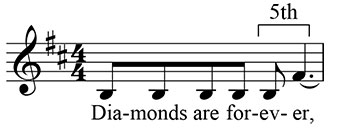

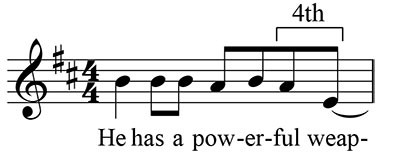

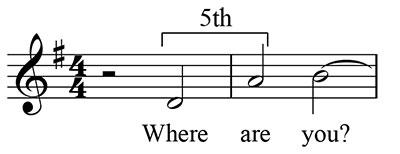

For Barry, the title song was a crucial aspect of a Bond score since he always drew on its material to fashion a good portion of each score. With Goldfinger, Barry established the technique of beginning each song with a distinctive figure or two. While this technique was partly tied to the attempt to sell soundtrack albums, it also had a functional aspect in that Barry generally employed these figures as recurring motives in the film. Notably, his title songs often open with the interval of a fourth or fifth, making them easy to identify when they return:

Goldfinger

You Only Live Twice

Diamonds are Forever – Accompaniment

Diamonds are Forever – Melody

The Man with the Golden Gun

“Where Are You?” from Moonraker

Although the function of the title song remained more consistent than the Bond theme over Barry’s career, it too experienced some changes in its application. As we saw in Goldfinger, Barry utilized the title song as a generalized main theme that not only accompanied Goldfinger himself as a kind of leitmotif, but also suspenseful scenes, a car chase, and a landscape scene as well. With the enormous success of Goldfinger, both film and music, Barry clearly felt that he had hit on a winning technique, so continued to employ it in his next five Bond scores. (Though in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, it’s not the instrumental title theme that acts as a main theme, but the vocal song “We Have All the Time in the World”, which appears in a montage within the film proper.) Moreover, the technique allowed Barry to work with new music in each Bond film while still keeping within the style he had created.

With Moonraker, we saw that Barry’s style began to take on more symphonic characteristics, especially in the development and reshaping of musical ideas rather than their repetition, likely as an influence from John Williams’ success with Star Wars only two years earlier. Consequently, those aspects of Barry’s Bond scores that had previously played more minor roles—the Bond theme and ostinatos—could take on a larger role in the film without becoming tiring. In other words, the symphonic style allowed Barry more melodic variety in his options for a Bond score. Rather than relying mainly on the title song, he could now incorporate more new music through the use of new developments of the Bond theme and more developmental ostinatos.

With so many ideas at Barry’s disposal, the title song no longer needed to accompany so many different emotional situations. Thus, he confined its use almost exclusively to love scenes. This narrower function continued into his subsequent scores for Octopussy and A View to a Kill. This scene from Octopussy is typical of Barry’s use of the title song in these later Bond scores:

In Barry’s final Bond score, The Living Daylights, the title song’s appearance is reduced to the point of being negligible. It occurs only during a couple of suspense scenes and more prominently in a couple of chase scenes (with a segment of the song’s B section, which is harder to recognize). But it is important to remember that Barry had very little to do with this song, as his creative difficulties with a-ha, the band who wrote and performed the song, are well known. For the love scenes, Barry instead wrote a theme of his own that became the song “If There Was a Man”, heard over the end credits. Hence, the same basic technique is still in evidence, though with a shift in the song’s placement due to Barry’s waning control over the title song. (This loss of control was partly why Barry refused when asked to return to the Bond franchise for Tomorrow Never Dies.)

3. Other Themes and Songs

Henchmen’s Leitmotifs

Another feature of Barry’s Bond style is the use of themes, songs, and motives (i.e., distinctive melodies) other than the Bond theme and title song. In some cases, these additional themes are leitmotifs for the villain’s henchmen, examples being Oddjob from Goldfinger, Kidd and Wint from Diamonds Are Forever, and Necros from The Living Daylights, all of which I’ve discussed in these posts. Whether or not a henchman received a leitmotif seems not to have depended on any particular aspect of the film. Rather, it was most likely a way to offer melodic diversity in the score. The majority of Goldfinger, for instance, is based on the title song, so the leitmotif provides some welcome contrast. In Diamonds Are Forever, several scenes contain diegetic jazzy lounge music, and many of the action scenes are very sparsely scored, forcing Barry to make the most of the relatively small amount of non-diegetic music used in the film. And in The Living Daylights, Barry’s marginalization of the title song left him plenty of room to fill with other themes.

The 007 Theme

Barry employed the 007 theme in five Bond films beginning with From Russia with Love and continuing into Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Diamonds Are Forever, and Moonraker. He seems to have used it as a kind of counterweight for each of these films in that, in the four Connery Bond films in which it appears (the first four above), its buoyant, active sound provides the action with some levity, especially in Diamonds Are Forever, where the overall dark tone of the film is considerably lightened when Bond takes control of Blofeld’s escape pod and tosses it about. Compare these to its appearance in Moonraker, where the already light and somewhat humourous tone of the film is made more serious by a noticeably slowed down version of the theme:

Here it is in From Russia with Love:

And here it is in Moonraker (starting at 1:45):

Landscape Themes

Occasionally, Barry wrote a separate theme to accompany shots of landscapes, as in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (at 0:19):

and Moonraker (at 0:09):

Like the leitmotifs for henchmen and the 007 theme, these landscape themes offer melodic contrast within Barry’s James Bond style.

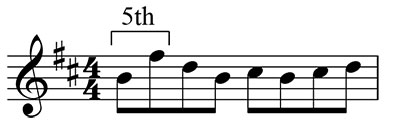

4. Ostinatos

Ostinatos—repetitions of a relatively short unit of music—are an integral part of each one of Barry’s Bond scores, primarily because they occupy so much of the score. (I would estimate as much as half of most scores.) Barry’s technique for ostinatos did not, however, remain unchanged throughout his career. In the early scores, the ostinato pattern tends to undergo only minimal change by adding short fragments of melody overtop. This keeps the engine-like drive of the ostinato intact for its entire length and works especially well in intense scenes like “The Laser Beam” from Goldfinger, where a laser beam slowly nears Bond’s groin.

As we saw with Moonraker, Barry’s approach to ostinatos began to include more contrasting material in accordance with a more symphonic style, hence breaking up the repetitions and creating a more relaxed mood appropriate for landscape scenes, space scenes, and other visual expanses. This technique was taken somewhat further in The Living Daylights, in the cue I discussed called “Mujahadin and Opium”, where a broad two-phrase melody unfolds over the ostinato, suggesting the vastness of the Afghan desert:

And yet, it’s not as if Barry continued to develop his ostinato technique in isolation from his other Bond-score components. Some themes, such as that of Kidd and Wint in Diamonds Are Forever, have an ostinato accompaniment. At other times, as in the pre-title sequence of Goldfinger, the Bond theme’s accompaniment becomes an ostinato on its own. And even a part of the title song may be used as an ostinato, as do the opening two chords of the Goldfinger title song in the cue “Dawn Raid on Fort Knox”:

And as we saw above, in his later scores, Barry’s ostinatos themselves tended to become more melodic, more like a theme. Thus, the ostinatos were one of the more flexible aspects of Barry’s Bond score style.

The Filmmakers’ Influence

While the four features discussed above form the core of Barry’s Bond style, there were sometimes other elements that made their way into some of the films at the request of the filmmakers. Perhaps the most prominent of these is the use of musical quotations, which actually originated in Marvin Hamlisch’s score for The Spy Who Loved Me with its quotes of Maurice Jarre’s themes from Doctor Zhivago and Lawrence of Arabia, as well as Bach’s Air on the G String, and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major. In the very next Bond film, Moonraker, there are quotations of Elmer Bernstein’s theme from The Magnificent Seven, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Oveture, and Chopin’s “Raindrop” Prelude. As I argued in the Moonraker analysis, the appearance of these pieces was almost certainly at the suggestion of Lewis Gilbert, who directed both this film and The Spy Who Loved Me.

In other cases, the filmmakers asked for the insertion of the Bond theme in a scene against Barry’s wishes. This occurred in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service during Bond’s helicopter rescue of Tracy in Blofeld’s mountaintop lair, and also in Diamonds Are Forever, when Bond is searching a house for Willard Whyte (just before he runs into “Bambi” and “Thumper”).

And in a few other instances, there was disagreement as to what kind of music should accompany a scene or whether music should be present at all. In the dune buggy chase in Diamonds Are Forever, director Guy Hamilton wanted comical music to match the light-hearted character of the scene. But Barry disagreed and thought the scene would be more effective scored with more serious action music to heighten the contrast and throw the parodic nature of the scene into relief. What ended up in the film was a compromise between the two sides that ironically makes it more difficult to interpret the emotional content of the scene since it incorporates both comical and serious qualities (from 2:17):

Finally, there was also the sparse use of music in many action scenes in Barry’s Bond scores of the late 1970s and early to mid 80s due to the filmmakers’ preference for a variety of sound effects in place of music, a consequence of the clearer film sound achieved with the new Dolby stereo technology. Once again, Barry disagreed with this approach, especially in Moonraker, which was released only two years after the widespread adoption of Dolby. Nevertheless, as with all of the filmmakers’ suggestions, the approach forms a part of the Bond style for these films, just not Barry’s Bond style.

Conclusion

John Barry firmly established his James Bond style in his second Bond score, Goldfinger. In that film, he employed the title song in various situations as a main theme for the film, made sparing use of the James Bond theme, and created a leitmotif for the henchman, Oddjob. Another substantial part of the score was based on ostinatos. These four components became the basis of Barry’s Bond style for the remainder of his career. But Barry never allowed this pattern to fall into monotony because most of the components—the title song, other themes (excluding the 007 theme), and ostinatos—were new with each film. And even the one constant element, the Bond theme, underwent changes in the frequency of its appearance and in its function, so that it could feel quite different even if heard with the same upbeat, jazzy scoring as before. In this way, Barry’s Bond style always offers much that is new even while continuing in a similar vein as previous Bond films. Striking the right balance between new and old was one of Barry’s many strengths as a Bond composer and surely part of the reason why his music for the James Bond legacy remains greatly admired today.

Coming soon… John Williams’ Superman March

Thanks for that excellent discussion and analysis.

It seems, then, that the “Bond theme” developed somewhat organically during the series of films (franchise). As the films continued, I noticed that they began to parody each other in subtle ways and I submit that the ‘re-casting’ of the theme is a major way to achieve that. I suppose it’s inevitable that a series of films with the same character is going to become monotonous – what new things can be possibly said? So I think Connery tended to parody the films towards the end and this was probably a reason why alternative actors were chosen – there was going to be an end point and inevitability with parody. A new “James Bond” would freshen the characterization. Connery was the most superb, but Moore tended towards the subtle tongue-in-cheek too. The 007 theme in its various incarnations became somewhat self-reflexive and, to a degree, parodying. The consistent use of a 007 “theme” also implied ‘quality assurance’ – audiences knew what they were getting, that it would be predictable but by transforming or paraphrasing the theme itself they knew to expect the unexpected.

There are marketing reasons, of course, but I regard a ‘signature’ theme as synonymous with a type of film and a ‘guarantee’ about what audiences could expect.

Newer, less familiar title music would disrupt that narrative expectation and create a newer set of expectations – so the ‘franchise’ can continue.

Sue – Yes, I would agree that the evolution of the use of the Bond theme (in its jazz-scored form) did provide a certain guarantee for audiences while giving them something new at the same time.

One use that Barry seemed to stay away from is for a “heroic escape” that Bond makes. The first really prominent example is in Hamlisch’s score for The Spy Who Loved Me, in the pre-title sequence, when Bond skis off a cliff and opens his parachute, which is a big Union Jack (at 0:58):

Michael Kamen used it in pretty much the same way in Licence to Kill, when Bond makes his escape by water skiing away with a harpoon gun:

This use of the Bond theme seems to have become common in more recent Bond films. Barry’s conception of the theme didn’t really include this function, or at least marginalized it.

I just discovered your blog and finished reading your whole Barry-Bond series. It is excellent! In your passage about other themes and songs, you neglected to mention other action themes that many of the films have. When the main theme is used as a love theme, Barry often writes an additional action theme to be used multiple times the film. In You Only Live Twice there is “A Drop in the Ocean”, in Octopussy there is “Gobinda Attacks/Yo-Yo Fight” and in A View to a Kill there’s “Snow Job/He’s Dangerous”. You also say that in “The Man with the Golden Gun, and Moonraker, the jazzy form of the Bond theme was generally confined to the gunbarrel sequence and perhaps the pre-title sequence.” The Bond theme is used for the car chase in The Man with the Golden Gun in its same form as in the gunbarrel, and in Moonraker, the form used in the pre-title freefall sequence is later used in a boat chase. Since The Man with the Golden Gun, Barry used the full-on Bond theme for chase sequences in every film. In Octopussy it’s used in the taxi chase and in the car chase on the train tracks. In A View to a Kill it’s used in the chase in Paris. And in The Living Daylights it’s used in the Gibraltar chase and in the Aston Martin chase.

Great additions, Matt! When I wrote these Bond posts, I never intended them to be comprehensive, so there are inevitably themes that go unmentioned. But it’s really nice to have your additional themes here. It’s a hope of mine to one day do a thorough examination of all of Barry’s Bond scores. Thanks again for your input.

I feel it is worth pointing out that the use of the James Bond Theme in the clips you cite from From Russia with Love and You Only Live Twice were also sequences that were ‘scored’ without Barry’s approval/participation (in a similar situation to the one mention regarding OHMSS). These scenes were done in the dub and were not intended that way by Barry. Regarding You Only Live Twice, Barry wrote the cue 6m2 for Little Nellie’s take off and first flight, and the immediate next cue for the scene is 6m3, where Bond states over the radio that he is returning to base. Notice there is no gap in the cue numbers; if Barry had intended the James Bond theme for the aerial fight, that cue would have been 6m3 and the ‘returning to base’ cue would have been 6m4. The dogfight sequence was originally intended to play without music, with the James Bond Theme ‘tracked’ (and remixed to fit) into the scene for a more lively feel.

Similarly, the train tracks chase in Octopussy that Matt S. mentions above is another case of tracking; that is, previously-composed being inserted into the sequence (either by the editor, director or music editor) where there was originally a different cue or no music written for that sequence originally by the composer.

The opening fifth interval, of course, also happens in the works of Barry’s successors and is key to a good Bond song.

On the theme song by Garbage you interestingly have: “The (B) world (C) IS (B) not (G) e (Eb)-NOUGH (B)”.