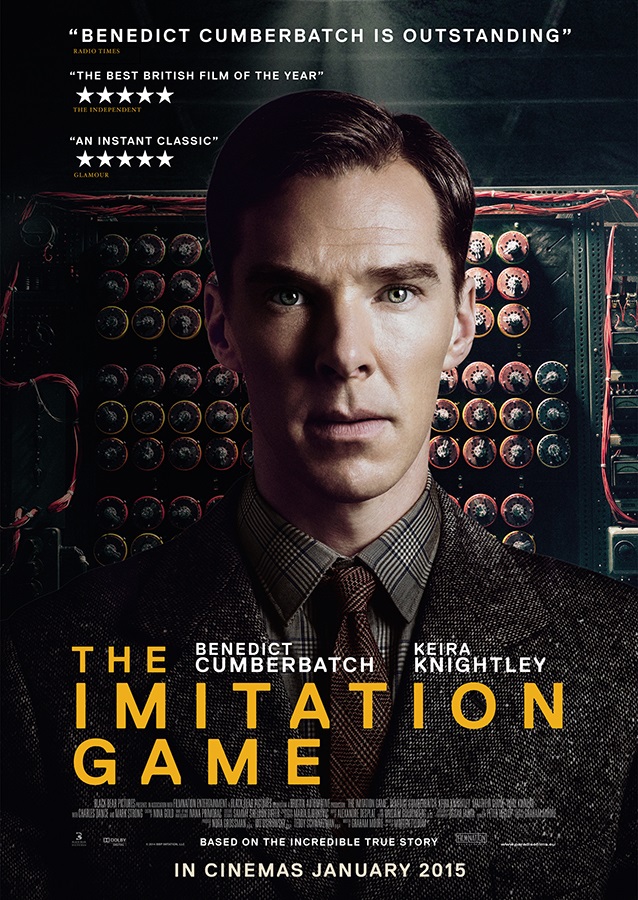

In addition to earning two Oscar nominations in 2014, Alexandre Desplat managed to score some of the year’s biggest box-office successes as all five of the films he scored ranked within the top fifty-five. These include The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Monuments Men, Unbroken, Godzilla, and The Imitation Game.

The Imitation Game revolves around the life of Alan Turing, the British mathematician, cryptographer, and computer scientist who played an instrumental role in breaking the code of the Nazi’s “Enigma machine” during the Second World War, and who pioneered the subjects of computer science and artificial intelligence.

While Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game is orchestrated much more traditionally than that for The Grand Budapest Hotel, it shares with the latter the technique of drawing on a small number of themes as a unifying device. It is these themes that I focus on below in a film music analysis of the score.

Alan Successful

This theme, which is consistently associated with Alan (Benedict Cumberbatch), could well be considered the score’s main theme as it is heard with the film’s titles and is its most prominent musical idea. It serves as an appropriate accompaniment for Alan as its musical features subtly express aspects of his personality and circumstances. Hear this theme in the clip below:

The theme begins innocuously with a motif in the piano that is repeated to form an ostinato. The broken-chord harmony of this ostinato clearly establishes the minor key of the theme. Shortly after the theme’s true melody enters at 0:40, however, the ostinato continues to move through the same minor chord, even as the harmony around it is changing. This clash of chords could well be heard to represent Alan’s staunch reluctance to “harmonize” with those around him and the “dissonance” that comes as a result.

Upon the entrance of the theme’s melody, the harmony surrounding the ostinato starts on a minor chord then shifts upward to a major chord. While this motion suggests a struggle from a negative (minor) state to a more positive (major) one, only two chords later, the harmony has, with seeming inevitability, sunk back down to the minor chord where the tune began. These motions closely reflect several of Alan’s interactions with others, in which he unwittingly places himself at a disadvantage then tries to dig himself out of a hole, so to speak. During his job interview to work at Bletchley Park, for example, where cryptographers are attempting to break Enigma, his untoward social manner earns him the dislike of Commander Denniston (Charles Dance), who is in charge of the operation. He spends the remainder of his time at Bletchley trying to avoid giving Denniston an excuse to fire him. Much the same could be said of his relationship with the other male cryptographers and the detective who is investigating him a few years after the war.

But as the name suggests, the theme is also used to highlight Alan’s major successes in the film. These include:

- Alan travelling to his prestigious job interview at Bletchley at the start of the film

- A montage showing Alan inventing the Christopher machine that is used by the cryptographic team to break the code

- Alan’s fellow cryptographers standing up for him and preventing Denniston from firing him

- The breaking of the Enigma code itself

- The description of Alan’s legacy through his breaking of the code and the many lives saved as a result, and the invention of his machine, which became the basis of the modern computer

Alan Defeated

One of the most ironic aspects of The Imitation Game is that, not only does Alan experience great success in ways that most others can only dream of, but he also suffers equally great defeats in other areas of his life, namely in the death of his boyhood love, Christopher, and his ultimate conviction for his homosexuality. The theme’s connections to these ideas are clarified by its placement in the film. It appears, for instance, when Alan is being interrogated at the police station at the very opening of the film, when the boy Alan waits in vain for Christopher to return to school after a two-week holiday (a scene that leads us back to Alan at the police station), and when we see the aftermath of the Nazi attack the cryptographers could have prevented after breaking Enigma. Listen to this theme in a solo piano version in the cue below:

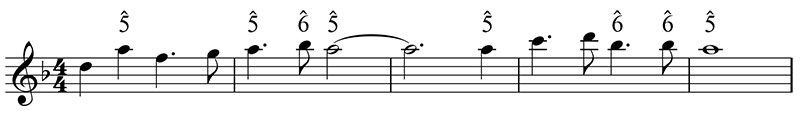

The sense of defeat is made palpable through several musical aspects of the theme. Most obviously, like the other prominent themes in the film, it is set in a minor key. Furthermore, the melody’s first two phrases both linger around and end on the fifth degree of the scale. This lack of emphasis on the first scale degree (tonic) suggests something that is incomplete and in need of resolution (to the tonic), much as Alan’s feelings for Christopher are in the film. Notice, too, that the last two notes of each phrase outline a half-step from the sixth to the fifth note of the minor scale. This particular combination of minor scale degrees (6-5) has a long history of associations with expressions of the tragic, a fitting emotion for the theme’s connection with Alan’s defeats.

Christopher

After considering the score with the film, one might believe this theme to simply represent the character of Christopher in the way that leitmotifs generally do, by drawing on musical techniques that suggest aspects of the associated character (a la John Williams or Howard Shore, for example). But in this case, the theme’s melancholic sound does not reflect Christopher’s good will and strong devotion to Alan. More importantly, the theme is only ever heard during the scenes from Alan’s childhood, which are always flashbacks in his own mind. Hence they are seen (and heard) through Alan’s emotions. The theme’s sadness, then, is a reflection of Alan’s thoughts of Christopher rather than of Christopher himself, and for this reason, it would be more accurate to consider the theme along the lines of “Alan thinking of Christopher.”

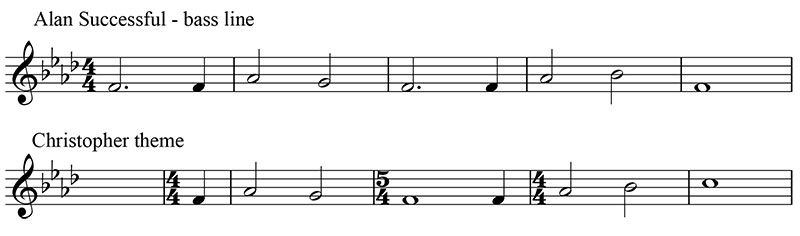

Desplat does a fine job of clarifying this interpretation as the Christopher theme possesses the very same notes and rhythms as the bass line to the Alan Successful theme. I show both melodies below transposed to a mid-range for ease of comparison:

Listen to the bass notes of Alan Successful in the main title below from 0:00-0:26:

and now compare that to the Christopher theme in the cue below from 0:13-0:33:

The only real differences are that the Christopher theme is always in a higher register, giving it more the character of a true theme, and its melody is always scored for the piano, an instrument that in film is typically used for moments of introspection, as here. But the fact that the theme is derived from the Alan bass line suggests that Christopher is literally the support for and basis of Alan’s emotions, an idea that is very consistent with Alan’s relationship with the character in the film. Desplat’s musical expression of this relationship is ingenious for both its simplicity and effectiveness.

Secrets

Whether they take the form of the coded messages of the Nazi Enigma machine, Alan’s hidden homosexuality, or Alan’s work with the British government to keep the public and Germans from realizing that the Enigma code has finally been broken, secrets are one of the film’s most pervasive narrative themes. Specifically, the film explores some of the sinister aspects that can surround secrets. The coded Enigma messages are perhaps most emblematic of this idea as they often carry directions for military offensives on the Allied forces. But there are also morally grey areas raised in connection with some of the other secrets in the film. For instance, keeping one’s homosexuality secret for several years prevents entanglements with British law (which at the time viewed homosexuality as a crime) but at the same time prevents one from having an open relationship with a member of the same sex. And keeping the breaking of Enigma secret allows more military intelligence to be gained, but at the cost of allowing many known attacks on the British to occur so as not to arouse the Nazis’ suspicion.

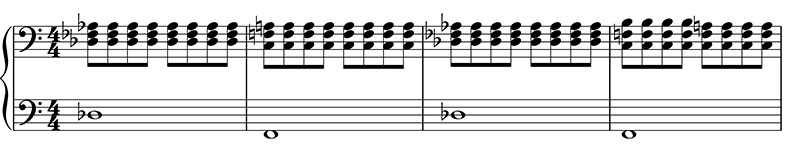

Desplat’s Secrets theme aptly expresses this mixture of negative and positive emotions by resolving a minor chord unusually into a major chord and creating an odd mixture of both cold-bloodedness and something approaching hopefulness:

In technical terms, the distance of the minor chord from the major (as measured by the chordal roots) is a minor sixth down (or major third up). Had the second chord also been minor, the chord progression would have upheld a long tradition of being associated with evil, most famously in Darth Vader’s theme from the Star Wars saga. As it is, Desplat’s progression certainly references such associations but, through the use of a major tonic chord, creates a tension between positive and negative emotions.

Conclusion

While much more traditional in its overall sound than his other Oscar-nominated score, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Alexandre Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game manages to capture much of the expressive content of the film in its four most prominent themes. Combined with the composer’s penchant for distinctive ostinatos and colorful orchestrations, the result is a score whose subtly appropriate use of musical devices allows us to more acutely feel the incredible highs and lows that define the remarkable life of Alan Turing.

Coming soon… The Theory of Everything.

Not f minor, but mode in d on f(= f dorian mode). I’ve heard bitonal passages and expected analysis of instruments imitating morse code typing sound. On subtitle “secrets”, it’s relationship is tonika-gegen, if we analyze in classic style – or rather we can analyze it as a mode change[Db – F – Db – F], little like pop-jazz.

Hi Quaziliev – Yes, I would agree with F Dorian for the theme. I was using the term minor in a looser way to mean a scale that has a minor chord as its tonic. Since my analysis didn’t rely on distinguishing the exact mode, I didn’t get into that point, but it is more precise. It’s interesting to note how flexible the mode can be while keeping the tonic the same. Notice that, although the Dorian mode that is sounding when the main melody is sounding, the music just before it enters has Db-C in the bass, so is the true minor (or Aeolian) mode.