Following on the success of his mid-1970s scores for Jaws and Star Wars, John Williams produced yet another iconic movie theme with Superman in 1978. At the initial recording session for the film, the theme made such an impact on director Richard Donner that, unable to contain himself, he exclaimed “Genius! Fantastic!”, promptly ruining the first take. The theme also leaves an indelible mark on the memories of many a filmgoer, particularly in the way it accompanies the film’s main titles, which literally fly on and off screen like the Man of Steel himself.

Thus, the Superman theme has become so inextricably linked with its filmic association that it can seem as though it is the only musical representation possible for the character. How does Williams manage to do this? As in so many of his other themes, by carefully coordinating the musical features so that they converge and provide us with a fleshed out picture of the thing it represents. In this particular case, and as many have pointed out before, the music even seems to speak the name “Superman” in its first big cadence (more on this below).

The Superman theme consists of three main components, which are in fact smaller complete themes in themselves: a fanfare, a march, and a love theme. In the following film music analysis, I discuss several of the features that contribute to the expression of the Superman theme in each of its components and over its entire structure.

The Fanfare

Below is the concert version of the Superman theme:

This version begins with the fanfare (whereas the film version omits this initial appearance), which is set in a moderate tempo and at a moderately loud dynamic. Together with the noble brass melody and the subtle but dramatic timpani roll, it is as though a great storyteller is preparing us to hear a mythic tale of epic proportions, the musical equivalent of Star Wars’ famous “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”.

Structurally, the fanfare begins with two motives that outline a perfect fifth and fourth, intervals commonly used to denote heroism. But these intervals go beyond the merely heroic since they are based on only two different notes of the scale: the tonic (the scale’s first note) and dominant (its fifth note). Together, these notes suggest the most restful chord in any key, the tonic, which gives the impression of stability. With no intervening notes, the scoring in the trumpets and horns, and the relatively slow rhythms, these tonic and dominant notes attain an awe-inspiring sound not unlike the opening of Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra, heard over the main titles of 2001: A Space Odyssey. On top of that, the triplet rhythm adds a militaristic quality that suggests something powerful. Thus, even in these first few bars, Superman’s heroism, stabilizing presence, and strength are all hinted at.

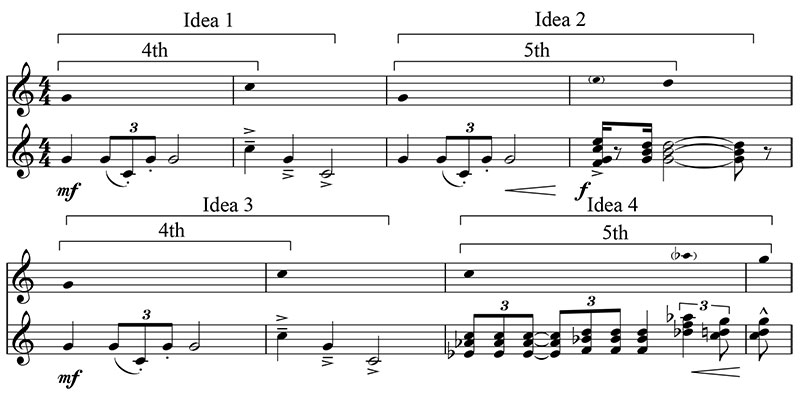

The perfect fifths and fourths in the fanfare don’t just form note-to-note motives, they also permeate the fabric of the fanfare at a more long-range level. The fanfare breaks down into four short pairs of motives – I’ll call each pair an idea:

Each idea contains two notes that stand out more than the others: the very first note and the “goal note” of each idea (shown in the top staff below).

In the first idea, the goal note is the highest note; in the second idea, it’s the last note (though this note is embellished by a note a step higher); the third idea repeats the first, so again it’s the highest note; and in the fourth idea, it’s the last note. Notice that these pairs of prominent notes all delineate either a fourth or fifth.

More importantly, these fourths and fifths form a gradual progression. The second goal note is higher than the first, as though heroically overcoming an obstacle. (The goal note here is embellished by a note that is actually a step higher [shown in parentheses] and physically stands in its place, pushing the goal note off to the next beat.) Notice that the goal note to this second idea is precisely where Williams ramps up the intensity by rising to a loud dynamic, and adding trombones and a cymbal crash to boot. This is also the moment where the music seems to utter the word “Su-per-man!”

Heard as such, the music fuses the characteristics of these first few bars with Superman’s very name. But coming to rest on the dominant chord here, the music, and therefore our hero’s story, sounds unfinished. Will Superman be victorious in the story we are about to hear? The third idea repeats the first idea, and so returns to home base before reaching an even greater height in the fourth idea (again embellished by a higher note), suggesting the ability to surpass mere heroism to achieve superheroism. The fanfare, however, is left tantalizingly unfinished. (More on this later.)

The March

With the arrival of the march at 0:41 in the recording I gave above, we hear in its melody many of the same features of the fanfare: a perfect fourth and fifth at its start, tonic and dominant notes, a triplet rhythm, and trumpet scoring. The same personal traits are therefore suggested in this section as well, but now the accompaniment pounds out chords of great might in the lower parts and, in the upper parts, creates a shimmering effect that suggests something heavenly and god-like. Not to mention that this theme is presented at a loud dynamic in contrast to the start of the fanfare. Clearly, our superhero has arrived and sprung into action.

The melody, however, moves in a new direction:

As before, the dominant, G, is the first prominent note. Twice the melody rises a step to an elated-sounding A, as though celebrating one’s heroic efforts. But it doesn’t stop there. The melody continues to rise by step to B, which desperately wants to move up one more step to C at the top of the scale, but twice this rise is thwarted as the melody drops down instead of moving up. It appears our superhero is up against some great force, and using all his might to try to overcome it. Finally, with the third attempt, the B manages to break through and reach up to the climactic C before falling confidently down an octave on a comforting tonic chord, as if to punctuate the victory. Note that this is essentially the same melodic shape that we saw in the analysis of the Force Theme from Star Wars, which also seemed to depict the struggle of overcoming obstacles, and hence I termed it the “struggle” contour. Significantly, the contour in the march outlines another heroic rising fourth.

The Love Theme

Although the inspiration for the love theme’s melody (at 2:21) is often cited as Richard Strauss’ Tod und Verklärung, the melody can be viewed as having grown out of the melody of the fanfare. Indeed, the two share some striking similarities in structure—notice especially how the second idea of the fanfare is reshaped into the love theme. (I transpose the fanfare below for ease of comparison.)

This similarity not only lends unity to the piece, but subtly suggests two sides of the same personality: the brawny hero and the gentle romantic.

Harmonically, the love theme’s opening is based on a progression that is common in pop love songs: I-II#-IV-I, heard for instance in the Beatles’ “Eight Days a Week”:

In the Superman theme, however, this progression is underpinned by a repeated tonic note (or pedal) in the strings, which continue to play the march’s militaristic rhythm and so suggest an even more overt connection between Superman’s heroic and romantic sides.

In the second half of the love theme at 2:42, the bottom notes of the orchestra fall away and the march’s rhythms yield to an evenly wavering rhythm. Now it is as though Superman’s feet have left the ground and he is gracefully suspended mid-air with his beloved Lois. This theme does, after all, perform double duty as both the love theme and Superman’s flying theme.

The Theme as a Whole

Far from being just a collection of catchy tunes, the structure of the Superman theme as a whole contributes greatly to its emotional power. I have already mentioned the preparatory quality of the opening fanfare, but notice that the first time we hear the fanfare, it doesn’t actually reach an ending. At 0:25, it simply repeats the same penultimate chord instead of moving to a more satisfying tonic chord. This withholding of an appropriately final chord is a powerful tool in the composer’s toolbox as it leaves us craving resolution, forcing us to listen all the more intently in the hopes of achieving it. We’ll return to this point in a moment.

Without a doubt, a significant part of the enormously dramatic impact the Superman theme has on audiences lies in the way a couple of its transitions prepare and build up to the subsequent themes. The first transition occurs just after the opening fanfare at 0:25. At this point, the music is suddenly in a faster tempo and starts to reiterate a new militaristic rhythm at a hushed dynamic (the one mentioned earlier in connection with the love theme). As this rhythm is repeated, the dynamic becomes gradually louder, and more and more of the orchestra joins in. The effect is of something astonishing approaching from a distance. (Is it a bird? Is it a plane?)

Not only that, but the kinds of chords Williams uses in this passage are constructed using fourths (an interval we heard prominently in the fanfare) rather than the more typical chords in thirds (called tertian harmony). These chords in fourths are called quartal harmony and their effect here is twofold. First, as the fourths build up one after the other, almost like a melody, the sound suggests that what approaches is something of great power. Second, when fourths are heard simultaneously in a chord (especially when surrounded by more typical chords in thirds), it sounds as though these quartal chords are actually tertian chords with dissonant notes that need to resolve. Thus, the music attains a powerful sense of forward drive. Furthermore, the final chord of the passage is a quartal chord (or in jazz terms, a “sus” chord) on the dominant, all of which creates a great sense of anticipation, as though something incredible is about to happen.

And incredible it is, as the march theme enters triumphantly, providing the resolution for both the opening fanfare that we had hoped for, and releasing the tension of all the quartal chords into the resounding tertian chord of C major at 0:41.

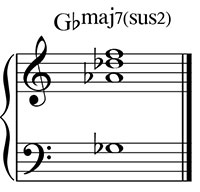

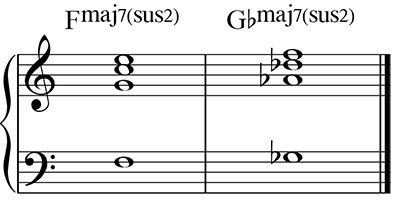

Much the same thing happens after the B section (or “bridge”) of the march at 1:14, where the music attempts to conclude the section three times, the last time leading into another form of quartal chord on G-flat (here marked as a sus chord with added 7th):

This chord in fact has the same structure as the one heard in the fanfare when the music begins to speak the name “Su-per-man”, only now it is transposed up a half-step. Compare the two below:

Both here and in the earlier transition into the march, what is achieved is a heightening of the drama of the Superman theme. So crucial are these linking sections that the theme would lose much of its power were they omitted from the music. To drive this point home, I’ve recomposed these sections of the theme to exclude these passages.

Clearly, the music just isn’t the same without these crucial “build-up” passages.

Conclusion

John Williams’ Superman theme is one of the most iconic in film history as it so effectively captures the film character’s features in musical terms: his unstoppable power, triumphant heroism, stabilizing presence, and capacity for romance. But there is one other aspect of the film that the music captures equally well. As Williams himself said, one of the things he liked about working on the film was that “it was fun and didn’t take itself too seriously.” Surely, the bright, optimistic tone of the theme is a result of this kind of mindset. After all, these were the days before more troubled, tormented superheroes—Batman foremost among them—began to be the norm. Superman fits perfectly into that group of film heroes of the late 70s and early 80s with relatively sunny dispositions like Luke Skywalker and Indiana Jones. Significantly, all three of these heroes have jaunty major-key themes that have become just as iconic as that for Superman, all penned by the inimitable Williams.

Coming soon… Hans Zimmer’s Man of Steel.

Fascinating post. I loved how you revealed the connection between the fanfare and the love theme. I must have listened to that a thousand times and never caught that little piece of genius.

Thank you for this website and the insight that you bring to cinematic music.

Perhaps you could continue analyzing this film with some of the more minor themes like The Destruction of Krypton, The Journey to Earth, Growing Up, Lex Luthor’s theme (The March of the Villains), etc.

Can’t wait for your analysis of Man of Steel. Saw it last week expecting to be disappointed by both the music and the film as a whole. Boy, was I glad to be wrong.

Thanks, Marcus. Great idea about analyzing more of Superman. I’ll put it on my “to do” list (no really, I do keep one!). So it’s just a matter of time before I get to it now.

Good to hear that someone liked Man of Steel. I haven’t yet seen it, so I’m not sure what to expect. But the score I know quite well now, so it will be interesting to see how it fits into the film.

Cheers. 🙂

That was another thing I was wondering about.

What it your modus operandi when analyzing these musical scores?

Do you listen to it first and then watch the movie?

Do you often analyze it on paper as well as in your ears?

Just curious as to your routine for preparing these posts.

My method depends on what it is I’m analyzing. For entire films, like for the James Bond series I just finished, I always watch the whole film then go through it more selectively a second time, making note of what cues come in where. So it’s a lot more work to do those kinds of posts. For new films, it’s harder because I don’t have the luxury of stopping the film and going back over certain parts. In those cases, I prefer to know the music very well before going in so I can try to focus on the story and just know without too much strain what music is being played where. It’s best to see these films twice because of that. For themes like the John Williams series or this latest Superman post, I generally know the theme so well that it’s more a matter of going through the score, listening to certain parts again, and just thinking about it away from the score and recording. I often find that the best ideas come to me that way, when I just sit and think about the theme, because it’s as if my mind is testing out the theme from all sorts of analytical angles, like trying to find the right fit for a puzzle piece.

In grad school, I had a professor who encouraged us theorists not to stop when we found one pattern, but to see if that pattern exists at other places and at other levels (the small, medium, and large scales, for instance). Because with just about all composers, that’s going to be the case – they take an idea an keep repeating it in all sorts of ways. It’s certainly possible to go too far in saying what relates to what, so I really only go for patterns that are strong and, hopefully, convincing.

Although I had noticed the musical intention of the march to draw a picture of Superman’s greatness, I never realized such important details as you wrote about. I’ll certanly pay more attention on the musical structure next time. I mentioned your site in a review of Superman’s films on my blog when I talked about the score, if you don’t mind. Once more, congratulations for the post!

A hug

Thanks for the kind words, Felipe. I’d much appreciate your mentioning my site in your blog. That would be great. Thank you.

Glad you enjoyed the post. 🙂

Dear Mark,

Thank you for yet another of your wonderful film music analyses. I have been following your site in the past months, and found so many interesting things about my favourite composers (Williams, Morricone) that are not available anywhere.

You really should consider writing a history of film music, providing similar analysis of the best film scores, supporting it with sheet music excerpts (this is what other film music history books lack and what makes your site so unique).

Another of my favourites from Morricone is his music for “A few dollars more”, the second part of the dollar trilogy. I hope you can devote some time to that film as well in the future.

Has the Morricone book you mention sheet music excerpts?

Or do you take your sheet music examples from some published anthology, or do you simply transcribe what you hear?

All the best, keep up your wonderful blog,

Karoly

What a terrific post! I just stumbled across your site today, and I’m thankful I did. The Superman March is one of my favorite compositions by John Williams, and while I’ve poured over the score myself more than a few times, your level of insight puts me to shame. Looking forward to combing through the archives here and seeing what new stuff you post!

Awesome post for some of us learning and studying music. Thank you!

I loved your post Mark – many thanks for this fascinating analysis! I have a question: I had also noticed the musical connections between Williams’ Superman theme and the intro of Strauss’ Zarathustra, and had wondered if this was a deliberate reference on Williams’ part. After all, much of the source material for the Strauss piece (Nietzsche’s book) concerns the concept of the Übermensch, often translated as the “Superman”. Do you think it’s plausible that Williams was making a knowing musical allusion to this earlier “Superman” music?

All the best, and keep up the great work.

Ryan

Thanks, Ryan. Yes, now that you mention it, there is a more-than-coincidental similarity between the fanfares for Superman and Zarathustra. Besides the octave motion through the open fifth that begins both themes, the end of the first four-bar phrase, where we hear the orchestra almost speak the word “Su-per-man”, has a stepwise drop to it similar to Zarathustra. But of course, this being Williams, the Superman fanfare is more compact and structured as a symmetrical theme with four bars to each phrase whereas the Strauss is much broader in concept, the space between each note feeling like a mile wide. In Strauss, there’s also the juxtaposition of major and minor chords on the same tonic. The overall effect seems to be one of not just awe, but terror as well. Williams does darken the mood somewhat at the end of his fanfare by dipping into the minor mode, but it sounds heroic rather than terrifying. And the theme’s symmetrical construction and moderate length seems to keep things in check, as though not allowing it to spill over into the frightful-awestruck vein that Strauss taps into. Williams keeps his theme lighter, more buoyant, and ultimately somewhat tongue-in-cheek.

Interesting how very similar basic material can be fashioned in quite different ways even with a strong literary connection to boot. Thanks again for your comment!

What an excellent post – thank you for writing and sharing it. I’ve long been trying to find the most “authentic” and complete solo piano score for playing the full opening theme from the 1978 movie. Most piano sheet music I have found has been “easy to play” type stuff. Would you happen to know if there is a good version out there?

Hello, George. I have looked around too, but always found the same easy-play things you mention. This leads me to believe that a more advanced version has never been published. But that’s not to say you couldn’t make your own. After all, the concert score of the theme is available for purchase, and it’s got all you would need.

Thank you – I’ll take that route. Congrats on a great site.

Thanks for the very detailed and insightful review of this piece. I hope to put it forward to our local orchestra for a performance. Can you tell me how many different instruments it is composed for as I haven’t been able to find the score on the internet. Thanks. David.

Hi David. Thanks for your kind words. The concert version of the Superman March calls for 33 parts. Listing these in traditional order, they are 3/2/3/2 for winds, 4/4/3/1 for brass, 4 for percussion, 1 harp, 1 piano, and 5 string parts.

I liked your comments. I’ve also always thought that the jump from the tonic to the dominant in the “march” theme suggested jumping high (over a tall building?), and was also reminiscent of the theme music from the George Reeves/Superman TV series — which had a similar jump upwards. The same way that Hans Zimmer had to contend with people’s memories of the John Williams score, might John Williams himself have had to contend with people’s memories of the “Superman” TV score? For that matter, the theme from the Fleisher “Superman’ cartoon series starts with the same do-mi-sol motif. The adult audience for the first Christopher Reeve/Superman film had been children watching the TV version. Not so today.

Hi Mark,

5 years late, but I thoroughly enjoyed this break down. I work in the film industry as a Set Lighting Tech in Los Angeles, but have been a life long lover of cinema, and in particular, the rich orchestral themes of John Williams which have inspired me also as a trumpet player. Thought I’d offer a little trivia you may find interesting.

Williams preferred the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) during this time for their impeccable sight-reading skill, and also for the legendary principal trumpet, Maurice Murphy. His sound is unmistakable, and sadly unmatched. Williams referred to his playing as “The voice of a hero”. Much acknowledgment to Eric Tomlinson also, Williams’ sound engineer of the time, for the way he recorded the brass.

Murphy was respected world wide, and can also be heard on the first six Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Batman, Stargate, and many of the Harry Potter Films, just to name a few. Sadly he passed away in 2010, much too early. We are all so lucky the way things went in those magical years when all those movies were being made, and so many talented artists became a part of history.

Hi Craig. Wonderful bit of trivia about Maurice Murphy and his distinctive heroic sound! The trumpet, and Murphy’s sound in particular, is such a central part of Williams’ scores from those decades. I quite like the way Williams’ writing for trumpets in these scores subtly differentiates among different kinds of heroism. In Superman, the doubling of trumpets in octaves gives an impression of super-strength; in Star Wars, the high unison trumpets more generally suggest super-human ability; and in the Raiders March, there are again unison trumpets but now in a lower register, suggesting a more Earth-bound hero prone to adventure. Such great scores in so many ways!

And don’t worry about the “late” comment. I’m glad to hear about these things at any time at all!

Nice

What ensemble is used in this piece of music

Hi Mark, thank you for this great work. I have a question for you. Do you know if there are different official orchestra arrangements for this theme? I ask because I have heard that in the 1978 soundtrack, in a slow section (1:30 from the video you shared), there are no trumpets, but when I listen to live concerts, I do hear trumpets responding to the strings. The same thing at the end, at 4:02, when different sections play a similar phrase, the trumpets come at the third repetition of the phrase only, but in other concerts they play this phrase 2 times, after the trombones I think.

So why this different arrangements? Why they do not stick to the original. I can not imaging making such changes to classical music in an orchestra setting.

Here is a link where you can see, John Williams conducting, and with a different arrangement for those two places.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fl2JtQ4qNzw

(1.35 and 4:17 in this video)

Or maybe I am wrong and they both play identical and its just a recording quality? Please be kind to comment, thanks!

Hi Xavi,

Great question! There seems to be only one version of the concert score for this piece. I’ve listened to the original recording many times and in four different masterings – the original OST (YouTube), the Rhino release (2000), the FSM Blue Box (2007), and the La-La Land release (2019). The trumpets are there in this recording, they’re just hard to hear in those places, either due to the way the microphones were placed or the way the recording was mixed. You can just barely make out the buzzy, brassy sound of the trumpets. But only just!

Thanks a lot Mark!!