“Cheyenne’s theme” from Once Upon a Time in the West is another example of Ennio Morricone’s economical use of melodic and harmonic materials, and unusual choice of instrumentation that help bestow his music with a very distinctive sound. The following film music analysis will demonstrate how the theme incorporates some of the same ideas from Jill’s theme and includes some others that are commonly found in Morricone’s film scores.

Within the film, Cheyenne’s theme is heard in two forms. The first sounds when he is introduced as he enters a tavern. This form of the theme is fairly fast-paced, eerie, and tension-filled, appropriate expressions for a character who has, thus far, only been shown to be a dangerous man who is skilled with a gun. All other instances of the theme make use of its second form, a more moderately-paced version that accompanies Cheyenne in various other situations. It is this form of the theme that is analyzed below.

Melody

Cheyenne’s theme is structured as an ABA form in which the final B and A sections are reiterated twice. Below is the entire theme along with the timestamp for each of its sections:

0:05 – A, 0:25 – B, 0:47 – Return of A, 1:06 – B, 1:28 – Return of A, 1:47 – B, 2:09 – Return of A

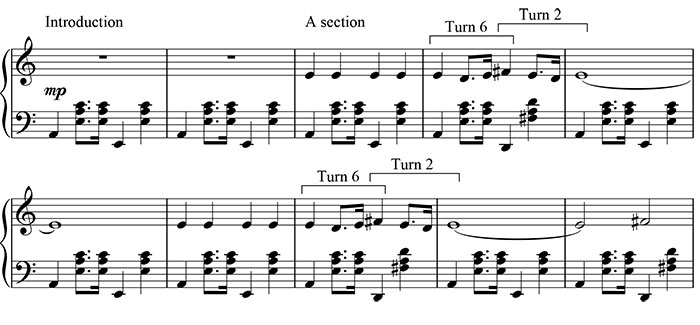

After an introduction announcing the theme’s sauntering accompaniment figure, the opening A section enters, comprising two identical four-bar phrases. These phrases state a rhythmic motive that, with only slight variations, is the basis of each phrase in the theme, demonstrating one of the theme’s many musical economies.

Recall Morricone’s claim that, in the early Sergio Leone films, he would sometimes write “a theme of intervals”. As we saw with Jill’s theme, this statement holds true in the theme’s prominent use of the interval of the sixth. Cheyenne’s theme may not seem to highlight any particular interval since it is based almost entirely on repeated notes. But repeated notes are themselves a type of interval – the unison. Hence, Morricone is employing much the same compositional technique, saturating the theme with a single type of interval. In this case, the combination of the unisons and moderate tempo endows the theme with a relaxed character that befits the generally less intense role Cheyenne plays in the film (frequently as a comic relief).

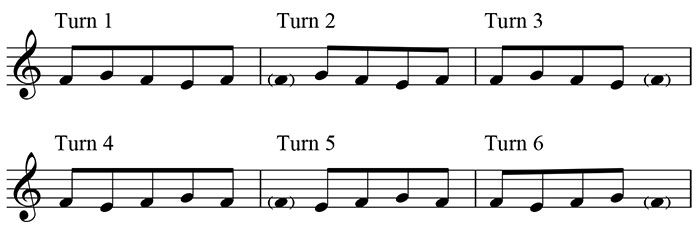

In terms of melodic devices, Morricone once again draws on the figure of the turn. In the last analysis, we saw that there are six types of turn depending on whether the figure is inverted or omits its first or last note:

Cheyenne’s theme integrates two turn figures in its opening phrase that overlap with one another:

And the B section concludes with one of the abbreviated forms, strengthening its already close melodic relationship to the A section through the many repeated notes:

These turn figures not only create interest in the melodic line through their contrast from the unison intervals, but they also sculpt the theme into something distinctly Morriconean.

Harmony

Keys and Scales

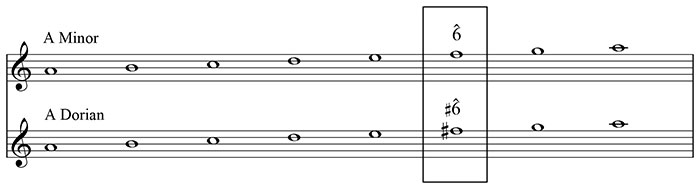

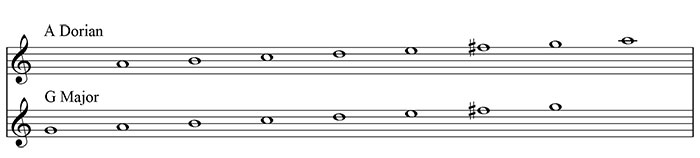

The opening A section of Cheyenne’s theme is composed of a repeated three-chord progression: A minor, D major, and again A minor. Had this theme been set in the key of A minor, the second chord would have been a D minor chord. But the melody’s turn first figure rises up to F# instead creates a D major chord and renders the theme’s underlying scale a Dorian mode on A, which is like minor but with a raised sixth degree:

This use of a major chord where one would normally expect a minor allows the phrase to alternate between “negative” minor and “positive” major chords, suggesting the moral ambiguity of Cheyenne’s character: on the one hand, he is an outlaw who at the start of the film kills several police officers in order to escape his convoy and gain freedom as a fugitive. On the other hand, he aids Jill in her quest to ward off the killer Frank and prevent her newly inherited property from falling into the clutches of the land tycoon Morton. In addition to bearing a resemblance to the plagal thirds progression of Jill’s theme (I-vi-IV-I), the Dorian plagal progressions between major IV and i are also a key ingredient of Morricone’s main themes to Leone’s three earlier westerns, where moral ambiguity is a prominent aspect of the main character, Clint Eastwood’s “man with no name”. Listen, for instance, to the first three chords of the main theme to The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, a clear example of a i-IV-i progression, and note especially the major chord sandwiched between two minor chords:

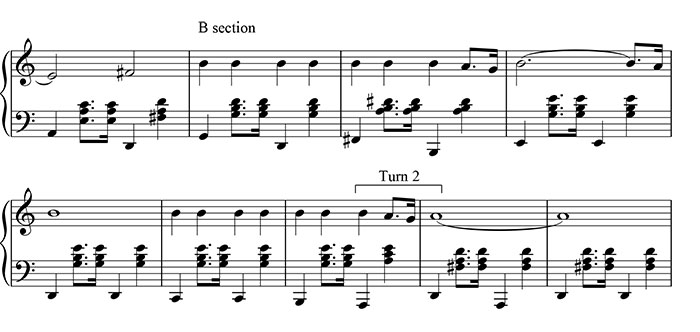

The B section begins with a pickup that uses another D major chord, now as the dominant of G major, into which key the music pivots and remains for the entire section. Taken together, then, the A and B sections take the idea of minor-major contrast that we hear in the A section’s plagal progressions and apply it to entire key areas. In terms of expression, the major-key foundation of the B section adds a certain poignancy to the theme as it seems to suggest something of Cheyenne’s softer, altruistic side whereas the minor-chord emphasis of the A section is suggestive of his harder, more rugged exterior. Also, the A Dorian mode of the A section and the G major key of the B section are actually two forms of the same musical scale, just beginning on different notes:

Hence, in addition to their obvious similarities in melody, accompaniment, and scoring, the A and B sections’ use of the same basic scale implies that the contrasting emotional expressions are two sides of a single personality.

Harmonic Progression

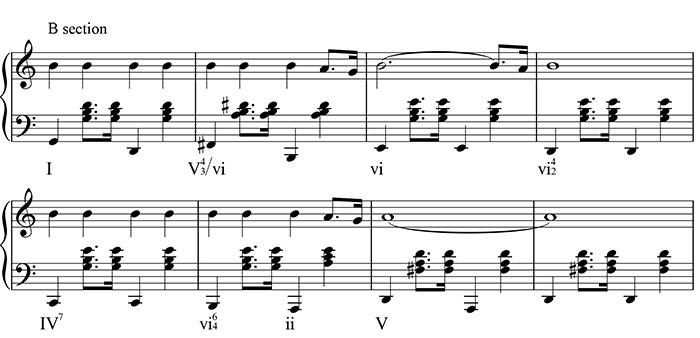

The B section is based on a single harmonic progression of eight chords in G major:

Notice that the progression passes through the chords of I, vi, IV, and ii, all of which are in their strongest form by being in root position. In other words, these chords stand out more than the others by sounding more stable, like stations along a train’s journey. In between each of these chords is a less stable, or “passing”, chord that sounds like it needs to resolve. Thus, the progression sounds like a filled-in form of I-vi-IV-ii, which is known as a descending thirds progression. Recall that the A section of Jill’s theme was based on the plagal thirds progression, I-vi-IV-I, which was also filled in with passing chords and a stepwise bass line. The two progressions are therefore close relatives of one another and not only create a subtle link between the themes for Jill and Cheyenne, but also demonstrate another way in which Morricone draws on a relatively small group of musical devices to define his very distinctive style.

The final chord in this progression, V in G major, produces an unfinished type of cadence called a half cadence, which here closes off the entire B section. But notice that this chord is another D major chord, this time moving directly into the return of the A section, which begins with the familiar A minor chord that starts the theme. Just as the D major chord brought us into the B section, Morricone now employs it again to take us back to the A section. With this move back into the A section, we realize that the D major chord also functions as the major IV chord in the A Dorian mode on which the A section is based. Thus, not only is the chord an appropriate choice to set up a sense of expectation due to its unfinished quality in either the G major of the B section or the A Dorian of the A section, but it also leads us back into the i-IV-i plagal progressions of the A section without introducing any new harmonies. This is Morricone’s musical economy at its finest.

Harmonically and melodically, the return of A section is a literal repeat of the initial A section, but with one important change in its final iteration. Just before the last chord of the section, the music breaks off for a full bar of rest. The need for resolution to that last chord creates a “pregnant” pause that brings with it a feeling of great anticipation, as though we are holding our breath, waiting for something to happen. In the film, this pause is coordinated with several of Cheyenne’s actions, including delivering a punchline, creating a moment of suspense, or even keeling over in death. And sounding after two identical iterations of the B and return of A sections, Morricone’s pause brings an unexpected reprieve from the theme’s phrase structure – a departure from his musical economy becomes an effective way of closing the theme.

Orchestration

As we saw with the analysis of Jill’s theme, Morricone himself has stated that

“I have always believed that the inventive use of tone color is one of a film composer’s most important means of expression.”

The unusual but skilfully blended orchestration of Cheyenne’s theme is an inspired testament to Morricone’s words. Right from the opening accompaniment figure, a double bass plucks out the “moseying” bass notes, and a wood block provides the clip-clop sound imitating a horse’s hooves. The strummed chords are played by an acoustic guitar doubled by a harp that is quickly muted by the hand (known as étouffée technique), and the theme’s melody is announced in the unusual combination of banjo and honky-tonk piano. Upon reaching the return of A section, however, Morricone adds his favoured sound of a male whistler (Alessandro Alessandroni), hence distinguishing the initial A from its return by minimal means. While the guitar, wood block, and whistling leave no doubt in our mind that this a cowboy theme, the overall synthesis of sounds produces a unique effect that bears the mark of a distinctly Morriconean orchestration.

Conclusion

Like Jill’s theme, Cheyenne’s theme is a good example of both Morricone’s adherence to a small musical palette of melody, harmony, and phrase structure, as well as his flair for highly original orchestrations. Its melody uses a single rhythmic motive throughout the theme, draws on the turn figure, and is constructed largely of unisons (repeated notes) that demonstrate the composer’s technique of writing “a theme of intervals”. Harmonically, the theme incorporates plagal progressions, minor-major contrast in both its chords and keys, the descending thirds progression, and two forms of exactly the same scale. And the orchestration almost completely eschews instruments of standard orchestral fare in favour of a more distinctive, and distinctively cowboy-like, combination. Taken as a whole, these many elements fuse together and coalesce into a highly recognizable style that could only have emerged from the pen of Ennio Morricone.

Coming soon… Morricone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (Part 3 of 3): Frank/Harmonica’s theme.

So, in a sense this is somewhat ‘spare’ music – like “The Good, The Bad…” – which suits the film’s sparse landscape and somehat isolated setting.

This is another excellent analysis; thank you. These films have never been favourites of mine – I’ve often wondered why an Italian would want to duplicate a genre which Americans ‘own’ as particular to their culture and which shaped the American national consciousness (eg. gun ownership). Having said that, westerns are finally costumed morality plays and these films of Sergio Leonie demonstrated skill and artistry. Ennio Morricone played a huge part in that.

His music has that haunting quality to suit the landscape, but I also feel there is a parodic quality to this score, especially noticeable in the ‘honky tonk’ sections. I never liked to hear whistling in a film score, though, and I wonder whether Morricone was being deeply ironic here – suggesting a laid-back mindset in the outback when the truth is exactly the opposite. (I’ve been involved in a discussion elsewhere about irony in music.)