This year’s passing of legendary film composer Ennio Morricone prompted me to reflect on what makes his film music of such broad appeal. Morricone himself offered a very fitting answer in a recent book of conversations from 2013–2015 with Alessandro De Rosa titled In His Own Words, in which De Rosa asks the composer this very question about his music for Sergio Leone’s films:

I think it is due to their sound, which is not by chance the same sort of aspect rock bands research: an identifiable sonorous timbre, a sound. Moreover, I think that a great part is also due to the singability of the melodic lines and their harmonies: invariably in every piece there are very easy chord sequences. Lastly, I am certain that Sergio’s films spoke to many generations precisely because he was an innovative filmmaker who intentionally left space for the music to be listened to.

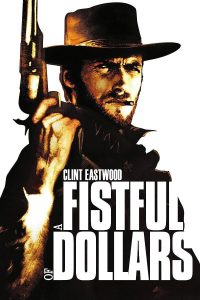

No doubt, Morricone is right on all these points. And to this list we could add the virtuosity of his performers, for example in A Fistful of Dollars, the trumpet player Michele Lacerenza and the whistler Alessandro Alessandroni. But there is another key point he does not mention that I believe is crucial to these scores’ success: their integration with the core ideas of each film, in other words, the way in which the main ideas of each film are enhanced through Morricone’s music. This three-post series will examine just how these three scores of Morricone achieve this integration. Moreover, as discussed in De Rosa’s book, Morricone’s scores to the Dollars films reveal a fascinating evolution in which this integration of music and film becomes increasingly tighter across the trilogy. We begin with the film that started it all, A Fistful of Dollars, and hone in on its two prominent themes: the main theme and the duel theme.

The Main Theme

From the mid to late 1950s and up to A Fistful of Dollars in 1964, Morricone worked for Italian radio broadcaster RAI arranging popular-style music, and for RCA creating popular-song arrangements. Through this experience, Morricone always experimented quite a bit, saying “I tried to vary as much as I could to break the rules of the craft and avoid boredom.”[efn_note]De Rosa, In His Own Words, 10.[/efn_note]

The main theme of A Fistful of Dollars is used mainly for the film’s protagonist, Clint Eastwood’s famous “man with no name” (though some call him “Joe” in this film). And the theme isn’t simply influenced by Morricone’s popular-scoring background, indeed it is a lightly adapted form of his arrangement of “Pastures of Plenty” a song for Californian singer Peter Tevis. Listen to a bit of the arrangement below:

Morricone’s arrangement of this song completely transforms the original setting by the song’s composer, singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie. Listen to a few seconds here:

Of his arrangement of the song for Tevis, Morricone says,

my thought was to put listeners in touch with the faraway pastures described by Guthrie; this is why I inserted the timbres of the whip and the [clay] whistle. The bells were intended to suggest the countryman who longs for the life in the city, away from his daily routine.

This kind of musical imagery is a perfect fit for Eastwood’s Joe, a lone gunfighter who rides from town to town through the western frontier. But in arranging this music for the film, Morricone makes a very important change: the sung melody is replaced with a new melody that is whistled. As De Rosa states in his discussion with Morricone on Fistful, “among the timbres you used, the whistle is perhaps the most primitive but also the most intimate one: in a world in which life is not worth much, to whistle at night by the fire with pride and a bit of boldness is the only way to keep loneliness away.”[efn_note]De Rosa, In His Own Words, 27[/efn_note]

And since the whistling is used for the theme’s most prominent part—the melody—it focuses our attention on this appropriate blend of the primitive (everyone killing each other), the intimate (developing sympathy for the protagonist), the bold (Joe performing many such actions throughout the film), and the lonely (he is always forced to relinquish any friendships he forms, because either he or his friends must flee to avoid danger). So even though this theme is essentially Morricone’s arrangement for Tevis imported into Leone’s film, he nevertheless had the acumen to see how appropriate this choice of music was. And it was the result of careful thought on Morricone’s part, as he made clear in a conversation with musicologist Sergio Miceli:

I have always believed that the inventive use of tone color is one of a film composer’s most important means of expression. Under the influence of this way of thinking, I began to experiment with music made expressly for the stage, but above all for the protagonist in Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars) (1964) and all Leone’s other films. The western helped me, because the genre, at least as Leone intended it, is picaresque, exaggerated, excessive, playful, dramatic, entertaining, and caustic.

The caricatured figure of the protagonist is delightfully forced by the director. … In the presence of this kind of direction, especially a director used to excellent results, it was necessary for me to use unusual sounds that would be able to equal these excesses. … Everything, including the soundtrack, had to appear to be much more than it really was. Thus, therefore, I called for bells, whip, whistling, anvil, clay whistle, voices, and … so many other things.[efn_note]Ennio Morricone and Sergio Miceli, Composing for the Cinema: The Theory and Praxis of Music in Film, 167.[/efn_note]

Listen to the full theme here:

The Duel Theme

For the music that accompanied the film’s climactic duel between Joe and the fearsome members of the Rojo gang, Sergio Leone had initially wanted to use the piece he had used in the temp track, Dimitri Tiomkin’s “Degüello” from Rio Bravo (1959). Morricone describes his own response:

I told him, “if you use it, I quit.” And I did—in 1963, a year in which I was penniless! Shortly after, Leone stepped back and allowed me more freedom, although he was annoyed. “Ennio, I ain’t asking you to imitate it, just come up with somethin’ similar…”

What was he trying to say by that? That I had to stick to what that scene meant to him: a death dance fitting a southern Texas atmosphere, where, according to Sergio, the tradition of Mexico and the United States blended.

To respond to this compromise I took a lullaby I had composed years before for Eugene O’Neill’s Plays of the Sea and sneaked it in without saying anything to him. I rearranged it in a more incisive way so as to extol the mounting solemnity of the trumpet leading the viewers into the duel. I played it for him at the piano, and I saw he was convinced.

“It’s perfect, it’s perfect….But you must make it sound similar to ‘Degüello.’”

As we will hear shortly, Tiomkin’s and Morricone’s cues have a similar sound in terms of melody, accompaniment, and orchestration. So one may ask why Morricone kicked up such a fuss if his theme apparently doesn’t sound so different from Tiomkin’s. In part, it was due to Morricone’s personal integrity and not wanting to mimic another composer’s cue. But this integrity combined with Leone’s insistence was a recipe for greatness. If one listens to both cues all the way through, as we will in a moment, it becomes clear that Morricone did not simply imitate Tiomkin with minor changes, he created a cue that I argue is superior to Tiomkin’s for the final duel because of the dramatic arc of the theme as a whole.

To demonstrate this point, I have created a video replacing Morricone’s duel music with Tiomkin’s “Degüello” as Leone had initially wanted. As we will see, both Tiomkin’s and Morricone’s cues fall into three main sections, which correspond with the scene itself since it unfolds into three non-verbal parts before the dialogue begins. These parts are:

- Smoke and Mystery Man – The explosion Joe sets off behind the town and the resulting smoke conceals his identity, preparing for a dramatic entrance as the smoke blows away.

- Mystery Man Revealed – The Rojos realize that the mystery man is Joe and their looks to him and each other betray their uneasy reactions to him.

- Preparing for Gunfight – Joe approaches the Rojos and they take their positions in the town square for a gunfight.

In terms of timing, Tiomkin’s cue actually fits quite well, with the three musical sections being about the same length as the three narrative parts. But what is sorely missing here is a sense of drama. Tiomkin’s cue falls into a large ABA pattern, but it lacks any sense of climax as it doesn’t intensify through melody, harmony, orchestration, etc. It’s a fine piece of music with an unmistakably Mexican flavor, but for this particular scene, as the gunfighters prepare for their final confrontation, there really ought to be some sort of intensification through the music, especially since there is no dialogue and the music is the focus of attention. Here is the clip rescored with Tiomkin’s music:

As I mentioned before, Morricone’s cue for the scene has three sections that correspond with the scene’s three parts. But the cue instead falls into a structure of AA’B (+ short coda), where the “prime” symbol (which looks like an apostrophe) indicates a variation of the original A section. The short coda is based on the A section, but it is much shorter than A or B, so is more of an appendage to the cue than a section in its own right.

What becomes clear in Morricone’s cue is an overarching dramatic shape that infuses the scene with a greater intensity than Tiomkin’s could have, and provides the film with a fitting sense of culmination as Joe faces the deadly Rojo gang alone.

The first A section announces the theme at a low level of intensity, appropriately enough for the clouds of smoke surrounding the mystery man. The A’ section increases the intensity subtly at first by adding a male choir then more prominently in its latter portion by adding higher notes in the accompaniment (listen for the female choir and high violins), by becoming louder through a crescendo, and by stretching out a dominant chord over several bars that heightens the need for resolution. This intensification tells us that, with the mystery man now revealed, worry is mounting among the Rojos that perhaps what Joe wants with them is a duel.

The B section arrives just as Joe begins to approach the Rojos, confirming that a gunfight is indeed what he has come for. Morricone’s music here renders this confirmation a climax of the scene and dramatically emphasizes the showdown that is about to follow. Not only is this the loudest part of the entire cue, but it is also where the trumpet melody and full choir are the highest, and where the long dominant chord of the A’ section finally resolves to the home key tonic. There is no mistaking that this is a central moment in the film, as is clearly intended by Leone with the long wordless lead-up to the battle.

The coda based on A serves to close out the cue on a softer note, so as not to suggest that a fatal shot will be fired immediately after. Morricone’s music simply points to the entire gunfight (beginning with the men taking their positions in the town square) as the climactic event in the film, and it does so in an entirely musical way that coordinates perfectly with the three narrative parts of the sequence. While Tiomkin’s music also divides neatly among these three parts, its structure does not highlight the ensuing gunfight as a pivotal event since dramatically it remains more or less the same throughout. This is why I say that Morricone’s solution is by far the superior one.

Now watch the scene again with Morricone’s music:

Conclusion

As we have seen, the two themes in A Fistful of Dollars are very well integrated into the core ideas of the film. It may therefore be surprising to learn that Morricone himself held the score in very low esteem, saying “to be frank, despite the consensus that it received, I still think that that music was among the worst I have ever composed for a movie.”[efn_note]De Rosa, In His Own Words, 27[/efn_note] Perhaps Morricone was unhappy with what he perceived as a lack of refinement in the score since he was to take this style to even greater heights in the next two films of the trilogy (as we will see!). Even so, most of the elements that we associate with Morricone’s Leone-western style are already present in the score for Fistful, and I hope to have shown in part how they are nevertheless a brilliant solution to the needs of the film.

Coming soon… For a Few Dollars More

Fine commentary, thank you. Can you discern from Fistfull’s opening titles theme what the periodic chant is? It sounds to me like “we can work” or something similar. Please advise, and thanks.

Hi Mark. Morricone explains in In His Own Words that, after playing “Pastures of Plenty” for Leone,

Remerciements Mark 🙂

… Mark…