It’s a question that many of us wonder about how film music is made, especially given that film composers generally work to tight deadlines and can’t afford to wait around for a moment of divine inspiration. So how is it, then, that these high pressure conditions have managed to produce so many highly effective film scores?

Most composers begin their work in postproduction after the film has been shot and a rough cut edited together. The visuals of the film often give them the inspiration they need to write the score. Hugo Friedhofer, who worked as an orchestrator for Erich Korngold, said that Korngold’s compositional process involved viewing the film, going home and inventing some themes, then returning to watch the film again, this time improvising on his themes on an upright piano in the projection room while the film was running. From there, it was a matter of refining the music before finally recording it.

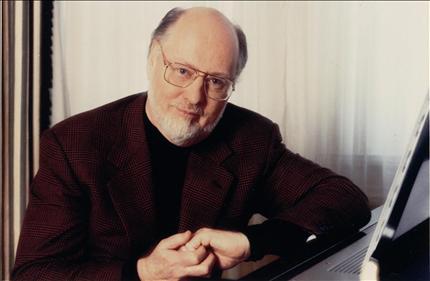

John Williams, who worked as a jazz pianist for Hollywood films in his early years, likewise relies on improvisation at the piano for his film scores, albeit in a different way. After viewing the film, he improvises at the piano and writes about three minutes of music a day for full orchestra in a shorthand form, all with pencil and paper.

By contrast, for a composer like Danny Elfman, Janet Halfyard mentions that “the starting point—particularly when he is working with a director he has worked with before, such as Burton or Raimi—has been to visit the set during production, where he starts to get a feel for the visual identity or ‘tone’ of the film: this is something he has been doing on Burton’s films since Beetlejuice.”

Although like most composers Alex North, who scored such classics as A Streetcar Named Desire, would begin scoring in postproduction, his inspiration for the music generally came from the script, before the film had even been shot. This is not so surprising given North’s experience in the theatre, scoring music for plays, which are based largely on the written word.

Similarly, James Newton Howard begins his work by writing a 10-20 minute suite of music based on his impression of the script. Although the music may change drastically from here, many of the ideas in this suite usually end up in the final cut of the film.

On the other hand, pioneering film composer Max Steiner found composing from scripts to be frustrating because of the amount of change they would undergo in the final film. Consequently, Steiner later stated flatly that “I never write from a script. I run a mile every time I see one.” As with most composers, Steiner preferred to begin his work in postproduction with a rough cut of the film.

In the case of Ennio Morricone’s score to Once Upon a Time in the West, director Sergio Leone, unusually, asked Morricone to write and record the music before the film was shot. The recorded music was then played on set with loudspeakers to give the actors a sense of the highly emotional feel of the film.

Such conditions, however, are extremely rare and in most cases not even desirable since the director can change his or her mind and ask for entirely new music after the composer has already done the work. This was the case with Maurice Jarre’s score for The Mosquito Coast, which was recorded and used on set but later discarded because director Peter Weir’s conception of the film had changed during filming. Jarre then had to write a brand new score for the film.

Sometimes a small detail of a film’s sound world seems to provide the composer with inspiration. To mention Morricone once again, his main title music for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly begins with a wail—a rapid oscillation between two notes a perfect fourth apart. This motive becomes a prominent part of the score as it is used as the theme for all three of the main characters in the film (though with different orchestrations). Morricone himself describes the idea as the sound of a coyote. And if one watches the opening scene of the film, the first prominent sound one hears is the howl of a coyote that is uncannily like Morricone’s wailing motive heard in the main title.

Finally, some composers work on a more intuitive level, viewing the rough cut of the film then composing music that seems to fit the general emotional tone of each scene, as did Bernard Herrmann. Herrmann rarely composed “themes” in the traditional sense of using leitmotifs for certain characters and instead believed that one of film music’s primary functions was to “seek out and intensify the inner thoughts of the characters.”

Hey. Great Website I love it.

I have a question : is there some place that i can learn these music characteristics like a theme that is Dark or Mystic or Happy. (I understand the Major Minor feelings) and are these Tonal music ? or Modal and Atonal ?

I’m a classical composer myself but in classic we don’t have these feelings or I don’t know about them.

This is Spectral and Minimal music combined and orchestrated if i’m correct.

My goal is to achieve high places in Classical and Film music but I don’t know where to read about Film music.

Hi Soroush, and thanks for your kind words about the site. About writing with certain emotions in mind, that’s a very hard question to answer because there are so many ways to write a “dark” theme, or “mystic” theme, or “happy” theme. There are certainly some common features found in many of these sorts of themes, though. Dark themes tend to use a lot of low notes, and the harmony is often minor chords, atonal chords, or other dissonant chords, and the rhythm is usually fairly calm. Happy themes, on the other hand, are quite the opposite, with the melody usually in a mid or high register, lots of major chords, and very active rhythms. But these are only tendencies and are not rules by any means.

There isn’t really one book I can recommend that explains how film music expresses certain emotions. The best thing I can suggest is just to listen to a lot of themes that sound “happy” or “mystic” or whatever feeling you’re looking for, and try to hear some common techniques among them. Then again, if you were looking for how a certain aspect of music might express a certain emotion (like harmony, or instrumentation, or melody), there actually are bits and pieces in the literature that discuss these sorts of things, but it depends which aspect you want to study. There is, for example, a great article by Frank Lehman about how cadences in film music create certain emotions. I always learn something every time I revisit it.

Wow Thanks man. Thanks for the help. I’m really learning from you. You’re great <3

Are there avenues to get one’s music to film, other than a music supervisor, publishing?

Hi George. I’m afraid I can’t be of much help that way because it’s not my expertise. Besides moving to a filmmaking center like LA or New York, you might try offering your work to student filmmakers at a film school since they always need music. You’d probably be working for free but at least it’s somewhere to start.