When director Christopher Nolan first approached his regular composer, Hans Zimmer, to write the score for Interstellar, he wanted to avoid the clichés associated with the science-fiction genre and “engage Hans in a very pure creative process.” To do this, Nolan sent Zimmer a single typewritten page with snippets of dialogue Nolan had written for the film along with some general ideas that, he said, described the relationship between a father and his son. (Only later was Zimmer told the son was actually a daughter, probably to avoid film-music stereotypes of femininity.) The genre and scale of the film were deliberately withheld from Zimmer and he was given one day to write his initial ideas and present them to Nolan. These ideas, which can be sampled below, certainly suggest a more intimate and emotional film than comes to mind when one thinks of the sci-fi genre.

But the score for Interstellar is also notable for its prominent use of the pipe organ, an instrument that, in film, is normally reserved for scenes involving religion in some way. As Nolan explains,

“I also made the case very strongly for some feeling of religiosity to [Interstellar], even though the film isn’t religious, but that the organ, the architectural cathedrals and all those, they represent mankind’s attempt to portray the mystical or the metaphysical, what’s beyond us, beyond the realm of the everyday.”

Thus, while the score’s use of the organ is not associated with religion, it does conjure up similar feelings of striving for levels of existence that lie outside of everyday experience (a narrative theme that Interstellar shares with one of its obvious influences, 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film in which the organ can also be clearly heard, for example, at the end of the main title cue with Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra.)

In its structure, however, Zimmer’s Interstellar is like many of his other scores, relying on a few thematic ideas that are applied in a non-traditional way. That is, rather than simply being associated with a certain character or group of characters, Zimmer’s themes tend to emphasize the emotions a particular character or group is feeling at various points in the film. The following film music analysis explores these broad associations in the film’s four most prominent themes.

Murph and Cooper

This theme is generally heard when the focus is on the relationship between Murph and her father Cooper. Its first appearance is in fact with the studio logos before the start of the film proper, suggesting the importance of the theme’s association to the narrative. (Indeed, Murph and Cooper are the first two characters to interact in the film.)

Perhaps the most obvious signal of the theme’s association occurs in the emotional scene when Cooper, a former NASA pilot, says his goodbyes to the child Murph before leaving his family to join the interstellar mission to save humanity. Murph begs Cooper to stay, telling him that even the mysterious “ghost” that inhabits her room seems to be saying the very same thing. The theme is also heard when, after waking from his cryogenic sleep on the Endurance spacecraft, Cooper hears that Murph refused to make a video message to send him, and occurs once more when Cooper is told that Murph is on her way to see him again after learning of his return.

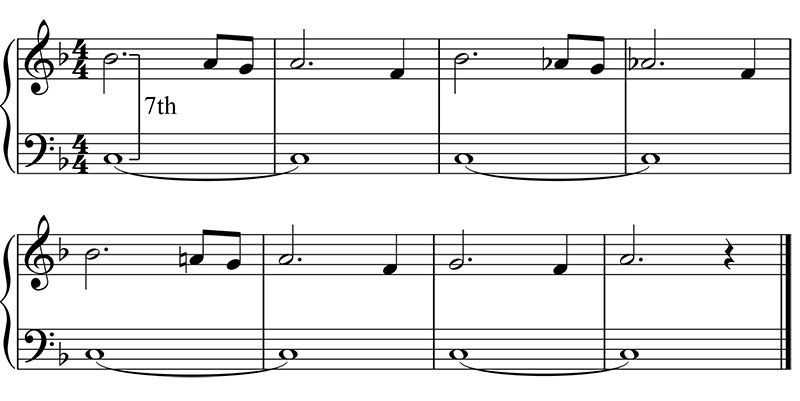

Musically, the theme’s melody begins with a long note that lies a seventh above the bass, creating an interval that has a feeling of vastness to it and thus suggests the great distance that will long separate Cooper from Murph. (Recall that this same interval was also used in last year’s blockbuster space-themed film, Gravity, as a suggestion of the vastness of space.)

More subtly, the theme is supported by a sustained bass note, or pedal point, that sounds the fifth, or dominant, note of the scale. Since dominant bass notes create an expectation that they will, at some point, resolve to the first note of the scale, or tonic, to sustain a dominant pedal at length as this theme does gives an impression of a prolonged avoidance of resolution. Indeed, given the enormous length of time that elapses during Cooper’s absence, this is an entirely appropriate sentiment.

The theme also implies both the loving and hurtful aspects that comprise Murph and Cooper’s relationship through its juxtaposition of major and minor. While the theme begins in the major mode, suggesting the loving aspects on which the relationship is built, it is immediately followed by a statement in the minor mode, implying the grudge Murph holds against Cooper for feeling abandoned by her father. Hear the theme below from 0:41 to 1:45:

One other place the theme recurs is the scene where Cooper detaches his shuttle from Endurance to give it the “push” it needs to escape the black hole’s gravitational pull. Though Murphy is neither onscreen nor even mentioned here, Cooper’s decision to detach is a crucial one that leads to him making cross-dimensional connections with Murph that are pivotal to the film’s narrative. The Murph and Cooper theme is thus played in grandiose style to mark the importance of this decision, as heard below (from 3:48 to 4:53):

Love / Action

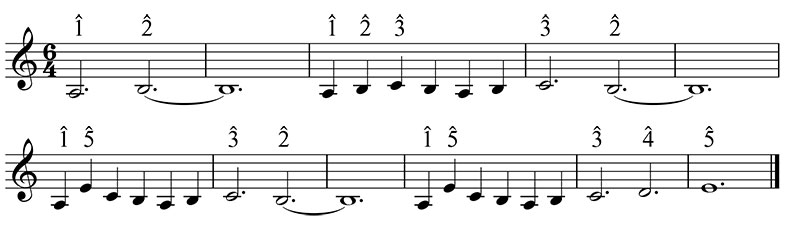

This might be considered the score’s main theme as it embodies the kinds of emotional ideas that are suggested by the description of Nolan’s one-page letter to Zimmer. As a main theme, it is not confined to a single association but rather has two disparate uses, each of which is reinforced by its orchestration. It also is divided into two components: a melody based on a repeating two-note motive (played on the organ), and a repeating harmonic progression with a bass that rises by two steps then falls by one.

It first enters when Cooper and his two children (Murph and his son Tom) chase down an automated plane-like drone flying over the farm in order to capture its solar cells. This is one of the only times in the film that we see the family united in a common action, and reasonably happy to be so. The love comes more into focus when Cooper, who is viewing messages from the last twenty-three years on Earth, is moved by the major events to have occurred in his family and sobs uncontrollably. We hear the theme with this association of love again when Cooper makes the cross-dimensional connections with Murph, which are guided by the love between the two characters. One final appearance of the theme occurs when Murph is happy to see Cooper again nearly a century after he left Earth. Common to all these forms of the theme is the melody composed of two-note figures, heard below from 0:09:

In the above situations, the theme occurs in a lightly orchestrated form, with the delicate melody played on the organ. At other times, the theme acquires a “bigger” effect by omitting the melody and adding a more massive orchestration, a sound that is associated with scenes of heavy action. The two instances this occurs are on the first planet the interstellar crew visits, where they meet gigantic tidal waves, and when Cooper and Brand are re-docking with Endurance after it is set spinning out of control. Below is this version of the theme from 2:35:

Though the theme’s two uses are opposing in meaning, its musical structure helps to understand why it works in both cases. The theme is set in a minor mode and is supported by a bass line that progresses from scale degree 6, up to 7, and up once more to 1. In minor keys, scale degree 6 typically falls down to 5 since the latter exerts a kind of gravitational pull that attracts 6 towards it. The pull is especially strong in minor since the distance between 6 and 5 is a mere half step, or semitone. Listen, for example, to a version of the minor-mode Frank/Harmonica theme from Ennio Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West, paying particular attention to the way that scale degree 6 in the bass seems to be “pulled” down to 5 at 5:04 (start from 4:50):

As with gravity in the physical world, breaking free of a gravitational pull requires a good deal of energy, and with the bass motion from 6 to 7 (which is two half steps, or one whole step), there is a sense that a substantial amount of energy is being exerted, an energy that we could even say continues in the rise from 7 up to 1 (another whole step).

This sense of struggling to escape some great obstacle is present in both the “love” and “action” forms of the theme. In the former, this occurs emotionally by demonstrating that love, although challenged, transcends vast expanses of space and time. In the latter, the obstacle is clearly physical, be it a tidal wave or a spiralling spacecraft.

Wonder

Interstellar is a film that tackles such ambitious ideas as space travel, wormholes, black holes, and Einsteinian time dilation. Given this focus on scientific wonders, it is no surprise that one of the film’s musical themes—which I simply call the Wonder theme—expresses a sense of fascination with one’s surroundings. The theme enters at several points in the film: when Cooper’s farm machines “go haywire” and start heading north instead of maintaining the crops, when Cooper observes what appears to be a message in dust written by an unknown being, when Cooper and the crew first enter Endurance, when they reach the distant galaxy through the wormhole, and when Cooper and Mann explore one of the potentially-habitable planets. Hear the theme in the cue below:

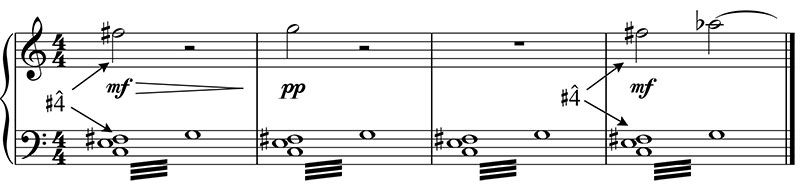

The most prominent features of this theme are its sustained, shimmering accompaniment and the continual recurrences of a single melodic pitch. The accompaniment sustains a major chord along with a dissonance created by the raised 4 of the scale. As I have noted before, this scale degree (whether in major or minor) has long been associated with the mysterious or inscrutable, other examples being Morricone’s Frank/Harmonica theme, Hedwig’s theme from Harry Potter, and in the classical world, “Aquarium” from Saint-Säens’ Carnival of the Animals. Not only is this raised 4 in the accompaniment of the Wonder theme, but it is also the single melodic pitch that enters repeatedly. The scenes in which this theme occurs in Interstellar certainly qualify as invoking a sense of mystery. It is also worth noting that the theme’s major-mode setting is well matched with the positive outlooks of the characters in the scenes described.

Striving / In Control

Like the love/action theme, another of Interstellar’s musical themes has a dual meaning. Hear it below in one of its many forms below:

It is first heard when Cooper manages to direct the flying drone by remote, clearly demonstrating its association with the “good guys” in control. This application of the theme is also heard when Cooper is shown around the NASA base and it seems that things are under control despite the desperate situation, and the first portion of Murph’s discussion with Prof. Brand on his death-bed, as she feels confident that she will continue where his work left off.

But more often, the theme is heard in scenes where the protagonists are striving towards some immediate goal. This goal can be the understanding of a scientific concept, as when Murph is discussing possible problems of Prof. Brand’s physics equation, when Murph is striving to understand the nature of the “ghost” in her room that she says felt “like a person”, or when Cooper is trying to figure out how to communicate with Murph across the dimensions. But striving may also take a more physical form, as when Murph is trying to convince Tom to leave the farm for his own safety, when Cooper is struggling to overcome the noxious gas flooding his helmet on one of the prospective planets, when Cooper and Brand are trying to convince Mann not to open the airlock on Endurance before he has secured an airtight contact, or when Cooper and Brand are attempting to dock with the out-of-control Endurance. Despite the differences in the individual scenarios above, they all share the feeling of striving to achieve a clear and immediate goal.

Notice how the theme is structured so as to suggest a slow ascent, as though struggling to climb a musical mountain: it begins on the first note of the scale as a kind of home base, and the next note moves to the second note of the scale before it stops in its tracks. The next phrase reaches a note higher to scale degree 3 before it seems to lose confidence and fall back down to 2. The third phrase actually launches the melody up to scale degree 5, but suffers the same fate as the previous phrase as it sinks from 3 to 2 at its end. Only with the fourth phrase does the music reach up to 4 and finally 5 as a concluding summit to the theme. This sort of progressive back-and-forth between rising and falling motions is typical of themes used to depict a sense of struggle, another prominent example being the Force theme from the Star Wars saga. And like the Force theme, Interstellar’s Striving/In Control theme is in a minor key, which intensifies the sense of struggle in the theme through its veil of negativity.

Conclusion

Unlike most science-fiction films, Interstellar has at its core an emotional story of love between a father and his daughter. Appropriately, Hans Zimmer places the Murph and Cooper theme front and center in the score, and further emphasizes the relationship with another theme that can signify familial love. Of course, since the film also includes some riveting action sequences, the score does make use of an action theme, but in typical Zimmer style, this theme serves two different functions as it is also the familial love theme. Similarly, the Striving/In Control theme can signal two different but related states in the actions of the protagonists. And Zimmer also captures Interstellar’s focus on the wonder of the natural world in a separate theme. Thus, the score provides an effective glue for the film by drawing emotional links between various events, character motivations, and visual spectacles that might otherwise seem rather disconnected. In short, Zimmer’s score helps to communicate more clearly the emotional crux of the film.

Coming soon… My 2015 Oscar Prediction for Best Score.

Kudos for this excellent in depth analysis but despite being a film music journalist, composer interviewer and musician, so I know my eggs, I just cannot bring myself to purchase the CD (or CDs!) for Interstellar. I found both the film and scoring very underwhelming and certainly cannot attribute to it anything from the analysis here. It just left me stone cold. Is it just me?

Cheers, Saxplayer67. No, I don’t think it’s just you. It think there are aspects of the film that many find difficult to reconcile. What I mean is, the narrative of Interstellar is a mixture of extremes. On the one hand, it strives to be as scientifically accurate as possible yet on the other, it is at its heart a love story between a father and daughter. The fact that these objective and subjective strands are polar opposites can make the meaning of the narrative difficult to interpret, perhaps deliberately so. Are we to understand that the film actually espouses the old adage that “love conquers all”? How could we, when the only way that solution is able to be enacted is through the highly objective world of scientific knowledge? With the film’s meticulous attention to scientific detail, are we to understand that knowledge and objectivity are really the key to our future? Given that love provides the final answer to the film’s problem, it’s difficult to see it that way either. Maybe its message is that head and heart need to be balanced if we are to move forward as a species, and perhaps that there needs to be much more on the side of objectivity than there currently is. The film does, after all, make more than once reference to a public that would not understand the need for scientific endeavor at a time when the planet’s resources are quickly disappearing.

In short, I think Nolan’s films are always complex structures that require considerable thought and/or repeated viewings to digest exactly what it seems to be saying, and even then, not everyone will agree with its stance. (Mikey’s comment below is a prime example.)

in reference to the “polar opposites” you suggest of science and love in the film, and that these needs balancing somehow…I believe Interstellar meant to suggest that these are not the opposites that most describe them to be, but a universal force. You can begin to explain emotions by naming chemicals and the reasoning behind them (to produce a successful species), but I believe the film intends to express that perhaps these are not separate at all…but a natural part of the universe, all encompassing thought, emotion, time, and space in ways we cannot begin to study. and to remember that it’s not the questions we are able to ask science, it’s the questions we havnt enuf knowledge to be capable of asking. yet.

Bullshit.

I think Interstellar is the only Chris Nolan film I’ve seen… What I do feel is that the film started out wanting to be based accurate scientific knowledge and then it turns on a dime, when the previously cold fish lady crewmember starts talking about love and having faith – but not in a context of faith in God (of Whom I am a believer). Then the film goes all 2001/Black Hole/AI on us (the latter two films I love) and the science goes out the window. The ear shattering music didn’t help the film at all, it actually spoiled it for me and I bought the novelisation, to get the whole story without the noise but overall, I don’t see why this film – and director/writer/producer – is so acclaimed. I love science fiction (more so older fare) and of course music and I don’t think this production did any favours to any of it. IMO of course!

> it turns on a dime, when the previously cold fish lady crewmember starts talking about love and having faith – but not in a context of faith in God (of Whom I am a believer).

That is exactly the spot I felt the film inexplicably change as well and the reason why I thought the attempted fusion of reason and passion didn’t work all that well. I actually think the film works better as an advocate of reason over passion despite its attempt to be something of the opposite.

I think she was actually referring to Jesus, that’s what I got from her speech…she just didn’t say, the Hollywood people would have censored her anyway…God brought love to the world through Jesus, and it’s a much larger force in the universe than any scientist likes to let on…and in reference to the music, he chooses organs for almost all his expressions, I believe this is an important reference to what the movie was trying to express, we are all connected through God, across time, space, and dimension..and He built it with matter, space-time, energy building blocks, maybe someday we’ll be able to measure it, but unlikely…according to Solomon’s story, he was the most intelligent man who ever lived, but his knowledge was but a hairs breadth compared to God’s infinite knowledge

For me the purported reason/passion or objective/subjective tension is a false dichotomy. I’m passionate about reason and science, as are the film protagonists. The passion for science, the passion to save humankind and the passion between the father and daughter are all manifestations of passion. They are distinct but interrelated, with each being a means to the other.

I’ll have to think through how or whether that is well expressed musically, but the musical analysis should not be judged according to an artificial dichotomy.

I know what you mean, Murray. I was not suggesting that there is an all-or-nothing mentality to the reason vs. passion dichotomy, but only that when it came to making decisions in the film, the filmmakers seemed to be gnawing away at the idea that we should be guided more often by our emotions rather than a thought-out calculation. I think Brand’s speech about love being “something more” strongly supports this. The crew voted to go the rational route with Mann’s planet and look what happened – disaster that nearly killed everyone. Brand’s idea of following one’s heart because it intuitively feels right turned out to be a better decision in the end as the final planet seemed like “the one”.

In any case, I dislike pigeon-holing things or creating black-and-white distinctions, and in this film, there is certainly overlap between reason and passion as you point out. I would simply say that the dichotomy we’re talking about concerns not whether characters are entirely filled with one or the other, but rather which side they prefer when making decisions.

Unlike Interstellar, I think that the science fiction films that succeeded with emotion in a science fiction context were Enemy Mine, AI and Bicentennial Man. It’s a subgenre I call ‘science fiction with a heart’. This can be equally applied to the scoring of each, even though Jarre turns on a dime with the mixture of electronics and orchestra, with much dissonance and also beauty. But it works very well and is one of my fave scores (as are the other two I mention above).

I was looking for an analysis for Hedwig’s theme and stumbled upon your blog. Then, after some more browsing found this article. I want to thank you for your work, it’s great information.