English composer Gary Yershon has largely staked out his career in various realms of dramatic music, scoring mainly for theater but also for television, radio, and film. His experience in writing original music for feature films has been for the recent films of director Mike Leigh, including Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), Another Year (2010), and now Mr. Turner (2014), which marks his first Oscar nomination for Best Original Score.

Mike Leigh’s films are by no means of standard fare. His filmmaking process relies on actors’ improvisations on a basic premise and intensive, method-like acting, which involves such techniques as thorough study of characters’ psychological motivations, personal identification with their emotions, and rehearsal of hypothetical scenes for character development. Filming begins only once the content of the scenes have solidified and been polished up.

As a result, Mr. Turner, a film based on the late life of the English pre-Impressionist painter J.W.H. Turner, is remarkably lifelike, focusing on dialogue, facial expressions, and character interactions that simply ring true. With this emphasis on realistic portrayal, non-diegetic music—which is unrealistic by its nature, standing outside the world of the characters—is necessarily pushed to the sidelines both in placement and overall length at roughly thirty minutes for the whole score. Thus, while most films use non-diegetic music to accompany particularly emotional scenes, music in Mr. Turner is absent even when emotions seem to run high, as when Turner witnesses his ailing father’s death, falls in love with Mrs. Booth, or feels compassion for the struggling fellow painter Benjamin Haydon.

Instead, Yershon’s score primarily performs three other functions that non-diegetic music can have. First, it serves as connective fabric across the film’s transitions from one scene to another. Second, although it rarely offers insight into the thoughts of the characters at particular moments, it does suggest several of Turner’s traits more generally, in a way not unlike character themes in other films. And third, it loosely suggests an emotional arc that corresponds with Turner’s character. I explore each of these functions in the following film music analysis of Yershon’s score.

Transitions

Most of the non-diegetic music in Mr. Turner appears in transitions or miniature montages, when dialogue is minimal or absent and brief segments are strung together before settling into the next scene. Along with the emphasis on highly refined acting and meticulous attention to gesture and dialogue, this marginal use of music gives the film the feel of a luxuriously-produced filmed play, which speaks to Leigh’s extensive experience in theater. In Mr. Turner, the transitions usually involve relatively large shifts in time or place and so, without music, could be quite disorienting. As Claudia Gorbman remarks of the “classical Hollywood” score (ca. 1930-1950) in her book on film music, Unheard Melodies:

As an auditory continuity [music] seems to mitigate visual, spatial, or temporal discontinuity. Montage sequences—calendar pages flipping, newspaper headlines spanning a period of time, citizen Kane and his wife growing apart at the breakfast table over the years—are almost invariably accompanied by music.

Music also bridges gaps between scenes or segments; … Typically, music might begin shortly before the end of scene A and continue over into scene B.

It is unusual, however, for this transitional function to be a score’s primary usage in a film. In Mr. Turner, the transitions most often depict Turner sketching in the natural landscape, and a few are more like short montages, as when his father quickly declines in health and when Turner is seen shortly after his father’s death, fishing then walking to a brothel.

Many of the transitions in Mr. Turner are also unusual in that the music begins after the beginning of the next scene rather than before it. This reduced reliance on non-diegetic music not only gives the scenes a greater feeling of reality, but also endows them with a starkness that allows the events onscreen to speak for themselves in a powerful, and sometimes uncomfortably gritty, way. After the scene where Turner “has his way” with his housemaid, for instance, there is a sudden cut to the artist walking through the landscape. Only after a few seconds does the music enter, allowing the shock of the previous scene to be retained a moment later, enhancing its effect on the viewer.

General Characterization

Since the score is essentially relegated to the transitions, it does not function in the usual manner, in which the emotions of the characters are clarified within various scenes. Nevertheless, the score does contain three themes that suggest aspects of Turner’s personality as portrayed in the film. Here is the first theme to appear:

In the first entrance of this theme in the main title, the unaccompanied instrument—a sopranino saxophone—instantly implies an element of solitude, which corresponds with Turner’s romantic situation for much of the film. The saxophone, however, is played with a piercing tone and moves between many of its pitches with a sliding technique known as glissando, all the while winding downward in a strange, chromatic line. Not even a regular pulse is present to give the theme some grounding in a rhythmic meter. These attributes produce an odd, unappealing sound that one could easily liken to Turner’s often uninviting social manner, which frequently consists of various forms of grunts in place of a verbal response.

A second theme appears within the same main title cue, one that seems to function as an alternate or perhaps an extension of the more pervasive first theme:

This second theme is set in a regular meter, has a discernible tonal center, and is usually scored for string quartet, all of which can be heard to evoke the more dignified side of Turner that we see mainly in connection with his peers at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. At the same time, the music is mildly dissonant, suggesting that residues of Turner’s abrasive manner remain even in these more respectful settings. Take, for instance, his “improvement” of one of John Constable’s paintings by unilaterally deciding to paint a bright red buoy in the foreground of a seascape, which naturally raises Constable’s ire.

The main title contains a third theme that sounds as follows:

This theme is scored for the clarinet in the instrument’s warm, low register, or what is known as its chalumeau register. Along with its clear major-key setting, the theme suggests something of Turner’s softer, tender side that we see, for instance, in his relationship with his father and especially with Mrs. Booth. Notably, we hear the theme when William is shopping in the market for Turner, and as the widow Mrs. Booth and Turner walk happily through a meadow, arm-in-arm. Together, the three themes sounded in the main title cue help to establish some of the contradictions of Turner’s character, which figure prominently in the film.

Turner’s Emotional Arc

Late in Mr. Turner, a handful of scenes state a fourth theme that, together with the first three described above, traces the general emotional arc of Turner’s character.

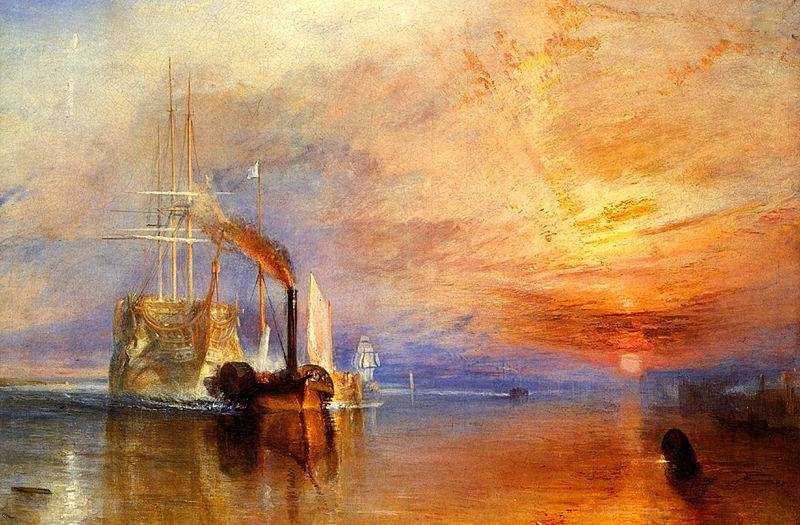

We first hear this new theme as Turner has himself tied to a ship’s mast in order to witness a sea storm first hand. It also appears when Turner and a few friends row along the Thames, viewing the “Fighting Temeraire,” an old military ship that became the subject of one of Turner’s most famous paintings (seen below).

The theme then returns when the view of a landscape with a passing train that is emitting steam inspires a new painting from Turner. It occurs one last time as we see the artist sitting on a pier, sketching the seaside.

The above scenes not only depict Turner observing the objects of his fascination, but also in happier times, as he is in a relationship with Mrs. Booth and has taken to spending more time with her. As a result, we see a side of Turner that was not apparent before—a nurturing, loving side that further adds to the apparent contradictions of the character. (His attitude towards his ex-mistress and two daughters, for instance, is one of complete apathy.)

Up until the entrance of this fourth theme, the music has been dominated by the three Turner themes discussed above, most of which express either negative traits or his more business-like side. In focusing instead on his more positive aspects, the fourth theme corresponds to the shift we witness in Turner to a more contented state of mind. The theme suggests these positive aspects in several ways, perhaps most obviously in its clear projection of a tonal center. The melody begins on the note A and descends through E to the A an octave lower. Together, these notes A-E-A strongly establish A as a center. It is also in a slower tempo than the other themes and employs tones in various instruments throughout the score (here, a soprano and sopranino saxophone) that are mellower than the high, piercing saxophone of the first theme. These qualities all endow the theme with a more placid atmosphere that corresponds with Turner’s more positive attitude in the latter part of the film. Although there remains some dissonance in the theme’s harmony, it is a very mild dissonance that is subsumed within a more stable and pleasant environment, as though suggesting that Turner’s more abrasive side has been tamed by his romance with Mrs. Booth.

Conclusion

Unlike traditional film scores, Gary Yershon’s Mr. Turner functions mainly at the film’s peripheries in transitions and montages. Yet it still manages to capture general aspects of both Turner’s character and his emotional trajectory through the film. All of these functions reflect the fact that the film is less a biopic on J.W.H. Turner as it is a character study of him done in a very realistic way. As such, non-diegetic music has a small part to play, expressing broad aspects of the character and his progression only “from a distance”, and allowing the naturalistic scenes to speak largely for themselves.

Coming soon… Interstellar.

Interesting once again! Looking forward to the final one 🙂

-Paul