Saving Mr. Banks earned veteran Hollywood composer Thomas Newman his 12th Oscar nomination and the 2nd in consecutive years following last year’s nomination for his score to Skyfall. Being a film about the making of Disney’s 1964 film Mary Poppins, one might expect the non-diegetic score of Saving Mr. Banks (that is, the music that the film’s characters do not hear) to draw on the latter’s classic songs such as “Chim Chim Cher-ee”, “A Spoonful of Sugar”, and “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious”. But the film’s score is instead planted firmly in Newman’s own style, which avoids the danger of the songs becoming parodies of themselves and allows the film to tell its story with a musically fresh palette.

Regarding style, Newman’s music is often dubbed as minimalist since the repetition of short segments of music (ostinato) plays such an integral role. But the “Newman sound” also incorporates unusual combinations of instruments (especially involving percussion and/or plucked string sounds), a high proportion of sampled sounds, and syncopated rhythms that betray a rock and pop influence. Thus, the style of Newman’s music is probably better described as “eclectic minimalism”, his score to Saving Mr. Banks being no exception.

The film tells the tale of the innumerable objections raised by the author of the Mary Poppins books, Pamela L. Travers (Emma Thompson), in having the Disney Studios bring her story to the big screen. As the film unfolds, we learn through a series of flashbacks that the deep meaning of the books for Pam lies in their intimate connection with her childhood and love for her father, Travers Goff. Pam’s attachment to the books, however, nearly paralyzes the filmmaking process, a conflict that is played out mainly in her relationship with Walt Disney himself (Tom Hanks). It is therefore no surprise that the three most prominent themes in the film’s score revolve around these two characters.

In the following film music analysis, I provide a detailed look at these three themes and discuss their use in the film. With the exception of the Disney’s theme, Newman’s themes tend not to represent characters or things in the manner of a leitmotif, but are more diffuse, each one expressing a consistent feeling that applies to each scene somewhat differently.

Pam’s Lighthearted Theme

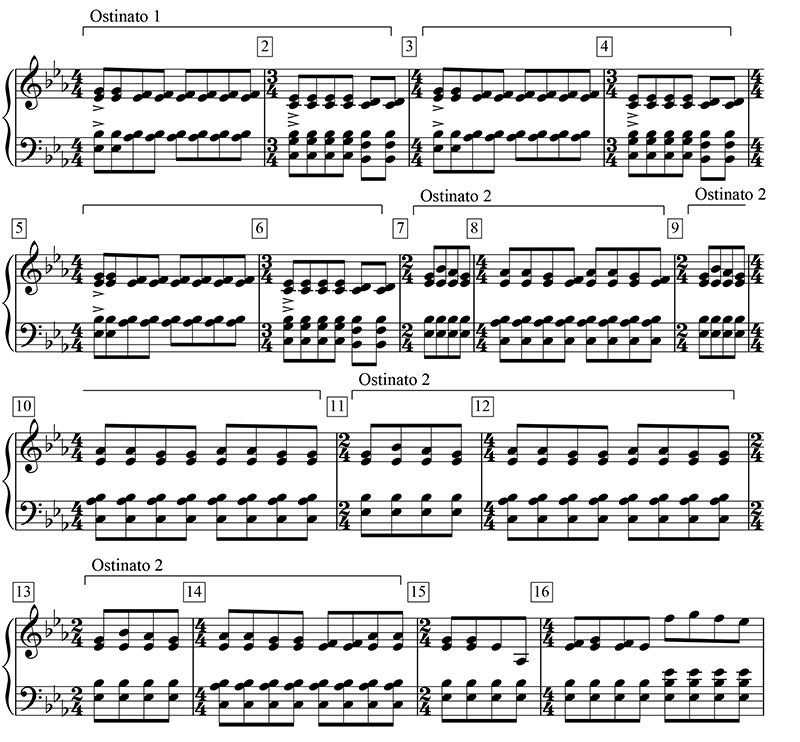

This theme is first played during Pam’s first flashback, which shows her father jokingly asking her where his daughter (Pam) has gone. The scene demonstrates the close relationship between the two and is essentially one of Pam’s happy memories. Newman mirrors these attributes in his music for the scene, given below.

Most obvious in the theme is its bustling, energetic quality, signalled by the continuous stream of bopping eighth notes and its peppy irregular meter. But notice that the theme is composed of Newman’s favoured technique of ostinato (two separate but related ostinatos are shown here), and that in the inner voices there is a near constant use of the notes Eb and Bb, the two tonal “pillars” of the theme’s E-flat scale, being the tonic and dominant notes, respectively. Combined with the sunny major-key setting and the jaunty, mild dissonances of the pop-style chords, the overall effect is one of an energetic playfulness that aptly characterizes the scene.

The theme, however, is also heard in two other scenes. In one of these, Pam is picked up by the chauffeur Ralph, who drives Pam around during her American visit. Pam is unhappy with everything Ralph says to her and the music obviously suggests that we see the humorous side of all this. In the other scene, Pam is seen typing away at another Mary Poppins book after finally signing on to the rights of the film. Here, the music suggests the cheerfulness and rejuvenation Pam feels in having the weight of the film lifted from her shoulders by resolving her disputes with Walt Disney, an interpretation that Newman’s theme makes crystal clear. Given the theme’s usage in the above scenes, I refer to it as Pam’s Lighthearted Theme.

Pam’s Tender Theme

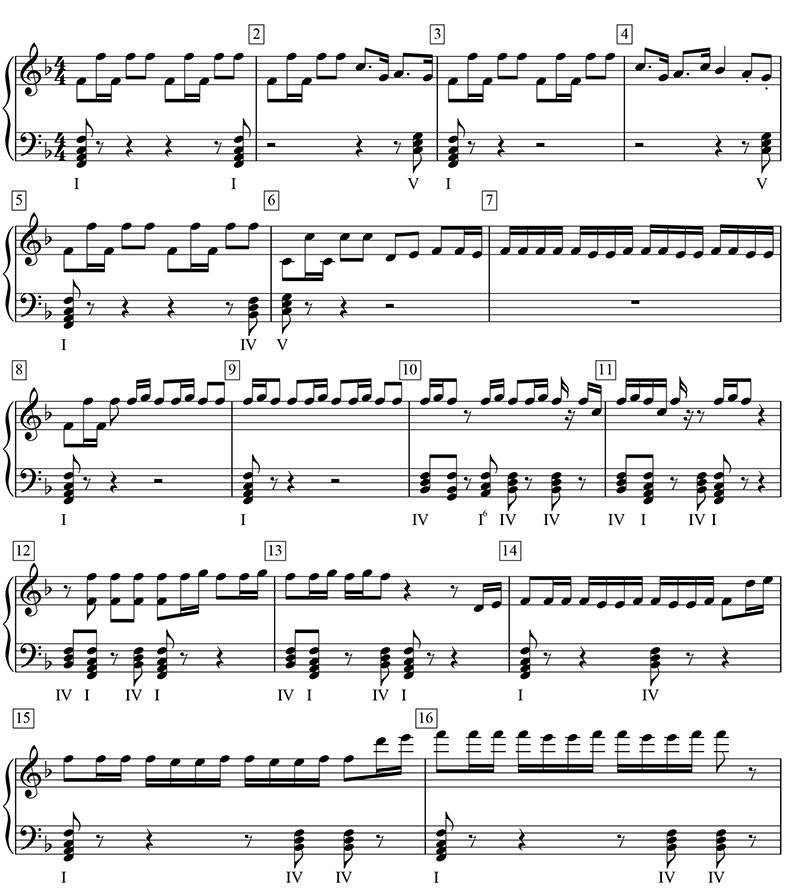

We first hear this theme in another flashback, this time of Travers telling Pam that their horse is actually an uncle who was turned into the animal because a witch hated the sound of his laugh. The music Newman writes for the scene is as follows:

As the film proceeds, we begin to understand that moments such as this were formative for Pam since her bonding with Travers through stories of fantasy had an enormous influence on her creation of the Mary Poppins books. Hence, Newman infuses the theme with warmth through its moderate tempo, lyrical melody, and lush accompaniment. But the harmony plays an important role here as well, as the first sixteen bars are composed of only two chords: I and IV, or the tonic and subdominant. Chord progressions that move between I and IV tend to have a very relaxed sound and can even take on a spiritual tone, especially when placed in a warm setting as here. (Indeed, when a IV-I progression ends a piece, it is often colloquially referred to as a “church cadence” or “amen cadence” since they are often set to the word “amen” at the conclusion of a hymn.) These musical features help to emphasize the strongly emotional quality of Pam’s relationship with her father, and hence I call this Pam’s Tender Theme.

This theme returns at three other key places in the film. First, after the young Pam witnesses Travers nearly get fired from his position at the bank for drinking on the job, Travers impresses on Pam the importance of holding on to ideas of fantasy in order to cope with the difficulties of reality. We hear it again when Ralph tells Pam about the difficulties his disabled daughter faces on a daily basis. And it is heard one last time when young Pam sees her father just after he has died. In all three cases, the theme is rescored largely for the piano, lending the scenes a more intimate and poignant quality.

Disney’s Theme

The introduction of the character of Walt Disney in Saving Mr. Banks is accompanied by the following music:

Certainly, this is authoritative music, befitting of the head of a major company. But this is no ceremonial march. Instead, it is buttressed with orchestral blasts (seen in the left hand), many of which are syncopated rather than occurring on-beat, and its string ostinato (seen in the right hand of the first bar) has an energy that goes beyond a march-like accompaniment. Finally, it uses nothing but the simple chords of I, IV, and V. All of these features are suggestive of the Copland-esque sound of Americana that made its way into film with the famous American western films The Big Country (1958) and The Magnificent Seven (1960). Listen, for example, to the openings of each below.

The Big Country (listen up to 0:37):

The Magnificent Seven (listen up to 0:28):

While nothing in either clip is directly quoted in Disney’s Theme, the same Americana flavour is unmistakable in the latter through its syncopated accompaniment chords, driving ostinato, and simple harmonies. Thus, the suggestion of Disney’s Theme is not of just any corporate boss, but a specifically American one.

Disney’s Theme is heard at one other point in the film: when Pam reluctantly arrives at Disneyland for a visit to the park with Walt himself, all in an attempt to prevent Pam from keeping the rights to the Mary Poppins story and further obstructing the film. The presence of the Disney Theme at this point is thus hardly inappropriate, as Walt is once again making a splashy entrance, this time at the gate of his own park. But the music also implies the extravagance and bustling nature of the amusement park as a whole.

Conclusion

As we have seen, Newman’s treatment of the first two themes above is broader than the traditional leitmotif in that his themes are not simply a signal of a particular character or object, but rather of an emotional expression that applies to a particular character in various situations. And even his theme for Walt Disney is itself widened to include the grandeur of the Disneyland park, thus again moving beyond a simple theme-to-character relationship. This more diffuse approach to theme composition fits the film quite well as the very small number of themes allows for a high degree of continuity in a film that relies heavily on a disjointed narrative through several flashbacks. In addition, Newman’s score for Saving Mr. Banks draws largely on the composer’s own personal style rather than on the classic songs from Mary Poppins. In this way, the contrast between the cheerful fantasy world of the Mary Poppins story and the “real” world of Pamela Travers with her more serious story that wavers between tragedy and comedy is brought poignantly to the fore.

Coming soon… Alexandre Desplat’s Philomena.