Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (or in the U.S., Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone) was the first in the series of seven fantasy novels that chronicle the adventures and coming of age of J. K. Rowling’s famed boy wizard, Harry Potter. Released in 1997, the novel ignited the imaginations of countless fans and the seven novels together have sold over 450 million copies to date, making Harry Potter the best-selling book series in history.

The Harry Potter films have continued the success of the franchise, collectively earning over $7.7 billion at the box office. John Williams scored three films in the series starting with the first, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s (or Sorcerer’s) Stone. Of the several themes Williams composed for the film, the most prominent is “Hedwig’s Theme”. Although this theme may originally have been intended only for Harry’s pet snowy owl named Hedwig, its pervasiveness throughout the film captures much of the general air of mystery and wonder that a child like Harry would feel in becoming part of a world filled with wizards, witches, and magic.

The concert version of Hedwig’s Theme actually incorporates two themes: Hedwig’s Theme and the Flying Theme (or “Nimbus 2000”, the name of Harry’s broomstick). Hedwig’s Theme breaks down into two closely related sections I simply call A and B. In this audio clip, A is heard from the start, B begins at 0:17, A appears again at 0:45, B at 1:01, and A once more at 1:18:

Below is my film music analysis in which I take a look at some of the musical techniques Williams uses to convey the feeling of magic and mystery associated with the world of Harry Potter.

The A Section

Orchestration

Probably the most distinctive feature of the first A section is its orchestration. It opens with a solo that combines synthesized and real sounds of the celeste, a keyboard instrument whose keys strike metal bars that sound like small bells. Because the celeste is not exactly an everyday instrument, it has something of an ethereal sound, all the more so in Hedwig’s Theme since the sound is electronically manipulated and therefore literally unreal. But at the same time, the celeste is associated with the imaginative world of children primarily through the “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” from Tchaikovsky’s ballet, The Nutcracker, whose fanciful creatures are presented through a young girl’s dream.

Harmony

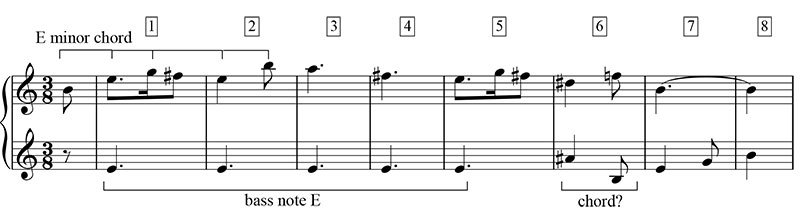

Harmonically, Hedwig’s Theme is essentially in the key of E minor, but the chord progressions are anything but typical for a minor key. As shown in the example below, the first two bars of the theme outline the E minor chord, and the bass extends the E into bar 5, all of which clearly establishes the key. But in bar 6, we get a very strange chord:

Taken together, the notes of bar 6 are B-D#-F-A#, which is similar to E minor’s dominant seventh chord, B-D#-F#-A. Had Williams given us the actual dominant seventh, the music would have been within the realm of the ordinary. But by substituting F# with F, and A with A#, he instead creates a chord that cannot be fully explained, much like the workings of a wizard’s magic.

As shown in the example below, bars 9 and 10 of the theme return to the original E minor chord along with the same opening melody. But in bars 11-12, the music suddenly heads in a new direction, sounding out three more minor chords that bear no relation to one another. The resulting sound isn’t just unusual. Since the progression is inexplicable, it creates an aura of wonder as well, a perfect musical accompaniment for a world of magic and mystery. Indeed, Williams even writes “Mysterioso” at the start of the score.

Williams has used a series of minor chords before to accompany similarly mysterious circumstances: the opening scene of E.T., when the aliens are collecting samples of the Earth’s plant life and we are unsure at this point whether or not these aliens are friendly, and in Raiders of the Lost Ark as the theme for the Ark itself, whose divine source of power is shrouded in mystery. Hear these two passages below (from the start of each clip).

From 0:30 in this clip:

From the start of this clip:

In Hedwig’s Theme, after the string of minor chords, Williams ends the section with two chords (see above musical example). Most themes or sections of themes usually close with two cadence chords: dominant and tonic, in that order. In Hedwig’s Theme, we do end on the tonic (in the last bar above) but the chord preceding it is not the dominant, it is the dominant of the dominant, which leads us to expect the dominant chord next. Instead, Williams heads straight into the tonic. This ousting of the usual dominant chord shifts the sound of the cadence out of the ordinary world and moves it into the realm of the strange and ethereal.

Melody

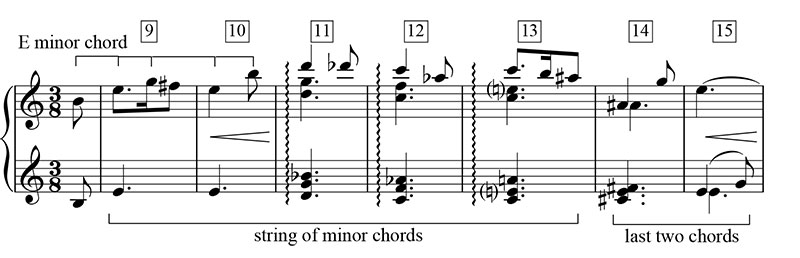

Below is the melody for the entire A section of Hedwig’s Theme, which itself divides into two phrases.

While the first five bars are entirely in the key of E minor, the sixth bar introduces a note foreign to it— F natural, which is the lowered form of scale degree 2. As we saw, this note is part of the strange dominant-like harmony of the bar, but at the same time it also creates odd-sounding intervals in the melody. With the previous D# the F takes the minor third we would have had and “squashes” it into a diminished third, and with the following B it “squashes” a perfect fifth into a diminished fifth (or tritone). These same intervals are also heard at the end of the A section in bars 13-15, now with an extra intervening note:

Both of the A section’s phrases therefore end with these strange intervals, which helps impart an air of mystery to the theme.

Another note foreign to E minor that Williams introduces is A#, the raised fourth scale degree (#4), which first appears in the melody in bar 13. Notice that this note comes a half step (or semitone) down from the preceding B, which is scale degree 5. This kind of semitone motion from 5 to #4 in a minor key is another musical feature that has associations with mystery. Saint-Saëns’ famous piece, “Aquarium” from Carnival of the Animals, is a prime example. The melody’s swaying back and forth from 5 to #4 in minor certainly creates a strange and mysterious aura (from the start of this clip):

And even in film, in the well known theme for “Harmonica” from Once Upon a Time in the West, motions from 5 to #4 and back to 5 in a minor key create an appropriate sense of eerie mystery for a character about which the audience and other characters in the film know so little about (hear from the start of this clip):

I would also point out that the melody of the A section uses all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, and so in an abstract way could indicate that wizards and witches can inhabit both the non-magical world of muggles (or non-magical folk, as represented by a “normal” E minor scale) and the supernatural world of magic (as represented by all the other notes outside the E minor scale).

Rhythm and Meter

Many of Williams’ themes for blockbuster action films are marches, which are always set in a two- or four-beat meter. Hedwig’s Theme is different, however, because it is set in a three-beat meter, which creates an entirely different feel. In the moderate waltz-like tempo of the theme, the three-beat meter evokes a feeling of elegance and grace that befits a wizard’s ability to get out of many jams quickly and easily with, for instance, the simple casting of a spell. But at the same time, this triple time creates a lightness and buoyancy in the music, a floating quality that captures the feeling of taking to the air, as wizards so often do.

The B Section

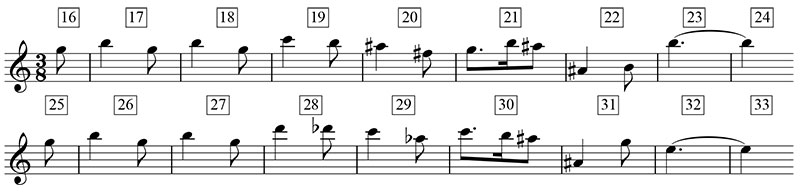

The B section of Hedwig’s Theme shares many of the musical features of the A section: it is exactly the same 16-bar length, it retains the same orchestration in the celeste, and it closes with virtually the same 6-bar passage. Here is the entire B section:

But there are some significant changes in the B section as well. For example, the harmonies at the start of bars 20 and 22 are from a family of chords known as “augmented sixths”, which tend to have an unearthly sound when paired with a sustained tonic note (pedal point) in the bass, as here. Again, Saint-Saëns’ “Aquarium” is another well known example of this.

The melody of the B section differs from that of the A section in that it does not sound the tonic of E minor until the very last note, instead hovering mainly around its dominant note. Since the dominant is the fifth note of the scale, it is, in a sense, “high up” from the “ground” tonic note with which the theme began. Williams’ avoidance of the tonic therefore gives the theme a feeling of being suspended in the air like a wizard on his broomstick.

Repetitions of Hedwig’s Theme

Both the A and B sections are repeated, then the A is stated one last time before the piece moves into the “Nimbus 2000” theme. With the first repetition of A, Williams adds a prominent figure of rapid scales in the strings, harp, and celeste that paints a more vivid musical picture of the sorts of aerobatics that wizards, witches, and their owls engage in. The last repetition of the A section continues this rushing figure in the strings but now sounds the melody more powerfully in the French horns. In the Harry Potter films, this strong scoring of the melody in the horns is appropriately associated with views of the Hogwarts School, which is housed in an impressive and imposing castle.

Conclusion

Hedwig’s Theme is one of the more flexible themes in Williams’ oeuvre as it does not represent a single specific character or thing the way, say, the Imperial March represents Darth Vader and the Empire. Instead, Hedwig’s Theme seems to represent the world of wizards and magic more generally. But even so, because the theme is usually heard in the films when Harry is the focus of attention, it may well be thought of as mainly representing the magical world as seen through Harry’s eyes. This would explain the childlike sense of wonder heard in the ethereal sounds of the celeste, as well as the features that suggest strangeness, mystery, and the magic of flight. Thus, as we have seen throughout this series of posts, Williams creates his effect by aligning many different aspects of the music towards a common expressive goal.

Hi, Mark. I’m a very enthusiastic on film scores and found your blog reading the Brazilian “Revista Cultura” magazine. Scores are not the most popular kind of music in anywhere, you know, but I love it and texts so great as yours are difficult to find. Congratulations for your work!

Felipe Essy

Thanks, Felipe. You’re right it is hard to find analytical work on this music. I’m doing what I can to try and change that. 🙂 BTW, a more extended analysis of Williams’ Superman March is now posted here – it draws on the points I gave in the Brazilian article but takes them further. Cheers.

I agree! Thanks for the insightful analysis.

Hi Mark! I believe that “Hedwige Theme” is plagiarism. Please listen to Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns “Animal Carnival” part of the “Aquarium”. May be will analyze these two works on the subject of plagiarism?

Hi Mark,

Great analysis. Did you notice that the A and B melodies have 1 note in each which shifted in the repeat? Just when I thought I nailed the melody in my head, when after listening to it again I heard the off-notes in the second version!

I wonder why he did that.

Thanks, KL. I had noticed the note in the A section that was changed (a D# becomes D natural), but I had not noticed the note in the B section, where a B is subtly chnaged to C. So thank you! As to the reason, I don’t know for sure, but Williams is a master of variation technique. But usually this variation occurs within the confines of a rather short 8-bar theme, like the A or B sections of Hedwig’s Theme, which are great examples. But when Williams restates the whole 8 bars of a theme, he usually keeps the notes the same, so this is unusual that way. Even so, I would attribute it to his tendency to vary his ideas.

Yeah, the B section’s second version (C instead of B) is really hard to nail down when singing it out, cos it’s just so unnatural!(not that unnatural is bad…) Thanks for letting me feel good about myself for having spotted it, hah… 😉

Lol, KL. No problem. It’s good to have others’ ears and eyes spot new things!

Hey Mark,

I loved reading this. I am excited to go through all these posts and read them. (:

Stefan

Thanks, Stefan! Williams is one of my all-time favourites.

Hi Mark,

I just found this analysis and commentary. Great stuff! Thanks for this.

Have you noticed that Hedwig’s theme was altered starting with the fourth film? (John Williams scored the first three films, but not the later ones.)

From the fourth film on, the F natural in the sixth measure was changed to an F-sharp, which spoils the melody for me.

Hi Em. Thanks for the kind words. You’re right that the theme is changed in the fourth film and has the normal scale-degree 2 rather than the flat version Williams wrote. And I agree this is not nearly as good as the original.

After listening to it, I notice that there are a couple of other small note changes. The fifth note of the theme is now the raised 4th of the scale rather than the normal version, which adds a bit of that mystery I talk about in the post with the sharp-4 degree.

Also, what was Ab in the original theme now becomes the equivalent of A-natural, again rendering it the normal note found in the scale, so a bit less strange and mysterious. But that’s because of the harmony Patrick Doyle is using – the new note now fits with the new chord, so it makes sense that way.

Finally, the third last note in the original is A#, an appropriately quirky note that again suggests mystery (raised 4 of the scale). But in Doyle’s version, it’s changed to a more normal scale-degree 5 (a semitone up). And again, this is motivated by the harmony, the new note being part of the new chord.

So in a sense, it seems that Doyle is thinking more harmonically when arranging the theme whereas Williams was thinking more melodically and thwarting our expectations for “normal” notes of the scale at points where they would seem inevitable.

Hi Mark,

I was trying to analyse this theme by myself. Then ı wondered if anyone else did this kind of thing and here we go!

I am happy to read such a good analysis.

Burak

Thanks, Burak!

Hey, I just wanted to thank you for all the great analysis of these works. As many others said, its hard to find such texts on the internet. Thanks a lot! Greetings from Argentina

Thanks, Lucas! I do what I can to contribute to the growing literature on film music.

Hi!

There is no G# in the A section. Only 11 notes of the chromatic scale are used by Williams.

Anyway, well done!

Hi Marlon! But there is a G#, it’s just written as Ab in my example (bar 12 in my second example) because it’s part of an F minor chord. So all the notes of the chromatic scale are present in the theme.

Argh, sorry my fault! It was to early. 🙂

Searched for a G# the whole time and havn’t found the Ab.

Of course you are right! Thank you.

If there is a way to contact you for a few questions, let me know.

astaraeel@icloud.com

Where can i find the notes to Hedwig’s theme

Many of Williams concert versions of his scores are available in the Signature Series offered by Hal Leonard. Hedwig’s Theme is among these.

Hi!

It will be nice you add the name of chords under the note. English is not my nativ language and in this way it will be easier for me to put the chord on the right place.

Hi Aurelia. Give me a day or two and I’ll see what I can do…

Thank you for your excellent commentary. I appreciate the clearly-set examples, also. I look forward to reading the rest of your analyses. mb

I find the opening of the melody strongly reminds me of another piece, but can’t put my finger on what that is. Any ideas?

Your analysis was fascinating, thank you.

The tune doesn’t ring any bells with other pieces for me. Do you know if you’re thinking of a classical piece or something else?

Svan Lake?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1QhNz117CQ

Safe to say it was an inspiration at least.

?

The theme sound to me an awful lot like Burial of Kije from Sergei Prokofiev’s “Lieutenant Kije.”

Pingback: John Williams & The Philosopher’s Prisoner of Secrets – Peter's Site!

what is the scale of the notes in HEDWIGS theme

Interesting that AMC is playing secret of the blue moon this evening and the end song during the credits is the harry potter theme…although the former film was released in 1933…love to see your analysis and then it begs the question is John Williams just rehashing the precursor and took it to the bank? Methinks so. Curiouser and curiouser…

Hi BJ,

Glad you enjoyed the analysis. You mean Secret of the Blue Room. That end credits piece is the big theme from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Personally, I have a hard time hearing Williams’ Harry Potter theme is a rehash of Swan Lake. To me they sound entirely different and I wouldn’t say they are in any way connected. For an excellent demythification of criticisms of Williams’ film music, particularly with regard to what others hear as plagiarism, see chapter 8 of Emilio Audissino’s John Williams’s Film Music, a great read all the way through as well.

But I do think it’s interesting that the Tchaikovsky is appropriated for the Secret of the Blue Room. As you point out, the film is from 1933, which was just a few years after the introduction of sound film, or the “talkie”. In the years leading up to the talkie, music for movies was often played from anthologies full of cues composed for various emotions and images. What’s interesting is that the demand became so high for anthology music from a publisher named Belwin that, as one composer employed for the company colourfully wrote, ““in desperation [Belwin] turned to crime. We began to dismember the great masters. We began to murder ruthlessly the works of Beethoven, Mozart, Grieg, J.S. Bach, Verdi, Bizet, Tschaikovsky and Wagner — everything that wasn’t protected from our pilfering by copyright.”

So the Tchaikovsky in Blue Room is likely a kind of sustaining of an earlier standard at a time when that standard was in flux and over the next few years to turn confidently towards the original score.

Hi Mark,

I’ve just found this site after reading about John William’s inspirations for his music. Yesterday I went to an organ recital where Viernes Symphony no 4 was one of the highlights. Although the mood and tempo were very different, there was something in the intervals of the notes on the recurring theme which reminded me of Hedwig’s Theme. I was curious enough to see if anyone else had thought the same.