The main title music to the Star Wars films is probably the most recognizable cue in film music history. Ever since its 1977 debut in Episode IV: A New Hope, it has remained enduringly popular among filmgoers of all ages and no doubt played a substantial role in catapulting sales of the film’s soundtrack to over four million copies after its initial release.

The main title music to the Star Wars films is probably the most recognizable cue in film music history. Ever since its 1977 debut in Episode IV: A New Hope, it has remained enduringly popular among filmgoers of all ages and no doubt played a substantial role in catapulting sales of the film’s soundtrack to over four million copies after its initial release.

With its opening orchestral blast, John Williams’ famous cue tells us that we are in for is a tale that is larger than life, something extraordinary, something from the realm of myths. The cue, which functions both as main title music and as a theme for Luke Skywalker, retains this mythic feel throughout its entirety and yet is surprisingly diverse in its musical material. It begins with an introductory fanfare of fast and overlapping lines, then moves into a “big” tune that is slower-paced and more majestic, then sounds a gentler melody for a middle section before returning to the big tune. Yet somehow it all hangs together incredibly well, drawing us through from start to finish in an engaging and remarkably cohesive way. So besides the superficial consistencies in its loud brassy scoring, major key, and largely consonant chords, how is it that such different sections can sound so unified and keep up the mythic feel of the music? Some answers are suggested by the cue’s melody, harmony, and rhythm, as shown in my film music analysis below.

Melody

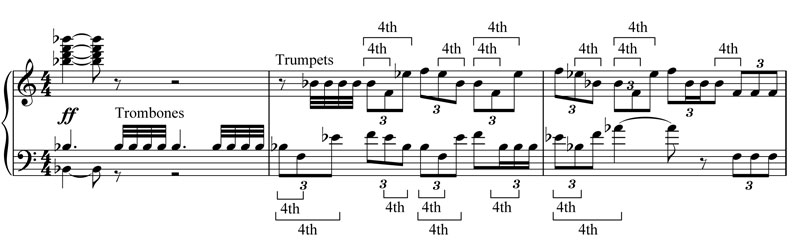

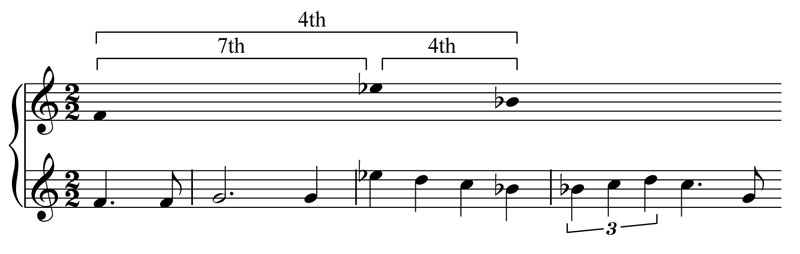

Naturally, the overlapping fanfare at the start of the cue builds up our the excitement before the big tune comes in, but more than that, it provides much of the material for the music to come. In terms of musical intervals, there is a predominance of fourths in its melody:

Especially when used in the brass, fourths tend to suggest strength and heroism. So a liberal use of them here already lets us know that this mythic tale involves some kind of hero. But a closer look reveals that the fanfare combines two fourths (and a resulting seventh) into a three-note motive that is repeated several times:

Especially when used in the brass, fourths tend to suggest strength and heroism. So a liberal use of them here already lets us know that this mythic tale involves some kind of hero. But a closer look reveals that the fanfare combines two fourths (and a resulting seventh) into a three-note motive that is repeated several times:

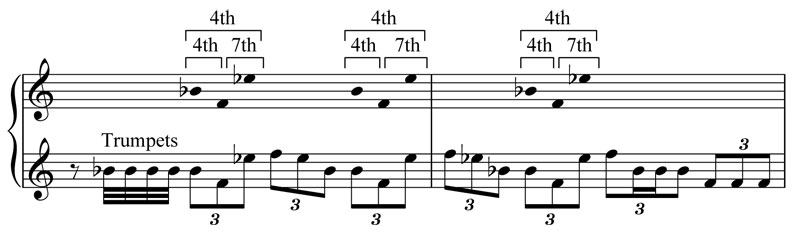

This motive then becomes a part of the big tune:

This motive then becomes a part of the big tune:

Of course the tune’s opening leap of a fifth in the trumpets is itself a marker of heroism, but notice that the tune also makes the leap of a seventh that we saw in the fanfare. In these slower note values, this larger leap has a deeper impact on us, especially being at the top of the trumpet’s range on a climactic Bb. If the opening fifth signals a hero, this second larger leap signals a superhero.

Of course the tune’s opening leap of a fifth in the trumpets is itself a marker of heroism, but notice that the tune also makes the leap of a seventh that we saw in the fanfare. In these slower note values, this larger leap has a deeper impact on us, especially being at the top of the trumpet’s range on a climactic Bb. If the opening fifth signals a hero, this second larger leap signals a superhero.

The middle section of the main title begins with a melody that may seem quite different from all that has come before. But even here, we are treated to a reordering of the three-note motive:

This time, however, the heavy brass instruments are absent and the melody is made more lyrical by being scored for strings and continuing mainly in stepwise motion. And yet, the three-note motive underpins all of this, suggesting that what we are hearing is the gentler, more compassionate side of our superhero.

This time, however, the heavy brass instruments are absent and the melody is made more lyrical by being scored for strings and continuing mainly in stepwise motion. And yet, the three-note motive underpins all of this, suggesting that what we are hearing is the gentler, more compassionate side of our superhero.

This more compassionate setting carries over into the return of the heroic big tune, which is now likewise scored for strings but also combined with French horns, a softer version of the more aggressive trumpets we heard before. It would seem that even during his most heroic exploits, our superhero manages to have a heart.

Harmony

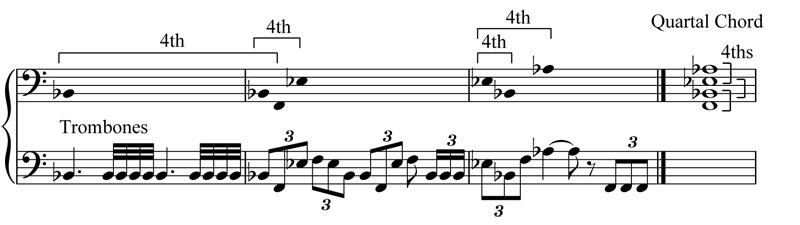

The fanfare of the main title begins with the mythic orchestral blast on the tonic chord of the cue’s key, B-flat major. The harmony of the rapid brass lines that follow is not sounded as a block chord but rather by sounding the notes of a chord one at a time. Grouping all the notes of these lines together, what results is a chord built in fourths, or what is known as a “quartal” chord (in the diagram below, I shift the trombones’ line down an octave to make it more readable):

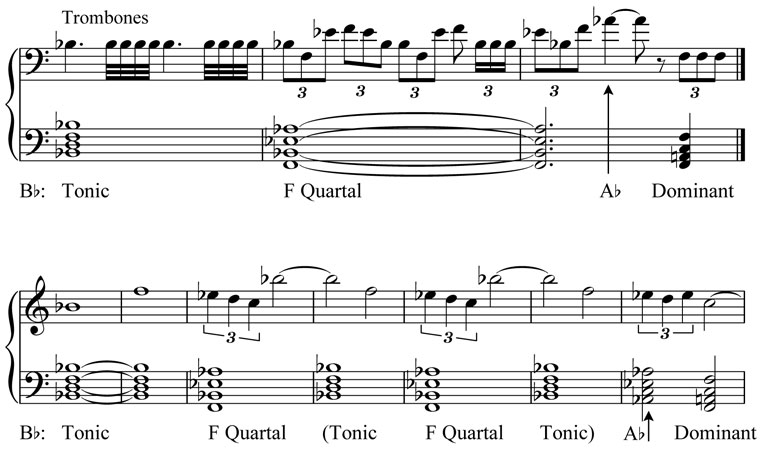

The fanfare then sounds its last three notes on the chord of the dominant (fifth note of the scale) in B-flat major. Remarkably, the big tune that follows has this very same harmonic outline (as does the tune’s return after the middle section). It begins with a blast of B-flat tonic harmony, which then alternates with the same quartal chord on F before coming to a close on the dominant chord. This dominant chord gives the music a sense of forward drive since what we really want to hear after it is a tonic to close out the phrase. When a phrase is deprived of this tonic closure, we feel that the music must press on in order to attain it. And in fact every phrase in this main title ends on a dominant—we never get to a tonic conclusion. In mythic terms, this could be viewed as a fitting musical reflection of the superhero whose job is never entirely finished.

The fanfare then sounds its last three notes on the chord of the dominant (fifth note of the scale) in B-flat major. Remarkably, the big tune that follows has this very same harmonic outline (as does the tune’s return after the middle section). It begins with a blast of B-flat tonic harmony, which then alternates with the same quartal chord on F before coming to a close on the dominant chord. This dominant chord gives the music a sense of forward drive since what we really want to hear after it is a tonic to close out the phrase. When a phrase is deprived of this tonic closure, we feel that the music must press on in order to attain it. And in fact every phrase in this main title ends on a dominant—we never get to a tonic conclusion. In mythic terms, this could be viewed as a fitting musical reflection of the superhero whose job is never entirely finished.

In addition to the blasting tonic chord, the quartal chord, and the final dominant chord, both sections also have a prominent A-flat just before the dominant, further strengthening the similarity. Compare the harmonic outline of the two below:

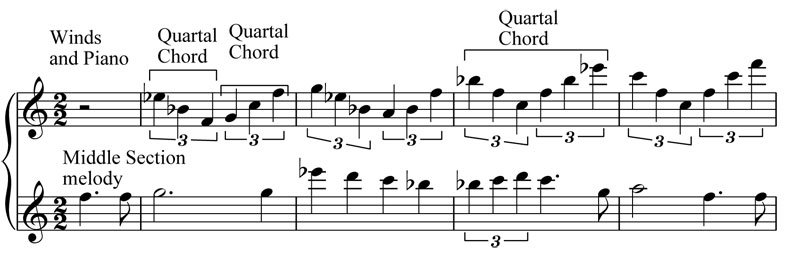

Even the middle section, which follows a different outline, contains broken quartal chords in a line given to the winds and piano:

Even the middle section, which follows a different outline, contains broken quartal chords in a line given to the winds and piano:

This harmonic connection is another way that we can hear this lyrical section as the softer side of our mythic superhero’s character.

Rhythm

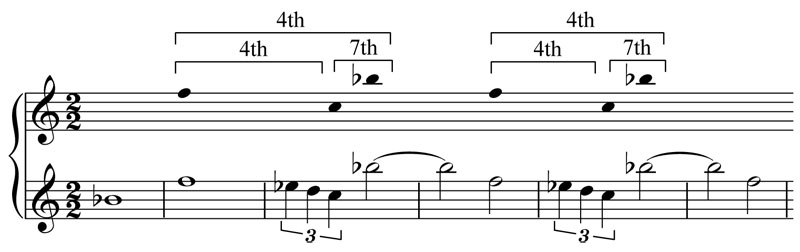

The main title’s opening fanfare sets out the rhythmic basis of the rest of the cue. It consists almost entirely of moderately fast triplets. Although the subsequent big tune slows the rhythm down with longer notes at its opening, the triplets do not disappear. Instead, they are incorporated into the tune, and although Williams writes them in longer note values than in the fanfare, they are actually played at the same speed as the fanfare’s triplets because of a change in the notation. So what we hear turns out to be the same rhythm as in the fanfare. Even the lyrical middle section retains the triplets in the wind and piano accompaniment I mentioned above. Compare all these below (triplet eighth notes in the fanfare are equal in speed to triplet quarter notes in the big tune and middle section):

In the context of a four- or two-beat time like these, triplet rhythms give the music a march-like character. In fact, these triplets are so pervasive that the entire cue might aptly be called the “Star Wars March” since it is essentially a march in all but name. In any case, the implication is of a powerful military aspect to our mythic superhero.

In the context of a four- or two-beat time like these, triplet rhythms give the music a march-like character. In fact, these triplets are so pervasive that the entire cue might aptly be called the “Star Wars March” since it is essentially a march in all but name. In any case, the implication is of a powerful military aspect to our mythic superhero.

Conclusion

The main title music of the Star Wars films has had a lasting impression on audiences ever since it burst onto the silver screen in 1977. It is perhaps the perfect sonic introduction to the mythical world we are transported to from “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away”. Certainly part of its overwhelming success has been due to its larger-than-life quality through its heavy brass scoring and its memorable, soaring tune. But more than that, the music just seems to “work” incredibly well, firmly holding our attention from start to finish. As I have argued, one reason we feel so glued to this music in the film is that the entire cue is highly unified in both its musical structure and its expressive qualities. In other words, we hear the same melodic motives, the same harmonies, and the same rhythms played again and again but in slightly different guises. But at the same time, these musical aspects are such strong indicators of the mythic superhero that a consistent emotional quality is in fact built into the musical structure. (The cue is given below in case you’d like to hear the cue with fresh ears, so to speak.) Given this powerful connection between the music’s structure and the film’s myth-based world, it would be difficult to imagine any other music working quite as well as this.

Thanks so much for this extraordinary series of analysis and labor of love. Work like yours makes the world a better place to live in.

Working on score study of Superman March and stumbled, happily, into your site, and your entertaining analysis of Mr. Williams composition. I found the replies interesting also. Thanks so much for your insight of this piece, and for helping to explain why still to this day , I get chills when l hear the first transition with those beautiful chords. As you said, it’s a feeling of anticipation. Well done.

Thanks, Melvyn. And I can’t wait to hear the piece again in Episode VII!

I LOVE your analyses on the Superman score!! Was humming the tune while reading. Your Star Wars score analysis too.

I do video production work now, but in a past life I majored in theory and composition, and I occasionally delve back into that world. Your analysis of film music is a great way to bridge the two main creative worlds that I’ve inhabited in my adolescent and adult life, and you do a great job breaking things down for my now-long-out-of-practice analytical ear. Really excellent work!

Thank you, Steve! It’s always rewarding to hear that the work I do connects with others and offers them something they appreciate. Cheers.

Hi 🙂 Awesome, just awesome!! 🙂 I cant describe my coming euphoria while I was reading the text. :)))

To be honest, so far I have thought John Williams had everything (melody, etc) in his head and he just put it in a paper and well, it is done! 😀 But as I can see, a music composition is just like math :O

Or am I wrong? How does he compose music? He just closes his eyes, thinks about “scene” and a melody will just appear out of nowhere or he sits in front of his piano and mechanically tries to find the right tones to fullfil his imagination of f.e. “brave theme” or “fight theme”?

Hi Maroš. Thanks for your enthusiasm about the analysis! I can’t say I know how Williams comes up with his music, but I will say it has a lot to do with improvising at the piano. Remember that when he first came to Hollywood in the 50s, he was a jazz pianist who played in films and for recordings of film and television music. So I think a lot of what he writes comes from playing it at the piano, but I think for the themes, he probably composes those mostly in his head since he talks about writing all his themes before composing the whole score. And he often takes a very long time to polish them into their final form, so I imagine he ponders them away from the piano for quite some time.

As for writing themes that sound like “bravery” or “fighting”, well, that’s one of Williams’ gifts as a composer and something I’ve tried to show in my posts here as to why they sound so perfect for the things they represent. But how he comes up with it is probably very second-nature to him, in other words, it’s not mechanical but something that just sort of happens for him. That’s my guess, anyway.

Any new, particularly memorable leitmotif or theme that appears in “The Force Awakens” next year…Please remember to analyze it – I’m sure there would be many who would like you to.

Thanks, Tomer. No worries – I’ll be all over that score! I’m very interested to hear what Williams does with it and to see the film he has to work with. Cheers.

First rate analysis–really terrific explanation for a layman or a musician to enjoy. Would you agree with other annotators that there is a strong resemblance in the opening 4 or 5 notes of the main theme to Korngold’s Kings Row main title? Given Williams’ stated admiration for Korngold it would not be surprising to find a conscious or unconscious tribute there. Anyway, it is wonderful to see someone take a serious approach to this particular art form.

Thanks, David! I always appreciate knowing how these posts come across to those who enjoy film music but may not have a lot of formal training.

Absolutely, I would agree that this theme resembles Korngold’s to Kings Row, and I very strongly believe it is entirely conscious and intentional. After all, Lucas has said outright that what he wanted from the get-go was a Max Steiner type of score, so the old Hollywood scores were directly being channeled, and certainly this was Williams’ way of doing that. In short, the music of Star Wars was very strongly shaped by George Lucas. That’s why so many cues have these kinds of resemblances. Many people believe that Williams is a musical thief who plagiarizes well-known classical works as a way of ensuring success, but nothing could be further from the truth, as the story behind Star Wars tells so clearly.

Thank you so much for this wonderful analysis of Williams’ themes. I’m an elementary music teacher who is working on a unit on movie music for my 5th graders. I wanted to illustrate the importance of the leitmotives in the process of storytelling within these movies, and your site is a priceless resource. Thank you!

Thank you, Beth, for the kind words. I’m delighted to hear that you’re teaching film music to young minds. With the associations music is given in film, I think it makes abstract classically-based music easier to understand for children and, indeed, for anyone! Kudos.

Thanks for your analysis. As one who doesn’t know how to read music, some of it is over my head. I haven’t read all of your pages, but I’m looking for more info on the SW music ‘cues’ – classical and film selections that Lucas says he wrote sections of the screenplay to. He mentioned Korngold in interviews, so the Kings Row Fanfare was either listened to or Lucas guided Williams to it. But so many other themes are obvious – Darth Vader theme to Funeral March by Chopin (Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 35, in B-flat Minor) and Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges March for Ewoks, etc; Lucas has said he wrote SW listening to music fitting the scene, and seems to have passed these on to JW, who used some if not all of them, as springboards. Do you know where more has been written on this connection to classical/film music motifs that JW started from?

Yes, check out J. W. Rinzler’s The Making of Star Wars, which discusses some of the classical pieces and film cues that were used in the film’s temp track and ultimately had a large part in carrying over to many of the original film’s cues.

Boa análise. É claro que tem um ponto esquecido que é ao meu ver fundamental. Holst, Gustav Holst, sem ele meu caro, Mr Willhams não seria nada. É só ouvir a suite Os Planetas, especialmente Marte o planeta da guerra.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHVsszW7Nds

Good analysis. Of course it has a forgotten point that is in my view essential. Holst, Gustav Holst, without he my dear, Mr Williams would be nothing. Just listen to the suite The Planets, especially Mars the planet of war.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHVsszW7Nds

Thank you, Manoel. Yes, I am aware of the influence of Holst’s Mars on the Star Wars score, but I don’t believe it has anything to do with the film’s main theme. It’s most evident at the end of the main title cue (not the theme itself) when the ships appear onscreen, and also at the end of the film in the lead-up to the destruction of the Death Star. But I respectfully disagree that Williams would be “nothing” without the Holst influence. Yes, there are several moments in the score that are heavily tied to other pieces but that’s because Lucas wanted it that way. And besides, these references we hear to other pieces are but short moments in a huge score. It would be impossible to claim that the score is “just a lift” from classical models as the vast majority of the score is composed without such references.

Hi, thanks for the great analysis. I would like to know your thoughts on the melody changing to a minor scale at the end, descending from the root. I thought it was quite surprising when I first realized it. Then I found that some TV series openings do the same thing. Is there a name for this technique?

Hi Nils. That’s a great observation. I would say that, for themes in major keys, having the key turn minor is common just before an important arrival point, like the return of the main melody. Could you list some of the TV themes you have in mind? And actually, the Star Wars main title does this not only where you mention (I assume you mean in the B section just before the main theme comes back), but also just before the main theme enters for the first time. The scale flourish that leads into the theme is actually minor but when the theme comes in, it’s of course major.

This kind of minor-key preparation for a major-key theme happens all the time in classical music as well. It’s a bread and butter technique, whether it’s for moving from a slow introduction into the movement proper (very common) or preparing for an important theme in the movement itself, like before the so-called second theme in sonata form, or even more commonly, in the development section just before the return of the main theme at the start of the recapitulation.

how does John Williams suggest mysterious distant galaxies in the middle section and then the built up threat

Hi Jenny. The strangest thing about this middle section of the main theme is that Williams didn’t actually write it for the main theme! Check out this interview he did with the Pacific Symphony Orchestra, in which the maestro himself states that he wrote the middle section for the Throne Room melody, then used that for the middle section of the main title: https://vocaroo.com/856a8uo8HcN. There are also some musical factors supporting this as well, most of all the use of the same, or very similar, motives in the B section as in the Throne Room’s A section. Long story short, any associations we have of this music suggesting the distant galaxies and build up of a threat you mention are more because of the visuals its placed with in the main theme rather than inherently musical properties. Even so, it does work enormously well and it’s incredible to think he didn’t actually write it for the film’s opening!