Diamonds Are Forever (1971), the seventh entry in the James Bond film franchise, saw the return of Sean Connery in the lead role after George Lazenby’s only performance as 007 in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Also back was Guy Hamilton, who had directed Goldfinger and would go on to direct the next two Bond films after Diamonds. One might therefore think that Diamonds would largely continue the style of the first five Bond films, especially Goldfinger. This time, however, things were different.

Despite Jon Burlingame’s claim of Diamonds in The Music of James Bond that “the new film’s tone was much lighter than any previous Eon-produced Bond,” I argue that the tone of the film is actually a good deal darker through the more deliberate cruelty of the characters: Blofeld’s hired assassins, Kidd and Wint, carry out several murders with an unsettlingly disingenuous air; a gang member throws Plenty O’Toole out a high hotel window and admits he didn’t know she would land (safely) in a swimming pool; and even Bond himself adopts a more sadistic manner, in the opening scene choking a woman with her own bikini top, leaving her both bare-breasted and breathless. Clearly, Hamilton wanted to take the Bond series in a new direction despite having Connery back in the lead. Musically, however, their vision was not as clear. While it seems that John Barry sought to continue composing in largely the same vein as the previous Bond films, Hamilton and the producers did not always agree. The result is a score that remains oddly situated between the familiar and the unfamiliar, as we shall see in the following film music analysis.

The James Bond Theme

The first indication of the music’s return to the pre-Lazenby Bond sound is the scoring of the James Bond theme in the famous gun-barrel opening. In On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Barry replaced the electric guitar that plays the opening riff with a synthesizer, giving the theme a new sound to match the new face of Bond. But in Diamonds Are Forever, the theme reverts to the old guitar scoring last heard in You Only Live Twice:

With this familiar guitar sound, the music seems to signal that the film’s style is back in the world of the other Connery Bond films. Significantly, though, besides this gun-barrel opening and the immediately following precredit sequence, the riff is not heard in this way anywhere else in the film, Barry instead scoring it for the brass (when Bond leaves on the hovercraft to Amsterdam) or a more subdued high electric guitar (when Bond goes to Willard Whyte’s summer house, where he meets “Bambi” and “Thumper”).

The Title Song – “Diamonds Are Forever”

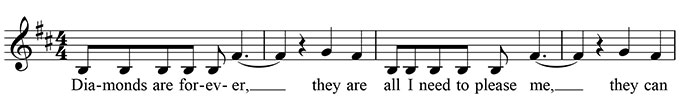

As with his use of finger cymbals in Goldfinger to suggest the gold metal in the film, Barry made a similar decision for his Diamonds score. The title song for Diamonds begins with an eight-note repeating figure, or ostinato, that serves as an accompaniment:

The figure is sounded by a particular electronic organ Barry came across at the CTS studios, where the early Bond scores were recorded. As audio engineer of the Diamonds score, John Richards recalls of Barry, “John used just one facet of that organ. That tinkly bright sound that you couldn’t get on anything else.” Hence, Barry conjures up an appropriately “sparkling” sound to suggest the precious gem in Diamonds. Hear this figure at the start of the clip below:

As with the previous Bond films, Barry’s title song for Diamonds is used throughout the film as a sort of main theme:

The accompaniment, for example, appears at several points in the film as a suspense or danger motif, but it doesn’t always occur in the same way. Although Barry generally retains its eight-note pattern, he changes the scoring of each consecutive appearance, keeping it sounding fresh. In particular, those appearances that are scored for the electronic organ are associated with a heightened sense of uncertainty in Bond, as occurs when:

- Surprisingly to Bond, thugs in his hotel room leave without discussing the diamonds (this appearance is actually combined with the glockenspiel, giving it a slightly harder sound)

- Bond and Tiffany Case follow Bert Saxby in his van to a mysterious and remote facility that they later discover is researching lasers for Blofeld’s satellite

- When Bond goes to and arrives at Willard Whyte’s summer house, Bond’s CIA accomplice Felix asks Bond if he knows what he’s doing, to which Bond responds, “ask me again in ten minutes”

Thus, the accompaniment’s scoring doesn’t just set the mood for the scene, it has a narrative function in suggesting Bond’s psychological state in those scenes.

Likewise, the song’s melody, which begins with a memorable hook of a rising fifth on the words “diamonds are forever”, appears at numerous points in the film, again as a sort of main theme. For example when Bond unexpectedly comes across Tiffany in his hotel room, the theme is heard in a luscious string arrangement that suggests a romantic encounter between the two.

But the title song and/or its accompaniment appear far less prominently in this score than in previous Bond scores because more room was made for numerous jazzy diegetic cues like “Q’s Trick”, which is heard inside a casino as Q manipulates the slot machines to his advantage:

As Burlingame notes, these cues comprise nearly a third of the sixty-seven minutes of music in the film. And this idea was tied to the soundtrack album, which United Artists Records believed would be more profitable with more jazz cues and less non-diegetic score. Thus, from the perspective of previous Bond films, Diamonds takes the music in quite a new and unfamiliar direction.

Other Themes

Kidd and Wint’s Theme

Mr. Kidd and Mr. Wint are given their own theme (or leitmotif), a stealthy, mysterious melody for the flute and alto saxophone that tails off into a glissando, heard at 0:10 in the clip below:

Recall in Goldfinger that Oddjob was given his own leitmotif. Hence, the technique of scoring the main henchmen of a Bond film with a leitmotif continues a familiar aspect of the older Connery Bond films.

The 007 Theme

Barry introduced this theme into the Bond franchise with the second film, From Russia with Love, as a theme to accompany some of the action scenes. Its upbeat rhythm is of course typical for this type of music, but it is unusual by being set in a major key, which lightens the tone of the music and, in turn, the scene onscreen. In Diamonds, the theme appears near the end of the film when Bond is on the oil rig, takes control of Blofeld’s escape pod with Blofeld inside, and proceeds to thrash it about:

Certainly, the use of this theme creates a strong link with the other Connery Bond films, not only From Russia with Love, but Thunderball as well, where it is heard during the climactic underwater battle. But at the same time, its use in Diamonds is an unusual bit of levity within an otherwise more serious Bond film.

Sparse Music in Action Scenes

Perhaps the most conspicuous difference between the use of music in Diamonds as compared to its predecessors is the sparse music in fight and chase scenes. While music generally does make an appearance in such scenes, it is only after an ample portion of the scene has passed completely unaccompanied. Examples are numerous:

- The elevator fight between Bond and smuggler Peter Franks

- The moon buggy chase

- The car chase in Las Vegas

- Bond climbing the wall of the “Whyte House” hotel

- The final battle on the oil rig

In feature films, one of the functions of music is to provide a signal that what we are watching is a work of fiction. Generally, the more unreal a film is, the more music is required to draw us in, allow us to suspend our disbelief, and experience the characters’ fictional world vicariously. In the absence of music, the situations in the film become much more real, as though we are watching a portion of a documentary film. This shift towards reality lends the film more gravitas and creates a more serious atmosphere. In the previous Bond films, action scenes such as this are usually more completely lined with music (unless the sound effects are the focus of the scene). The particular “spotting” of music in Diamonds (i.e., the decision of where to place music and what kind to use) is therefore quite an unfamiliar element in the film.

Ostinatos

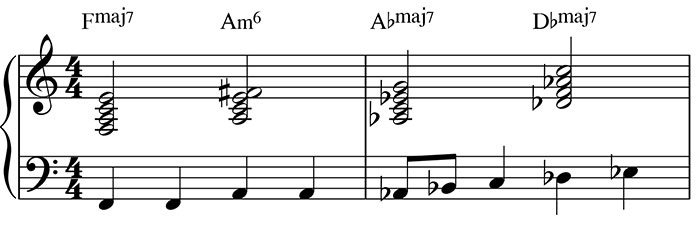

As with the previous Bond scores, Barry uses several ostinatos throughout the film. Kidd and Wint’s theme, for instance, is usually heard with a plodding ostinato accompaniment. But the most prominent ostinato in Diamonds is surely the four-chord progression associated with the launch and operation of Blofeld’s diamond-studded laser-beam satellite, which carves a destructive path across the globe, heard in the clip below from 0:20:

This memorable ostinato forms an especially strong connection to You Only Live Twice, which features a “Space March” that likewise is associated with a spacecraft and occupies a similar soundworld:

Conclusion

Despite the return of Sean Connery as James Bond, Diamonds Are Forever sharply diverged from the previous Bond films as its tone was noticeably darker. And yet, the director and producers of the film seemed to be ambivalent about the direction the music ought to take. Barry seemed adamant to retain more of the established musical style of the Bond films than he was allowed, the best example being the moon buggy chase, for which he actually wrote a dramatic cue in the manner of previous Bond films. But since the scene begins with the filming of a falsified moon landing (a joke that refers to conspiracy theories about the 1969 American moon landing being a fraud), the filmmakers believed a more comical type of music to be more appropriate. Barry ended up writing something in between—light, but not necessarily comical. The result is a cue that begins with a hesitant sound that feels shackled, as though it wants to burst out into something more intense, which it only does later in the scene. What is remarkable is that, despite these inconsistencies in the filmmakers’ vision for the film, Barry was still able to come up with one of his best-loved scores in the James Bond canon.

Coming soon… Moonraker.

yet another great post. Some of my fav Barry music. The theme to Mr Kidd is especially good. Lovely sound flute and sax mixed together. Please do You only live twice too !

e

“Significantly, though, the riff is not heard in this way anywhere else in the film”

Actually, it is: just after Connery is shown on-screen saying “My name is Bond…” and strangling Marie with her bikini top.

Hi g’per – you are correct about this. I suppose I would understand this extra statement as an extension of that in the gun-barrel sequence since it directly follows that, where we just heard the guitar riff. I’ve updated the text above to reflect that. Thanks for pointing it out. 🙂

You’re welcome- and yes, you could consider it an extension even though they are 2 separate cues expertly (as usual) overlapped at about the 20 second mark.

Looking forward to Moonraker.

Hi Mark,

I was wondering if you analysed film music for cartoons? Like Inspecter Gadget?

Hi Tuan – I haven’t yet analyzed cartoon music, but I do have an interest in it and think it is a neglected form of music simply because it’s not “serious” music in the way, say, most film music is. But I have done a bit of transcribing of Carl Stalling’s music for the old Warner Bros. cartoons. Now that man was a genius when it came to writing cartoon music. Thanks for the suggestion – I’ll put it on my “to do” list.

Hi

I have been struggling to work out the chord sequence for ‘007 and counting’ (the laser in space sequence) for years – so thank you for the tantalising snippet you’ve provided! Is there any chance of a providing more of the score or do you know where else it can be obtained?

Julian

“007 and Counting” is a very attractive progression, so I thought it deserved being spelled out. I just did it by ear because I don’t have a score, nor do I know where one could be obtained. But if you have particular chords or progressions you’d like me to have a crack at, let me know.

Thanks for the response, using your chords as a starting I think I should now be able to work out the rest – much appreciated and very much enjoy your informative posts.

My great thanks for your site and this analysis. I am a film critic and have loved DAF as an example of a film that does not follow the tradition of the films that preceded it (in a sense it fails as a traditional James Bond movie, but succeeds in this failure). The movie stakes out an original position and trajectory for the series, but one which is lost when Roger Moore takes over (I am not sure it was sustainable under any circumstances).

The score has always stayed with me (though I am not particularly musical) and the theme song is my favorite. Your explanation of how the score works has helped me a great deal in my work on the film. Any of my writings on the film will certainly include reference to your work and site which is most valuable for a film scholar such as myself who is more visually oriented than musical.

Thank you again.

Thank you, Brian, for your words of praise. I do what I can to contribute to the small but growing literature on the analysis of film music. I’m glad you found my remarks helpful. This is one Bond film in which I didn’t agree entirely with Burlingame in his book on the Bond scores. I find it an awkward score for an awkward film, and I think Barry’s frustrations attest to that to some degree. But then, I approach it from a musical point of view, so I’d be interested to hear more of your point of view. Perhaps you could send me a link to your work if you decide to write on it sometime. Cheers.