On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, released in 1969, was the sixth film in the James Bond franchise, and the first not to star Sean Connery as 007. With Connery having become so strongly associated with the character, his replacement, Australian model George Lazenby, certainly had big shoes to fill. As the film’s composer John Barry himself admitted, he had

“to make the audience forget that they don’t have Sean. What I did was to overemphasize everything that I’d done in the first few movies, just go over the top to try and make the soundtrack strong. To do Bondian beyond Bondian.”

So how does one “do Bondian beyond Bondian” exactly? As Jeff Smith points out in The Sounds of Commerce, “producers Harry Saltzman and Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli have frequently acknowledged the importance of a consistent formula to the durability of the series,” part of which is the music. And indeed, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service makes a concerted effort to forge deliberate links with the previous Bond films. In the title sequence, for instance, brief clips from the five previous films are shown behind the credits. And when Bond has supposedly resigned from the secret service, we hear snippets of themes from the previous films as he looks nostalgically at the trinkets he has collected from the assignments in those same films. With Honey’s belt and knife, we hear “Under the Mango Tree” from Dr. No; with Grant’s garrotte-watch, we hear “From Russia with Love”; when Bond looks at his own miniature underwater breathing apparatus from Thunderball, we hear the title song of that film. And when Bond is taken by force to see Draco, the caretaker whistles the tune to “Goldfinger” as he sweeps the floor.

Naturally then, in his score for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Barry uses many of the same techniques as he did in his previous Bond scores, including those we saw in his score for Goldfinger. But he also includes new elements that serve to distinguish this score from the previous films and give it an appropriately fresh sound that matches the fresh face audiences were now seeing in the role of Bond. Below I give a brief film music analysis demonstrating how the score fuses both the old and the new with this extra emphasis on the new.

The James Bond Theme

The first new musical element of Barry’s score is the replacement of the guitar riff in the James Bond theme with a Moog synthesizer, which occurs in the gunbarrel opening, the precredit sequence, and the end credits. Here it is in the first of these:

As Jon Burlinghame notes in his book The Music of James Bond,

“The film’s release in December 1969 marked the first time any major studio had featured the synthesizer so prominently, and at the same time fully integrated within the traditional orchestra. It wasn’t just trendy; it was a groundbreaking application of electronic music that would presage decades of synthesizer use by film composers everywhere.”

Thus, from the start, and even before we see Lazenby as Bond in the film, the music alerts us of a striking change to the film’s style and does so in a way that, like the very choice of Lazenby, is something of an experiment.

The use of the Bond theme is also downplayed more than in the previous films. In large part, this has to do with the fact that the theme is not incorporated into either the film’s title piece or main song (“We Have All the Time in the World”) the way it was in Goldfinger (and Thunderball as well).

There are a few times the Bond accompaniment alone is heard, as when Bond has what he thinks is his request for resignation signed and returned to him by M, or when Bond first meets the young women being trained as Blofeld’s “angels of death”. We do hear the older guitar-riff version of the theme when Bond and Draco come to rescue Draco’s daughter Tracy from the hands of Blofeld, but, significantly, this was director Peter Hunt’s decision, not John Barry’s. For Barry then, it seems that the new face of Bond required toning down the reliance on the Bond theme.

The Title Song

Although, like the previous Bond films, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service provides a memorable popular theme with the main titles, it is one performed instrumentally rather than vocally, something that had not been done in previous Bond films. (In Dr. No, there is an instrumental portion in the main titles, but it is strictly a percussive rhythm and not a theme). Like the Bond theme, Barry’s title theme, simply called “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”, makes use of the Moog synthesizer, only in this case, we hear it as part of a march-like four-note accompaniment figure:

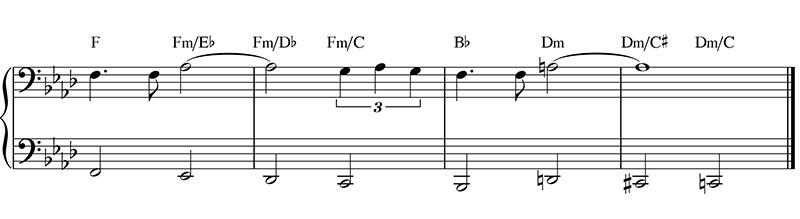

The theme’s melody begins with a dark colouring in the trombone and is supported by some quirky changes of harmony that give the theme a distinctive sound:

Here’s the theme as it appears in the main titles (with its introductory chords):

After these main titles, the theme disappears until the ski chase of Bond by Blofeld and his men roughly an hour and a half into the film. From this point on, Barry makes heavy use of the title theme to score the several intense action scenes in the latter portion of the film. While it may seem strange to hold off on repeating a theme for such a length of time, Barry’s decision is quite effective for at least two reasons. First, most of the film’s score contains not the title theme, but the film’s vocal song, “We Have All the Time in the World”. Given that this film is one of the longer Bond films at 142 minutes, the shift in focus from the song to the title theme provides a welcome sense of musical variety. And secondly, this shift occurs just as Bond is escaping from Blofeld in the ski chase, which sets into motion the series of action scenes that are the climax of the film. Thus, the change in the music’s intensity from the romantic sound of the song to the march-like title theme is also well coordinated with the events in the narrative.

“We Have All the Time in the World”

The film’s main vocal song, “We Have All the Time in the World”, composed by Barry and performed by the inimitable Louis Armstrong, appears not with the main titles, as is typical of Bond films, but with a montage of Bond and Tracy’s blossoming romance:

While not exactly a leitmotif, the song appears in instrumental form throughout most of the film in relation to Tracy and Bond together (mostly as a love theme), as when:

- Tracy confronts Bond after he fights off an intruder in his own suite

- Tracy and Bond arrive safely in a barn, where they spend the night

- Bond caresses Tracy after she is shot by Blofeld and Fräulein Bunt

The song is also used to refer only to Tracy on her own, as when she is seen driving to see her father on his birthday, or, indirectly, when her father is telling Bond about Tracy’s upbringing. But there are other appearances of the song that do not relate to Tracy or her relationship with Bond, as when Bond is taken by gunpoint and knifepoint to Draco (from 0:11 below):

Notice, however, that before the melody comes in, we hear a four-beat accompaniment that sounds much like a major-key form of the accompaniment to the march-like title theme we saw above, now even with snare drum added. We hear this form of the song in several scenes, for example when:

- M relieves Bond of “Operation: Bedlam” (that is, to catch Blofeld)

- Bond explains the procedures involved in attempting to locate Blofeld through his genealogical request to the London College of Arms

- Bond arrives at Piz Gloria, Blofeld’s mountain-top lair (Piz Gloria)

- Bond inspects the room he has been shown to at Piz Gloria

In each case, the focus is on Bond in a situation where he is not in immediate danger (even his forced taking to Draco is for Draco’s benign purposes). In this way, the song sometimes functions as a theme for Bond—a substitute for the James Bond theme. After all, in From Russia with Love, we hear the full James Bond theme while Bond inspects the hotel room he has been shown to, in just the same way he does in the scene above. Hence, as with the “Goldfinger” song in that film, “We Have All the Time in the World” sometimes functions as a leitmotif, but is more accurately described as an overall main theme for the film that may be transformed to accommodate various characters in various situations.

The “Sexy” Theme

Barry introduces a new theme for Bond’s encounters with the young women at Piz Gloria who believe they are being treated for their allergies, all of whom just happen to look like models. This theme is heard when Bond is first introduced to the women and when he is acting on one of the women’s invitations to a nocturnal tryst. On the other hand, it is also heard whenever one of the women is attempting to seduce Bond. Thus the theme, which might well be called the “sexy” theme, signals not only Bond’s attraction to the women, but also the women’s strong yet playful attraction to Bond (disguised as the genealogist Sir Hilary Bray). To give it this playful, sexy air, Barry scores the theme for a quartet of alto saxophones plus violins and writes a mildly dissonant pair of major-seventh chords in F major (BbM7 and FM7) that are repeated:

The opening upward leap in the melodic line also helps convey the almost electric sense of attraction the characters feel upon seeing their object of desire.

Ostinatos

As in Goldfinger, Barry makes use of several ostinatos in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, usually to create a suspenseful mood. For example, when Bond goes to the office of Blofeld’s lawyer, Gumbold, and breaks into his safe in search of Blofeld’s current location, we hear a two-phrase ostinato in the piano, timpani, and low strings:

Hear this from 0:05 in the clip below:

As time begins to run out for Bond in the office of Gumbold (who will soon return), Barry adds a melodic line in the synthesizer overtop of the original ostinato that reiterates the “newness” of this particular sound in the Bond series and heightens the tension of the scene (listen to the clip below from 1:05):

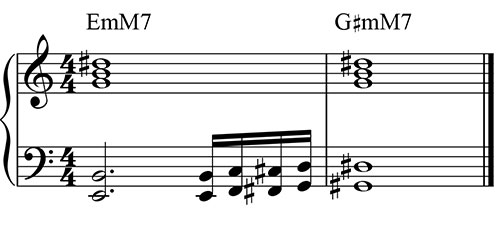

Another prominent ostinato in the score is one associated with the mind-control of the young women. Like the “sexy” theme, this ostinato is based on a slow progression of only two chords, a pair of minor major-seventh chords (a particular favourite with Barry), or EmM7 – G#mM7 (hear this in the clip below at 2:36):

These two chords are connected through a series of parallel fifths rising chromatically, which are suggestive of something done in stealth. (Note that the same technique appears in Henri Mancini’s theme to The Pink Panther, which he wrote to suggest the stealthy nature of the jewel thief known as “The Phantom”).

Conclusion

As we have seen, John Barry fuses both old and new techniques in his score for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. On the one hand, the general components of the score remain largely in the same vein as the earlier scores—the use of the title theme and vocal song (which are separate in this case) as main themes, the incorporation of the Bond theme at the beginning and end, and the employment of other themes and ostinatos unique to each film. On the other hand, the particulars of each of these components are altered, from the use of the Moog synthesizer in the Bond theme (and throughout the score) to that theme’s decreased presence in favour of the two main themes of the score, even to the extent of using a main theme where, in earlier films, we heard the Bond theme. In that sense, while Barry remained true to the ingredients of a Bond score, he altered their proportions so that there is more emphasis on the new additions to the score than the familiar old ones. In other words, he expanded the boundaries of the traditional Bond score. Perhaps this is what Barry meant by doing “Bondian beyond Bondian”.

Coming soon… Diamonds are Forever.

What a great study, Mark! All I am missing is possibly an analysis of Barry’s Christmas music that I find very characteristic of the film (‘Do You Know How Christmas Trees Are Grown’ and its derivatives, the ice rink waltz etc). Great work!

Many thanks, Daniel. I quite enjoyed going through these scores. There’s just so much there to talk about. Yes, I thought about the Christmas music, which people seem to either love or hate, but wanted to keep the post on the shorter side of long. Thanks for your comment!

I understand, Mark. You have to set your limits. 😉 To me the Christmas music in the film is so crucial to its very unique atmosphere – a sense of danger and threat to Bond, but at the same time it is played out during the most festive times. In that way, I think the film singles itself out from the other Bonds in the canon. Furthermore, that they had Barry write original Christmas music for the film rather than using any source music contributes even more to this perception. 🙂

I have very much appreciated your analysis of this terrific score and how Barry succeeded in

Anchoring this movie in the Bond universe despite it being so far removed from the well trodden and understood formula.

Apart from Connery’s superman portrayal being absent so were the overblown sets, camp humour, over elaborate gagets and self parody. Instead the audience wss presented with a Bond who was flawed who fell in love had self doubt and vulnerabilty.

You have explained extremely well how Barry adapted his traditional style to emphisise this “NEW CHARACTER” is still James Bond but you omitted some other cues such as the fight section of This never happened to the other fella that is nothing like what has gone before. I recall when i first saw the movie getting to my seat late i wasn’t sure it was a bond movie on the screen because the music sounded so un bondian.

Also how short passages of underscore such as the drive to M’s home which reinforces the title theme yet gives a sense of melancholy that subtlely conveys that this character might not be as confident as the full main title theme would suggest.

I would contend that not even in the Dalton TLD and the Craig movies where Bond often wears his heart on his sleeve does the audience really feel Bond is sincere in his antipathy to his job and his life without HMSS.

It is of course Lazenby’s interpretation that should take a lot of the credit but also Barry’s contribution cannot be underestimated.

Another example which set the tone of the movie musically is in This Never happened cue when Tracy roars away in her Cougar where the music instead of being up beat into the titles ends in a most mournful manner preluding Bond’s loss at the movie’s end.

In many ways this score was too good and indeed maybe the whole film was too good to be a Bond movie.

Do you agree?

I would really like to read your opinion on the cues Try, Over and Out amd The More Things Change.

Hi John. Your comments are spot on and I agree entirely. As for the cues I didn’t discuss, about the beach fight I would say that it is an ostinato based on four chords, all of them minor major-seventh chords (a Barry favourite). It doesn’t represent anything specific, it’s more just intense music meant for a fight or chase. In fact, I could imagine how Barry might have used, say, the title theme score for the scenes where this music appears.

I’ll have to look over the other cues you suggest again very soon, probably by end of week. Thanks for your very thoughtful comments.

Superb article and enjoyable read; my question is simple: does anyone know what that piece of music is that is played in the background at the end of the ski-chase (first one where Bond escapes Piz Gloria) and during the chase on foot through the village? Not the song “Do You Know How Christmas Trees Are Grown?” (which I also like), but the instrumental piece.

Oh and a piece of trivia: when Bond throws one of Blofeld’s henchmen over the cliff prior to this scene and the man’s cries are heard as he is falling to his death, these same cries appear at the end of a song released by a group called Edelweiss in 1988 called “Bring Me Edelweiss.” (At least I’m 99% sure that’s correct!)

Hi Peter, thanks for your keen insights. I don’t know what piece that is playing behind the end of the ski-chase. It sounds like a traditional march of some kind that moves into a waltz-like theme when the scene moves into the crowds in the village. Not sure if they’re part of the same piece or are two different pieces.

Fascinating about the “Bring Me Edelweiss” song. It seems that they simply lifted the scream from the Bond film, because the same source music (the traditional march or whatever it is) is heard behind the scream once it fades away, in exactly the same manner as in the Bond film. No idea why they’d do that, but that’s very much what it seems like.

There’s an interesting quote from a late 90s interview with John Barry about Bond and Tracy’s relationship in the film:

That was another “first time” problem—a new face! To help the audience through the change, the entire opening sequence is very tradition-heavy. It establishes everything that had gone before, everything that was very “Bondian.” The movies before it always moving away or moving ahead, but this was a giant step back, as if to say, “Listen folks, it’s okay, this is James Bond, James Bond,

James Bond.” There were first-class action sequences in that movie, technically. Also the song was a new idea that I liked. That movie didn’t move you as it should have done when she dies at the end. The chemistry just didn’t work. I wrote what I thought was one of nicest songs I’ve ever written, “We Have All the Time in the World.” I wanted it to work like “September Song.” I wanted the irony of an old man singing around this young girl’s death—and that’s why I wanted Louis Armstrong. I could think of no one else but Louis Armstrong from the start…..

When I went to them and asked, “How about Louis Armstrong?” they were surprised, they weren’t sure what to say and asked why. I explained my reasoning, and they said, “Great.” If that same theme had been for Sean Connery and a really great Bond broad, for want of a better term, it would been an entirely different picture! I hate to use the words, but it’s like “shovelling shit against the tide” when you feel a strong chemistry by reading the script, but on screen it’s just not working. You can play just about anything against it—you can play Rachmaninoff, you can play a Bartok piano concerto—but you’re still not going to get anywhere emotionally because it just does not work. When directors say, “This isn’t really working here, but once the music is over it . . .” I say, “Wait! No, no. It actually makes it worse.” And, in a strange way, it actually does make it worse because the audience subconsciously senses a cover-up. They know it’s not working, they know you’re attempting to cover up for what’s missing between the actors. It almost makes it laughable, it almost becomes a parody or a send-up.

Its quite astonishing looking back at the film now and feeling this way about it, clearly he didn’t feel the performance worked between Lazenby and Rigg. But was being so close to the production and knowing the problems, swaying his thoughts?

This makes me wonder if Barry had ever revisited the films he worked on at later dates and whether his views may have softened or whether he is recalling memories from the actual time? For many of us that have seen the films countless times, if we didn’t think much of it initially, more often than not our appreciation for them can grow.

My feeling is, being a busy and active composer, he did not have the opportunity, or was particularly interested in going back over them so we are left with his initial thoughts.

That’s a very interesting reaction from John about the “lack of chemistry.” Do you know for whom or what this interview was for?

This is Wonderful!!!

Very interesting article, and series of articles. I, too, think we underestimate the value of “Do You Know How Christmas Trees are Grown?” The song is so sickly sweet and cheery, with the vapid boys’ choir, that it takes on a sarcastic tone in the context of a man hunt, training girls to be angels of death, Blofeld’s vain and selfish aspirations…. The wowzer for me is that when Bond is being run to ground, hiding in the Christmas celebratory crowd, tired, alone, and clearly running out of options, the words, “… they need LOVE” reach a crescendo as Tracy skates up to Bond, and we have a marvelous reveal of Diana Rigg. I have a hard time thinking it’s an accident, I’m convinced that Barry and director Peter Hunt meant this to play out. It’s sometimes offensive when the score underlines the plot so boldly, but in this case, it makes it an ever greater emotional moment.

Thanks for a great analysis of a great film score.