While the first two James Bond films, Dr. No and From Russia with Love, were profitable enough to spawn sequels, the third—Goldfinger, released in 1964—was the first massive Bond hit. The film’s soundtrack was a huge success as well, selling 400,000 copies within five months of its release and earning $1 million in sales to reach the status of, appropriately enough, certified gold. As the film’s composer, John Barry, claimed of the film’s music, “everything came together, the song, the score, the style.” It is the style of the score that I will examine in this post, breaking down several of Barry’s compositional techniques in a film music analysis.

The “Goldfinger” Song

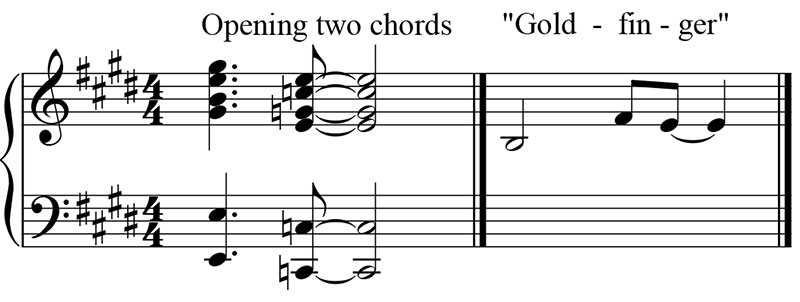

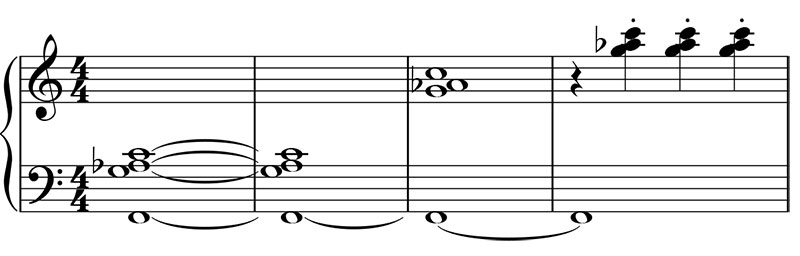

The music of Barry’s score is highly unified because it derives almost entirely from the “Goldfinger” song played with the main titles:

In this way, the score may be considered a “theme score”, which, in her book Settling the Score, Kathryn Kalinak defines as “a stylistic approach to film scoring which privileged a single musical theme.” This practice certainly wasn’t new with Goldfinger—twenty years earlier, David Raksin had used the same technique in the classic film noir Laura, the title song of which became an unexpected pop sensation when it was set with lyrics.

But in the 1960s, production companies actively sought out pop-style title songs for their films that could be marketed to the burgeoning youth audience and, with any luck, become a hit. Thus, as Jeff Smith points out in The Sounds of Commerce, “songs like ‘Goldfinger,’ ‘Moon River,’ from Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and ‘Lara’s Theme (Somewhere My Love)’ from Doctor Zhivago (1965) were amply repeated within their respective films in order to strengthen their prospects as commercial singles.”

All this is not to say that Barry’s score is somehow devalued in light of this financial concern for his music. On the contrary, the score works incredibly well, partly because of Barry’s skill in manipulating the same basic material to express a variety of moods, and also because Barry cleverly includes quotes of the James Bond theme within the Goldfinger song, providing a way of suggesting Bond even while using the Goldfinger song’s material.

Uses of the Goldfinger Song/Theme in the Film

Most obviously, the material of the Goldfinger song functions as a sort of leitmotif for Goldfinger himself, as is made clear when we first see the character at the Miami Beach hotel at the film’s beginning. Throughout the film, Barry draws mainly on the song’s opening two chords and the melodic figure set to the word “Goldfinger”:

But more typically, the song’s material works as a general main theme for the film, not necessarily suggesting the Goldfinger character. For example, when Bond drives through the Swiss Alps following Goldfinger, we hear the theme scored lyrically with the melody soaring beautifully in the violins, heard in the following track from 0:13:

Of course, Goldfinger himself is a part of the scene, and so the theme in part represents that character. Yet at the same time, the beauty of the music is also suggestive of the visual spelndour of the alpine landscape and, a little further into the scene, perhaps something of Bond’s romantic attraction to Tilly Masterson, who zooms past his car in a convertible, and of whom Bond says to himself “discipline, 007, discipline” (recalling his promise to M not to get involved with women on his assignments).

There are, however, many instances in the film when the Goldfinger theme is heard but the character is not seen. When Bond escapes from the cell at Goldfinger’s farm by duping the guard into entering the cell, we hear the three-note motive that is sung to the word “Goldfinger” in the song (played twice between 1:45 and 1:57 in the following track):

This would seem to be the perfect place to sound one of the motives from the James Bond theme instead, given that the focus is on that character and his success at this moment. But since this is a “theme score”, Barry’s use of the Goldfinger theme here is more as a main theme for the film than as a leitmotif for Goldfinger. Besides, it’s not as if Barry simply repeats the theme as it was in the song. The key is now minor, and most importantly, the scoring is very light, with a sustained string chord accompanying the theme played delicately in the harp. Thus, the music has an ominous quality that suggests that, even though Bond has managed to escape from his cell, he is not out of the woods just yet—indeed he’s still inside one of Goldfinger’s buildings and is captured again a short time later by Goldfinger’s collaborator, Pussy Galore. Barry therefore manages to capture an appropriate mood for the scene through a variation of the film’s main theme.

Other Themes in the Film

The James Bond Theme

Outside of the gun-barrel sequence that starts the film, there is very little use of the famous James Bond theme as an independent piece of music in Goldfinger. (In fact, besides this opening sequence, the guitar riff doesn’t appear in the film at all.) Rather, as noted earlier, Barry incorporates parts of it into the main theme, thus cleverly allowing himself to draw on Bond’s music in cues supported by the Goldfinger theme:

Most appearances of the Bond motives occur in this way. As with the main Goldfinger motives (the opening two chords, and the three-note “Goldfinger” figure), not all of these appearances of Bond’s motives are coordinated with a focus on the Bond character. Sometimes they are merely sounded as part of the film’s main theme and therefore contribute to the overall mood (in addition to signalling that this is a Bond film).

At other times, however, they do have a more specific meaning. For instance, after the golf game in which Bond unscrupulously beats Goldfinger, the Goldfinger theme begins in a light-heared vein. Then when Oddjob is loading the clubs into Goldfinger’s trunk and Bond tosses the homing device into it, we hear the portion of the Goldfinger theme containing the Bond accompaniment. Given the circumstances at this point, the Bond music emphasizes the twofold victory for James: first in winning the golf game, and second in tracking Goldfinger’s movements with the homing device. View the scene here:

Oddjob’s Leitmotif

Barry also created a leitmotif for Goldfinger’s mute henchman, Oddjob, that incorporates the unique sound of finger cymbals. As Barry explains,

“You hear it the first time you see Oddjob. I wanted the sound of metal, and finger cymbals are very small but they have a distinctive ‘ting’ sound—it was the whole idea of metal, of gold and the hardness of it.”

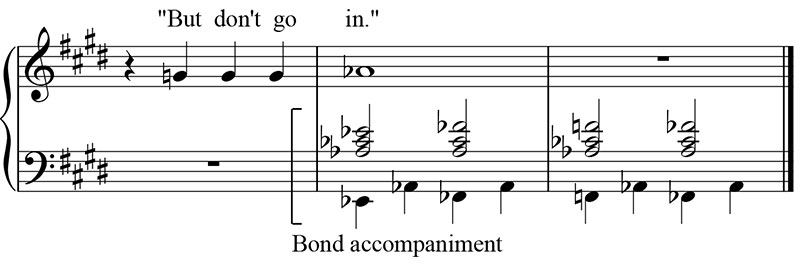

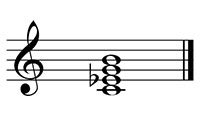

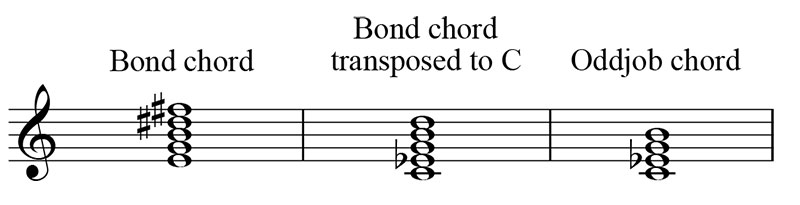

Harmonically, Oddjob’s leitmotif consists of a single sustained chord known as a minor-major seventh chord, that is, a minor chord with a major seventh added to it, a chord Bernard Herrmann made frequent use of in his Hitchcock scores (and hence Royal S. Brown dubs it Herrmann’s “Hitchcock chord”). With Oddjob, the chord is consistently C-Eb-G-B, or CmM7:

Because this chord contains the striking dissonances of a major seventh (C-B) and an augmented fifth (Eb-B), the resulting sound is full of tension and has quite an ominous ring.

We first hear the leitmotif when Oddjob’s shadow projects onto the wall after he knocks Bond out in the hotel room in Miami, thus clearly associating the leitmotif with the character. But the leitmotif is also associated with the terror of facing Oddjob’s deadly hat. Notice that the leitmotif appears when the tables are turned on Oddjob and Bond prepares to throw the hat at Oddjob in the duo’s fight scene at the end of the film (in the following clip at 3:50):

Ostinatos

When a major theme is not being sounded in the film, Barry often turns to the musical technique of ostinato—the repetition of a relatively short motive or phrase. Several of these ostinatos are based entirely on a single chord. For example, when Bond discovers Jill dead and painted gold, an E minor chord supports the ostinato melody. And when he is captured outside Goldfinger’s smelting plant, the ostinato is on a C minor added sixth chord (or Cm6), C-Eb-G-A:

Despite the simplicity of this technique, it can be enormously effective, as discussed below.

“The Laser Beam”

This is the famous scene in which Goldfinger has Bond splayed out on a gold platform with a laser beam inching ever closer to his groin. Like many other ostinatos in the film, it is based on a single chord, this time an F minor chord with an added second (or Fmadd2), F-G-Ab-C. Barry states the chord, then repeats its top three notes an octave higher, then three more times in a faster rhythm another octave higher:

Then the pattern starts all over again. Near the end of the scene, as the laser nears Bond, Barry adds a new repeating eight-note melody overtop of the ostinato that is half the length of the ostinato, thus raising the tension in the music and the scene. Then as the laser gets uncomfortably close to Bond, Barry shortens the new melody to just two notes repeating over the same ostinato—the tension has risen once more, and this time the melody’s insistence drives towards an impending resolution to the scene that keeps us on the edge of our seats. Just in the nick of time, Bond convinces Goldfinger to keep him alive and shut down the laser, at which point the ostinato finally breaks off into a fading sustained chord, releasing the tension built up throughout the scene. View it here:

The Unity of the Score

Barry’s Goldfinger score hangs together remarkably well. Of course, this being a theme score, the frequent use of the Goldfinger theme is a large part of the explanation. But Barry went further to ensure the unity of his score.

As noted earlier, the Goldfinger theme contains statements of the Bond accompaniment. But even in the pre-title sequence where the Bond theme is played on its own (since we have not yet been introduced to the Goldfinger character), some of the melodic figures heard over the Bond accompaniment sound an awful lot like Goldfinger’s theme, as if to suggest the intertwining of the two themes to come. In the following clip, the Bond theme begins at 1:11 and the Goldfinger-like figures occur at 1:25 and 1:28:

Furthermore, Oddjob’s major-minor seventh chord is actually contained within the opening chordal blast of the James Bond theme. The first chord of that theme is a major-minor seventh with a ninth added, or E-G-B-D#-F#, what could well be called the “James Bond chord” since it also memorably ends the theme on the electric guitar. Oddjob’s chord, then, can be formed by taking the first four notes of the “James Bond chord”, transposed to C as C-Eb-G-B:

Subtle as this may be, it gives the score a subconscious sense of unity, that Oddjob’s chord just somehow “fits” with the rest of the score.

Finally, many of the ostinatos Barry uses derive from the Goldfinger theme, usually its first two chords, for instance just before Bond is knocked out by Oddjob, and when he comes to again. But the most extensive use of an ostinato based on the Goldfinger theme occurs in the cue “Dawn Raid on Fort Knox”, which uses a variation of the theme’s first two chords as the basis of most of the cue, heard from the start of this track:

Coming soon – On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Good discussion – I have never looked into the details of how a film score achieves its effect. You have set out very clearly some of the techniques used and how they work.

A question occurs to me, and it is no accident it is in relation to the ‘In Miami’ theme (curiosity about which set me on the path of search and inquiry that led me to discover your analysis).

I can well imagine you recall exactly the theme I have in mind. For others, it is the theme which kicks in immediately after the title song in the opening credit sequence. The scene starts with an airborne shot of an aeroplane trailer, ‘Welcome to Miami’, panning earthward for an aerial tracking shot of the glamourous Fontainbleau beach-front resort, gradually closing as the shot flies over.

This music – ‘In Miami’ – has held my imagination since the first time I saw Goldfinger, as a youngster. I’ve never forgotten it – and always wondered about it.

Picking up your theme of recurring motifs and repeated use of ostinato upon key melodic phrases, my question is: How the hell does this music fit in?

My own view – with no grasp of film score analysis, and even less grasp of musicianship – is that this brash and brassy theme (actually ragged and bluesy sax, if I recall, so not the usual Bond fare of steely sharp trumpet hits) needed to be sufficiently strong and distinct to follow immediately upon the epic title song. In addition, it needed quickly and strongly to establish a whole new setting, quite distinct from the pre-title sequence. The ‘risque’ blues and jazz accidentals which the tune turns upon, and which skirt so near to actual dissonance as to suggest a wild departure from the world of ordinary things, transport us at once. We are at the limit of the game – in terms of harmony – and in terms of wealth, morality, glamour, and goodness knows what. This music would not go amiss in a night scene, with the scope for deviance that the dark affords, but in fact it is used on a brilliant summer’s day. The lives of the wealthy and the reckless do not return to the humdrum with the rising of the sun. The party goes on…

Well, sorry, that is my long-winded and musically illiterate view. I really brought it up because it is the one piece of music which seems not to fit the scheme of devices and techniques you have so well outlined. Or do you also have an analysis of this short piece which places it snugly into the whole?

I enjoyed your comments and I hope I have not bored you with mine.

Cheers.

Oh, I listened to it on YouTube, and it is indeed sharp trumpets, and not so raggedy solo sax.

There is something rather seedy about the Miami music and its darkly dissonant harmonies, isn’t there? In terms of how it fits the score, of course there is no leitmotif here for Bond, Goldfinger, or Oddjob. But it does have Barry’s compositional stamp on it through the use of a two-chord ostinato. That swinging accompaniment that opens the cue persists throughout the first four phrases of the brass tune that comes in. Then it changes slightly on its second chord and reiterates that for the four phrases of the solo for also sax, so this could be considered a slight variation of the opening ostinato. The brass tune then returns and, along with it, the original ostinato for another four phrases then continues under the strings for two more phrases before halting on the final chord.

So in short, I’d say the cue blends with the rest of the score through its use of ostinato, but also its obvious jazz idiom, which is present in virtually all the other cues through the kinds of chords Barry writes, the syncopated rhythms, and of course the big band instrumentation. (Interestingly, Barry’s former drummer Bobby Richards is said to have arranged this particular cue on account of Barry being short for time. The music, however, is all Barry’s.)

Does anyone know the exact orchestration for the Goldfinger theme?

And how does John Barry achieve that amazing “way-wah” effect with the brass?

I’m orchestrating this piece for my youth group.

I believe it was one of the best movie themes ever written. It’s too bad that Mr. Barry didn’t get and academy award until he wrote “Born Free.”

Brilliant.

Hi David. I don’t know Barry’s exact orchestration for Goldfinger (I’d love to know myself!), but his wah-wah effect was originally written as a simple wah-wah mute for the trumpets, but then he decided to change it to the plunger mute. The rest of the story is as follows (as given in Burlingame):

“Once the plunger mute was decided on, Watkins [one of the trumpet players] said, Barry wanted the players to ‘make it even more dirty,’ so some of them added a throaty growl as they played the notes, ‘really kind of earthy. It just grew more and more, each time we played it. “Oh, yeah, that’s it! Give us more of that!”‘”

“Goldfinger” was the first LP I ever owned. Prior to seeing the movie I’d only collected 45’s of current hit songs. Changed my whole life as a collector of music and movie soundtracks in general. I have many of the Bond soundtracks and still believe “Goldfinger” was the all-time best and should have won the Academy Award for that year. That the inferior “Skyfall” theme song won and “Goldfinger” didn’t is too typical of the Hollywood crowd.

Hi,

I just downloaded a midi file of the song. I was surprised to hear G E F on “He’s the man”; in the song by Shirley Bassey, I have always heard G Eb F.

But the score here shows G E F :

https://www.sheetmusicdirect.com/fr-FR/se/ID_No/111888/Product.aspx

but that score seems corrected with a hand-written b :

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ateam/6341797948

On the piano it seems that most people plays a natural E as here :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Q4g_7yK1Go

For me the correct note is definitely Eb, is there an error in the score? It’s very strange, what do you think (or know)?

Kind regards.

Addendum

Eb here

https://www.musicnotes.com/sheetmusic/mtd.asp?ppn=MN0041485

But on the original score (pdf) natural E

https://www.johnbarry.org.uk/images/sheet/Goldfinger.pdf

Am I mistaken but isn’t the Tale of Tsar Saltan borrowed for this film?

hey the orig beginnings of the James Bond theme were taken from the beginning of. a. song by Adam faith called poor me also written by Barry

Fell down a rabbit hole today about Bond music, which included stumbling upon a video about the so-called “Bond Chord.” Being a fan of Bond movies and Wagner, I’ve tried figuring out (as a lay listener) if there’s a connection between that and the Tristan Chord. It might be akin to reading tea leaves, given that both are intended to sound in a way “unresolved,” but for what it’s worth, they both contain B and D sharp.

As for “Goldfinger” specifically, I also hear a bit of Wagner in the more “forboding” motifs that accompany Oddjob’s appearances and the Fort Knox sequence. The thumping timpani, “growling” brass, and general low rumble of the orchestra almost sound like they escaped from Siegfried’s funeral march from “Gotterdammerung.” More or less related, the “Skyfall” main theme has elements that sound a bit like Brunnhilde’s Immolation, which shares extramusical affinities with the final showdown at Bond’s family estate. But anyway…

Regarding the main theme itself, I’ve come to believe it sounds like Kurt Weill and Richard Strauss collaborated on the Liebestod from “Tristan und Isolde.” (Apologies to fans of both.) It’s the jaunty “jazz” of Mackie Messer with “murder ballad” lyrics (which Barry himself mentioned as inspiration), but accompanied by the kind of dense Romantic orchestration (albeit scaled down for “Goldfinger”) that was Strauss’ metier. A glib perception, I suppose, but sex and death have frequently been in close proximity to Bond’s world.