Ennio Morricone has one of the most distinctive sounds in all of film music, a highly unusual trait in a business where the composer is generally a musical chameleon, writing in different styles to suit different films. But in his film themes, Morricone tends to draw upon a relatively limited palette for melody and harmony, hence giving his music a very recognizable sound. And yet, it is not as if all of his scores sound the same. What tends to separate one from the next is his unique orchestrations. Indeed, in a translated volume of lectures by Morricone and musicologist Sergio Miceli, Morricone remarks that

“I have always believed that the inventive use of tone color is one of a film composer’s most important means of expression.”

And in discussing the main title cues for the “dollars” films, he notes that he prioritizes tone color even above melody:

“Melody is not so important. … If you take away the melody from all my pieces of this or other types, the piece still will remain … on its own feet. But the theme helps the director and serves the public. Perhaps I am deceiving myself by thinking that while following the theme, people also assimilate and appreciate the instrumental solutions.”

While Morricone’s colorful orchestrations are obvious in his scores, his frequent melodic and harmonic devices are less so. This and the following two posts will provide film music analyses that examine these devices in his themes for Once Upon a Time in the West, another Leone western that followed soon after the “dollars” trilogy. I begin with Jill’s theme, or what is generally referred to as the film’s main theme. Below is a recording of the complete cue:

The Introduction

Jill’s theme falls into two sections according to the melodic material: an introduction and a main theme, the latter divided into a scheme of ABAA. The introduction comprises a two-phrase melody stated twice. Morricone immediately reveals his penchant for unusual scorings as he sets the first statement for harpsichord and vibraphone accompanied by the cello. The melody here is constructed almost entirely out of one of Morricone’s favorite melodic devices: the anticipation, which states a note twice successively, first on a weak beat then on a strong beat:

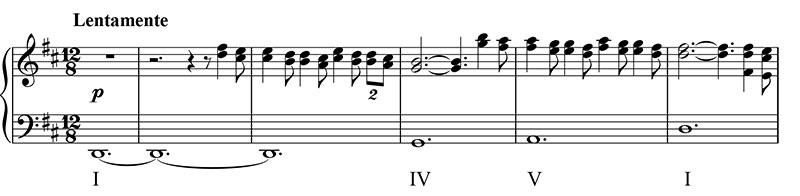

Harmonically, the introduction is based on a very simple progression, I-IV-V-I, or what might be called the primary progression since it is one of the most basic progressions in all of music (see example below). Its simplicity may perhaps evoke Jill’s desire to live a simple life out west with her husband Brett McBain after having moved from New Orleans.

The second statement of the introduction is considerably warmer in tone as the middle registers become filled out, the rich sound of the alto flute being added to the melody and the string section to the accompaniment.

The Main Theme

First Statement of A

Once again, Morricone’s unique sense of scoring comes to the fore in the A section with a broad new melody sung by a wordless soprano (Edda Dell’Orso, who sang for several other Morricone scores, perhaps most notably for “The Ecstasy of Gold” in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly). As an entirely human instrument, the voice lends the music a poignant quality that fits well with the tragic circumstances that Jill finds herself in. And its wordlessness in this case makes its impact even more direct as it is treated as a purely musical sound rather than a vehicle for a text.

While the melody of this section may seem fairly traditional, it nevertheless bears “Morriconean” trademarks. As the composer himself has said,

“Certainly the theme [in general] is extremely important, even if I personally have always considered it of little significance. For this reason, especially in the first films of Leone but also … on many occasions afterward, I have attempted to distinguish it, to subtract it from its conventional function. In some cases I have augmented the result with timbre, in others with the pursuit of a theme made of intervals.”

“A theme made of intervals” describes many of Morricone’s themes. In the case of Jill’s theme, the interval of the sixth is especially prominent as it begins the A theme and is stated four times within its eight bars:

This interval has a long association with love and feminine beauty in classical music, the opening of Liszt’s Liebestraum being a prime example:

Liszt Liebestraum

In the context of Once Upon a Time in the West, the association is especially apt and adds to the poignancy of the theme by suggesting the love Jill feels for her dead husband.

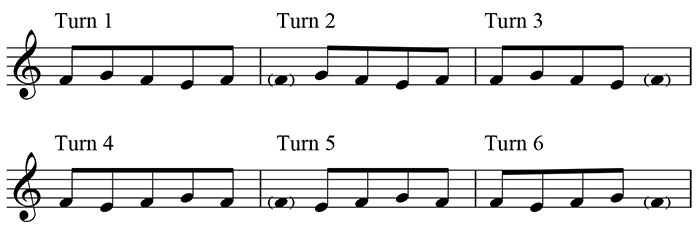

Another Morriconean trait of this section is its reliance on a melodic figure known as the turn, which involves beginning on a note, rising a step and returning, then falling a step and returning. In addition, this figure may appear in inverted form or may omit its first or last note. It may therefore take the following six forms:

This figure appears in a vast number of Morricone themes, for example at the very opening of “Gabriel’s Oboe” from The Mission (starting from 0:16):

The speed of the figure may vary but its appearance is always unmistakable. In Jill’s theme, a turn enters immediately after the opening sixth and at two other locations in its brief eight-bar length:

The melodic figures discussed so far—the anticipation and the turn—both appear in many other of Morricone’s themes and with entirely different emotional expressions. Thus, it seems that these figures are not wedded to a particular dramatic situation and are simply a part of Morricone’s style.

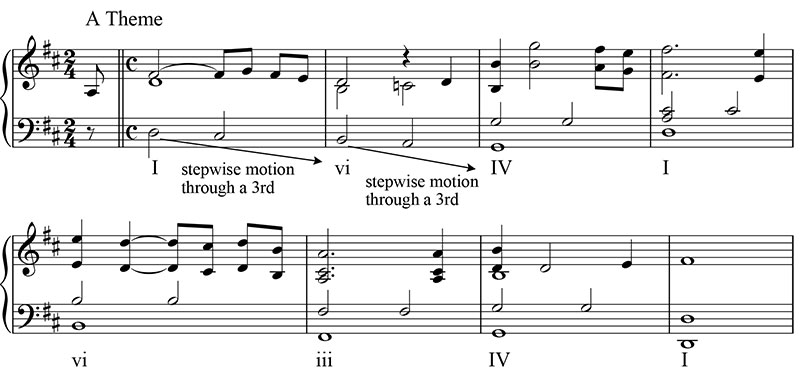

Harmonically, the first half of this section’s theme sounds a progression that moves through four chords, I-vi-IV-I, with intervening chords between the first two pairs. This progression is essentially a form of I-IV-I, or what is called a “plagal” progression, but with the insertion of the vi chord, which creates a line of descending thirds in the bass. For this reason, I call it the plagal thirds progression, and it is one that appears in a great many of Morricone’s themes. Typically, this progression fills in one or both of those thirds with stepwise motion to create an even smoother stepwise line in the bass, as there is here:

Perhaps through its stepwise bassline, its simple pattern of chords in descending thirds, and its alternation of major and minor chords, the progression has a profundity that suggests the expression of one’s deepest and most intimate emotions. Hence Morricone tends to employ it in scenes that expose a character’s tender side, as in “Ness and His Family” from The Untouchables and the flashback scenes (main theme) from Duck, You Sucker! (A Fistful of Dynamite).

The Untouchables

Duck, You Sucker! (A Fistful of Dynamite) (from 1:29)

As seen in the previous score example, the second half of this section’s theme reiterates the plagal thirds progression in a slightly varied form, vi-iii-IV-I, in which the initial I chord is omitted and a iii chord is inserted between the vi and IV, as in (I)-vi-(iii)-IV-I. Thus, the deeply emotional quality of the harmony is allowed to continue throughout the eight bars of this section’s theme.

B Section (Bridge)

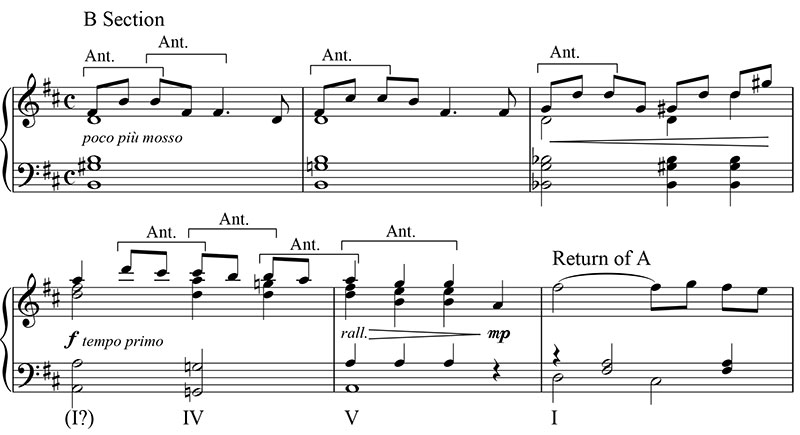

Structurally, this brief five-bar passage serves as a contrast to the A theme in order that it may sound fresh again upon its return immediately afterward. Notably, the melody and harmony draw on what has already occurred, though in varied form. All five bars make use of the anticipation figure in the melody, and the last two bars suggest the primary progression of I-IV-V-I (the last I chord begins the return of the A theme):

Even in its short span, this bridge section rises to a stirring climax to Jill’s theme that, in the film, corresponds to the crane shot that reveals the bustling town in which Jill has arrived. Musically, the climax is suitably placed as it provides an emotional high point before quickly dwindling and allowing us to take a metaphorical “breath” before returning to the A theme.

Second Statement of A

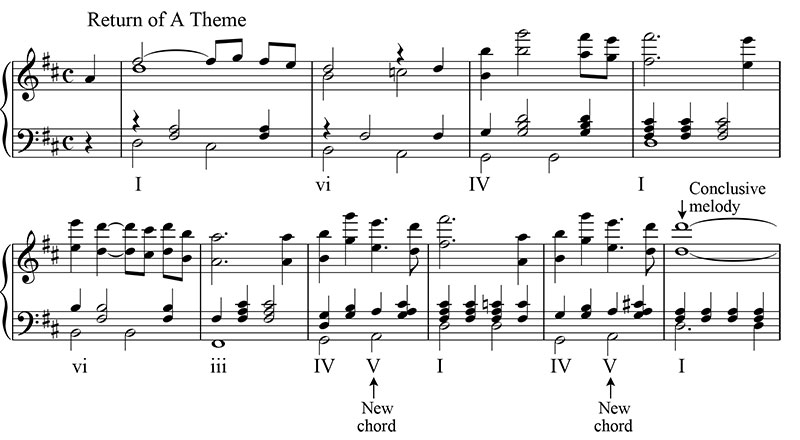

Naturally, the scoring of the A theme is altered upon its return, now with the melody in the strings, in a higher register, and accompanied by wordless choir for a grander effect. In terms of harmony, the theme is the same as before but with one important change: the final two bars of the eight-bar theme now add the V (dominant) chord at the cadence, providing a satisfying sense of resolution and closure that was not there before:

The final IV-V-I is then reiterated with a more conclusive end to the melody. Notice that this progression is in fact the primary progression we heard in the introduction and bridge sections (though with the initial chord omitted). Thus, Morricone is once again drawing on previous material and retaining an economical palette of melodic and harmonic devices in the cue.

Third Statement of A

As in many popular songs, the final (in this case, third) statement of the theme is transposed up a semitone, lending it a greater energy than before, a quality that Morricone emphasizes through its scoring with a lusher orchestration that includes both the strings and wordless soprano in addition to the choir and orchestra. Immediately after this statement, Morricone adds a two-bar tag with the chords IV-I, a simplified form of the plagal thirds progression that brings the entire cue to a convincing close.

Conclusion

To summarize, unlike most film composers, Ennio Morricone tends to draw upon a relatively small set of melodic and harmonic devices that recur throughout his film music. These devices give his music a very consistent sound that renders it highly recognizable even though the orchestration can vary drastically from film to film, or even cue to cue. In Jill’s theme, the main melodic devices were the anticipation and turn figures, and the main harmonic devices the primary progression (I-IV-V-I) and the plagal thirds progression (I-vi-IV-I). Perhaps it is Morricone’s generally narrow set of melodic figures that leads him to dismiss melody as unimportant to his conception of film scoring. In other words, because his melodies draw from a relatively small group of figures, he may feel that one figure is as good as another. Given the beauty and seeming perfection of the melody of Jill’s theme, however, it is difficult to imagine other figures working just as well.

Coming soon… Morricone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (Part 2 of 3): Cheyenne’s Theme

Dear Mark,

Thank you for yet another of your wonderful film music analyses. I have been following your site in the past months, and found so many interesting things about my favourite composers (Williams, Morricone) that are not available anywhere.

You really should consider writing a history of film music, providing similar analysis of the best film scores, supporting it with sheet music excerpts (this is what other film music history books lack and what makes your site so unique).

Another of my favourites from Morricone is his music for “A few dollars more”, the second part of the dollar trilogy. I hope you can devote some time to that film as well in the future.

Has the Morricone book you mention sheet music excerpts?

Or do you take your sheet music examples from some published anthology, or do you simply transcribe what you hear?

All the best, keep up your wonderful blog,

Karoly

Thank you, Karoly. Writing a book on film music is something I would very much like to do. It’s probably just a matter of time.

For a Few Dollars More is a favourite of mine as well. I’ll put it on my “to do” list of recommendations I keep from readers.

As for the musical excerpts, there is a great three-volume set of Morricone’s film music arranged for piano called The Best of Ennio Morricone, of which the first volume has the Once Upon a Time in the West themes. Unlike many anthologies, they’re very well done in that they avoid the “easy piano” temptation and go for a more intermediate level, leaving in just the right notes to make it sound like the film score. That said, I do take liberties with it if I feel I want it to be even closer to the original score or just want to emphasize different things. Sometimes, though, I don’t have a score, so I just use my ears to write what I hear, as in my recent Man of Steel post.

Thanks again for your kind response.

Dear Mark,

I am looking forward to your planned book about film music.

As for Morricone, most of his westerns have some kind of piano transcriptions. But there is a comedy western, Occhio alla Penna (Buddy Goes West) (1981, ITA), whose music is my favourite of his scores, and yet I did not see any published piano version from this movie.

I highly recommend that you listen to it. I would be interested in an analysis of this music as well.

All the best,

Karoly

Thanks, Karoly. I’ve put this other score on my to-do list as well. I didn’t find it in my Morricone piano collections either. Maybe in a future volume (let’s hope).

Much appreciated thoughts.

I am pleasantly surprised by their insightful comments and analysis of the beautiful piece of Morricone. Please accept my congratulations from a Chilean musician.

Thanks very much, Hernán!

Can you tell me what type of oboe is used for the opening of Ecstasy of Gold?

@Julian: That’s an English horn. Its range is a fifth lower than the oboe and it has a warm, rich sound, perfect for lyrical melodies with long notes like this opening.

Such a great analysis! I’m reading the three chapters since 2 days and love all the insight on Ennio’s music. You really helped putting some light on his method of composition. I’m waiting for the For a Few Dollars More analysis, I hope it’s still on your to do list ! Regards.

Thanks, Frank! I hope to do some more on Morricone in the future. Something I’ve always wanted to write about is the opening of Once Upon a Time in the West, which is done with sounds that Morricone “composed” rather than music.

You mean, the 15 min opening sequence with the 3 men waiting for Harmonica? I didn’t know it was “composed” by Morricone! So, he did the sound designer job before it was ever invented! All the McBain family sequence after also seems very “sound designed”.

I’ve been doing some Morricone music interpretation myself with a project called “Orgasmo Sonore – Revisiting Obscure Film Music”, but more with a modern rock approach. You can have a look here (3rd song is La Resa Dei Conti by Morricone)

https://soundcloud.com/orgasmo-sonore

Best,

Frank

Hi Mark, As an orchestral conductor I am frustrated as to how difficult it is to obtain the written music and orchestral scores. I desperately want to play the “Once upon a time in the west” music with my orchestra. Is there any way I can get an orchestral arrangement with score or just the score so I can fulfil my ambition to conduct this work. Can you help me please ? Would I be able to orchestrate from the Piano Book 1 which you mention (the best of morricone) as a last resort.

Hi Norman,

Alas, orchestral scores of Morricone’s music have not been made commercially available, as far as I know. But at least the piano arrangements in the books I mention are quite good arrangements, and I could see them being arranged successfully with a good ear. It’s hard to know exactly what combination of sounds one is hearing with Morricone, though, because his orchestrations so often include unusual instruments to blend with orchestral ones. Like with Jill’s theme, it sounds like there’s a harpsichord with vibraphone and cello amongst other things. And does Cheyenne’s theme use coconut shells rather than temple blocks? I wouldn’t put it past him, but it’s hard to know. Sorry I can’t be of more help – I share your frustration. Hopefully one day we will start to see commercial releases of some of his scores.

Thank you Mark at least I now know the position I will try and get the piano book and make my own orchestration.

Hello

I would like to get information about your book on film music. I am from Greece. Please send me the price for a pdf version. Thank you.

Andreas