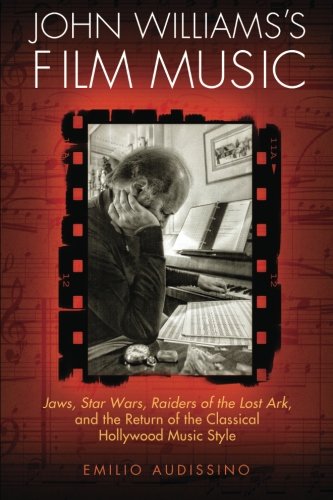

With all the success John Williams has enjoyed thus far over his extensive career, one might believe there to be a wealth of writings on the composer. The truth, however, is that John Williams’s Film Music, published just this year, is the first English-language book to be published on John Williams and a much needed contribution to the nearly non-existent body of work on Williams.

Written by Emilio Audissino, a filmmaker, screen writer, and film scholar, the book stems from the author’s PhD dissertation but has been translated from Italian, abbreviated, and “de-academized” (as Audissino puts it) for the sake of reaching a wider audience. On the whole, it is a thorough, convincing, and enjoyable treatment of how Williams’ has managed to recapture much of the spirit of good old music from Hollywood’s Golden Age of the 1930s and 40s (or what is commonly referred to as “classical Hollywood”) in the manner of Erich Korngold, Max Steiner, Miklós Rózsa, and company.

Audissino sets out by taking the reader through a survey of Hollywood film music history beginning with the silents and reaching Williams’ classical revival with the major films of the 1970s. For those who have read something on this before, it will be quite familiar but even so, there are new tidbits to be found and it is always enriching to have the story told through the lens of another scholar, since the interpretation of events is never quite the same. Thus, one may be surprised to read on p. 59 that in the “modern” film music style of the 1960s,

If we examine the works of Ennio Morricone (1928-), John Barry (1933-2011), and Henry Mancini (1924-94), three of the most successful representatives of this new style, it is patent that the classical-style “spatial perceptive function” (the case in which music directs the viewer’s attention to a particular element inside the framing) holds a minority position in the new style. Consequently, the Mickey-Mousing and leitmotiv techniques became obsolete.

Of course, Morricone, Barry, and Mancini all wrote “themes” for various characters in the films they scored, whether it was Jill from Once Upon a Time in the West, James Bond, or The Phantom from The Pink Panther. But Audissino’s point is that these themes tended to be closed musical numbers and so did not seek to catch moment-to-moment emotional changes but rather express an emotion that described longer stretches, even an entire scene. And this idea aptly describes a key difference between, say, a Morricone theme and a Korngold leitmotif.

Another great quality of this book is that Audissino manages to find the perfect Williams quote for just about every situation. One of my favourites is that of Williams discussing his approach to the main title of Star Wars (pp. 74-75):

The opening of the film was visually so stunning, with that lettering that comes out and the spaceships and so on, that it was clear that that music had to kind of smack you right in the eye and do something very strong. It’s in my mind a very simple, very direct tune that jumps an octave in a very dramatic way, and has a triplet placed in it that has a kind of grab. I tried to construct something that again would have this idealistic, uplifting but military flare to it. And set it in brass instruments, which I love anyway, which I used to play as a student, as a youngster. And try to get it so it’s set in the most brilliant register of the trumpets, horns and trombones so that we’d have a blazingly brilliant fanfare at the opening of the piece. And contrast that with the second theme that was lyrical and romantic and adventurous also. And give it all a kind of ceremonial… it’s not a march but very nearly that. So you almost kind of want to [Williams laughs] [pat] your feet to it or stand up and salute when you hear it—I mean there’s a little bit of that ceremonial aspect. More than a little I think.

And Audissino puts the quote in appropriate context by pointing up the many classical Hollywood traits that pervade this main title music. The one thing I would question with regard to Audissino’s discussion of Star Wars is his claim that George Lucas “planned to have the music track made of preexisting symphonic selections, or at least to use preexisting themes arranged as leitmotifs for the film” (p. 71), then cites the conversation Lucas had with Williams in which the latter supposed convinced him otherwise.

Myself, I am of the opinion that there has been some kind of mix-up in the communication of this little anecdote. As great as it sounds that Williams was the one who thought Star Wars should have an original score, it just doesn’t ring true—why hire one of the hottest composers in Hollywood (who has just won an Oscar with Jaws) if all that’s going to be done is arranging old music? My thinking is that Lucas wanted Williams to conjure up something like Holst here or like Stravinsky there, and that this was Lucas’ idea for the entire film. And probably the clear references to these composers in the film are the remnants of what might have been for the entire film had Williams not spoken up.

For me, the most eye-opening chapter was the one on Williams’ early years. There, after giving a synopsis of Williams’ career highlights during the 1960s and early 1970s, Audissino traces the beginnings of Williams’ classical Hollywood revival in several lesser known scores like How to Steal a Million, Fitzwilly, and Not with My Wife, You Don’t!, and compares them to scores in the “modern” style by one of the most prominent composers of the time, Henry Mancini. It is fascinating to read this because Williams’ early scores generally go unmentioned in any written discussion of his work. But Audissino convincingly argues that their leitmotivic, symphonic, and Mickey Mousing qualities are more prominent than in Mancini (and by extension other “modern” style composers of the era).

In the latter portion of the book, Williams’ score for Raiders of the Lost Ark gets a thorough scene-by-scene analysis of how the music functions. If there are any doubts left at this point that Williams drew on classical Hollywood techniques, this chapter puts them to rest. And evidence of Spielberg’s own fondness for the classical style of filmmaking is discussed as well to further strengthen the argument.

Another enlightening aspect of the book is its demonstration of Williams’ commitment to performing original versions of classical Hollywood film score cues and programming a good deal of them in public concerts, particularly those televised with the Boston Pops Orchestra. In this way, it becomes clear that Williams has been an ardent promoter of film music outside of Hollywood, which has helped to legitimize it as a form of music worthy of concert performance, recordings, and scholarly study. By the end of the book, especially after the chapter on Williams’ tenure with the Pops, one is astounded by just how much the man has contributed in this vein.

Finally, one handy feature of the book is its two appendices, one giving short synopses of the films Williams has scored for Spielberg and Lucas (okay, we can look this up on Wikipedia, but let’s face it, it’s a distraction when you’re reading the book), and the other is a comprehensive list of Williams’ total output. There is also a short glossary containing some key musical and filmmaking terms that many will undoubtedly find convenient.

So whether you’re at all interested in film scores—their history, their changing styles, their reception over the years—or in the music of John Williams in particular, you will find much to enjoy in this new book. It’s the kind of thing we need a lot more of, so I’m very glad Audissino has given us a great starting point.

Hi Mark,

Thanks fo calling my attention to this book.

However, based on the preview on Amazon, there are very few sheet music examples in the book, and they probably do not go into detail concerning the accompanying harmonies of the various motives.

Perhaps the only novelty is the identification of the “Wrath of God” motif in Raiders of the Lost Arc. Is its harmonization discussed, or is it only the melody transcribed?

That is why I like your site, you are probably the only one who provides such a detailed analysis of a current film music motif, describing the melody, rhytm and harmonization.

I would be glad to read such a book on John Williams, but the scope of the above mentioned book lies probably elsewhere.

Hello again, Karoly. You’re right that there aren’t many musical examples and discussion of harmony is minimal, but that’s because Audissino never claims this to be a musicological book. As he states in the introduction (p. 7),

“There are many film composers who can be studied and appreciated for their fine musical achievements, and perhaps such studies can be undertaken more efficiently by musicologists.”

Audissino is a film historian with musical training, though not a musicologist. So his points are argued from a historical perspective rather than a music-theoretical one. The scarcity of musical analyses of film music is one of the main reasons I started this blog and hope that others like yourself enjoy about it. Cheers.

It was more technical than I expected, but overall enjoyable. I need to watch more movies with his music to fully appreciate them now!