The “Force theme”, also known as “Ben Kenobi’s theme”, “Obi-Wan’s theme”, or “May the Force Be With You”, is one of the most beloved of John Williams’ music for the Star Wars saga. It appears in all six films, but perhaps most memorably in the very first, Episode IV: A New Hope, in the cue “Binary Sunset”, where Luke Skywalker contemplates his future while watching a pair of suns set on the horizon:

Hear it in this clip from 2:21:

Hear it in this clip from 2:21:

Emotionally, the theme ranges from the gentle poignancy of cues like this that can bring a tear to one’s eye to a brash militarism that can rouse the spirits and make us root for the good guys. So what is it that gives this theme its emotional qualities and makes it such a perfect fit for what we see onscreen? My film music analysis below gives some ideas.

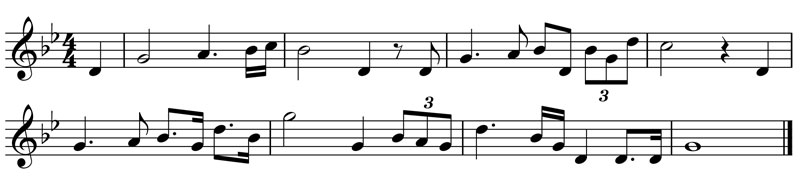

Melody

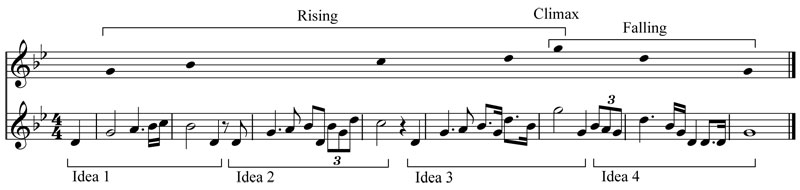

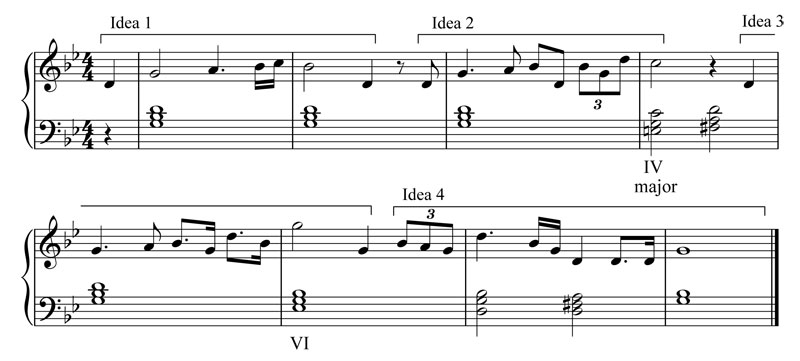

Let’s start with the theme’s melody, which divides into four two-bar ideas. In the example below, notice that the goal notes of each idea together form a shape that rises through the first three ideas, reaches a climax, then falls with the last:

Thus, the theme gradually builds to a climax over a long stretch, then more quickly relaxes and comes to an end. Because this is the general pattern of tension found in most action narratives and the struggles they involve, you might call this the “struggle” contour.

Thus, the theme gradually builds to a climax over a long stretch, then more quickly relaxes and comes to an end. Because this is the general pattern of tension found in most action narratives and the struggles they involve, you might call this the “struggle” contour.

But the Force theme goes even further than this in its sense of struggle. In the example below, I show the prominent scale steps the melody moves through, as shown by the numbers with caret marks over them.

After a brief pickup note, the first idea starts with a slow rise from the first note of the scale (tonic), up to the second, then quickly through the third and fourth before sinking back down to the third again. In this quick rise to the fourth note, it’s as though the theme wants to continue its upward motion but is thwarted from doing so.

After a brief pickup note, the first idea starts with a slow rise from the first note of the scale (tonic), up to the second, then quickly through the third and fourth before sinking back down to the third again. In this quick rise to the fourth note, it’s as though the theme wants to continue its upward motion but is thwarted from doing so.

In the second idea, we get the same rise up the first, second, and third scale notes, and quickly touch on the fifth before falling back to the fourth. Again, the theme seems to want to rise higher to the fifth and beyond, but somehow it just cannot—it’s struggling hard to make its way up the scale.

Finally, in the third idea, we rise from the first, through second, third, and fifth up to an octave (eight) above the first note. Reaching this high note through this kind of slow rise gives it the feeling of a climax, a success of sorts. And in the “Binary Sunset” cue above, Williams emphasizes this climax with a fuller scoring for the orchestra and with the melody in the strings, both of which add to the poignancy of the effect.

Just as we reach this climax, the melody quickly begins to fall again, eventually ending on the tonic we started on. Thus in its first three ideas, the melody suggests a “striving” quality, a long, arduous road towards a success that is tarnished with setbacks both large and small. Surely this is one of the reasons why the theme feels “right” as a musical symbol of not just Obi-Wan’s struggle, but the Rebels’ struggle more generally.

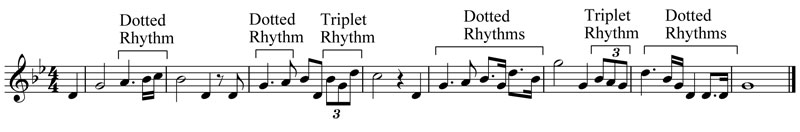

Rhythm

The rhythm of the Force theme is one of its most distinctive features. But notice some of the specifics of its rhythm: it’s set in a four-beat meter, beats 1 and 3 of each bar are almost always emphasized with a note that is a beat or two long, and there are conspicuous dotted (long-short) rhythms and triplet rhythms:

These are all characteristics of a march, so even in its gentle versions, the theme has an underlying military quality. No doubt, this is why it is well suited to represent the Jedis and Rebellion, and also why it is entirely fitting when the theme assumes a more obvious march-like character with a faster tempo and brassier orchestration.

These are all characteristics of a march, so even in its gentle versions, the theme has an underlying military quality. No doubt, this is why it is well suited to represent the Jedis and Rebellion, and also why it is entirely fitting when the theme assumes a more obvious march-like character with a faster tempo and brassier orchestration.

Harmony

The Force theme is set in a minor key, and minor keys usually signal some kind of negative emotion. But it’s not all doom and gloom in this theme. The chord ending the second idea is a more positive major IV chord:

Normally, IV is a minor chord in a minor key, so this change to major gives us a sense of hope within a prevailing negative context, which is precisely the situation of the Rebels in relation to the powerful Empire.

Normally, IV is a minor chord in a minor key, so this change to major gives us a sense of hope within a prevailing negative context, which is precisely the situation of the Rebels in relation to the powerful Empire.

At the end of the theme’s third idea, the climax emerges over another major chord, VI (see above example). Because this chord is found naturally within the minor scale, we have not lost the sense of the negative context. But the sound of the major chord on VI strikes an overwhelmingly positive tone, especially when combined with a loud melodic climax, as in “Binary Sunset”, so tends to sound like a heroic triumph of sorts. This is likely why the chord is frequently heard in the themes of superheroes, Elfman’s and Zimmer’s themes for Batman being other examples.

The final chord (or “cadence”) of most of Williams’ themes gives a sense of punctuation, a sign that we have finished with the theme altogether, or at least with that section of it. The Force theme is no exception, since in its fullest form, as heard in “The Throne Room” march, its ends with a final-sounding tonic chord. In “Binary Sunset”, the theme leads us to expect this same closure on a tonic chord, but trails off before reaching it. Listen again to “Binary Sunset”, starting from 2:36:

Besides the “Throne Room”, the only time the theme does reach a final chord in A New Hope, it is tainted by dissonance, as in the second statement in the cue above—hear its last idea from 3:51 to the end. In every other instance of the Force theme in this film, we only hear its first half. And as we have seen, when the second half is sounded, it either does not resolve or moves to a dissonant chord that sounds equally unresolved. The theme is only completed in the Throne Room march, after the Rebels’ mission to destroy the Death Star has been completed. Thus, the success of the mission is mirrored in the resolution of the music. Hear this final version of the theme below from 0:17:

Orchestration

The two main versions of the Force theme heard in A New Hope are differentiated largely by their orchestration. The gentle statements set the theme’s melody softly in lyrical instruments like the horn, strings, or winds. And they are often accompanied by fast, repeated notes (or a “tremolo”) high up in the strings, which has a shimmering effect that gives the theme a contemplative or vulnerable sound.

In its more aggressive, militaristic settings, the melody assumes a loud and strident tone in the trumpets and/or trombones, and there is usually a heavy accompaniment in the rest of the orchestra that suggests the emotional weight of the situation at hand. The intensity of these statements of the theme are usually bolstered by the use of dissonant harmony, as below in the cue “The Battle of Yavin”, starting at 3:40:

The appearance of these two main types of orchestration correspond with the general shape of the film’s narrative: in the earlier part of the film, it is not certain whether Luke will become the hero the Rebellion so desperately needs—hence the more contemplative forms of the Force theme. But as Luke learns the ways of the Force with Obi-Wan and begins to act more and more like a hero, we hear more of the brassy military form of the theme, especially in the final battle with the Death Star.

Conclusion

The Force theme packs a lot of meaning into a very small space. Its melody has the contour of a “struggle” and strives to reach a hard-won climax. Its underlying march rhythm gives it an appropriately military air, even when it is scored in its gentler versions. Its major chords on IV and VI lend it a feeling of hope and heroism within the larger negative climate of the minor scale. Its lack of resolution to a clean final chord in all but the last statement in “The Throne Room” gives it the sense of struggling towards a goal that is only achieved at the very end of the film. And its differences in orchestration correspond with Obi-Wan’s shaping of Luke into the hero of the story. For all these reasons, the Force theme is a natural fit with Luke, the Force, and more generally, the Rebellion.

No wonder the theme is considered one of the best of the Star Wars films.

Coming soon – Part 2: Star Wars, main title

very nicely done mark.

e

Clear & detailed writing on your part, Mr. Richards.

Nonetheless, the subject matter and related musical material is too plebian for my personal tastes.

Heroism? Martial march rhythms? Why a pop culture franchise receives such affection escapes me.

I find the whole STAR WARS mythology to be rather juvenile and its large popularity puzzling. Whenever I hear the main themes from STAR WARS or SUPERMAN or RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, I groan “Oh – not THAT … please not again!”.

The sheer over-exposure of these types of heroic marches yields numbness and apathy in me. Yet there are people who LOVE this music, never tire of it, and a few folks even get PhDs in it.

Anyways, as an individual who owns hundreds of soundtracks and 20th century classical music albums, I’d much more interested in reading analysis on non-mainstream/non-Hollywood film music.

There’s SO much out there (whether it be Alex North’s PONY SOLDIER or Piero Piccioni’s IL BELL’ANTONIO or Charles Koechlin’s “Seven Stars Symphony” or Giacinto Scelsi’s “Aion”, etc.), why limit oneself to John Williams blockbusters or the James Bond franchise or Bernard Herrmann warhorses?

Please don’t take this the wrong way; I’m not criticizing your hard work and labor of love. I wish to open the door into discussions about much more idiosyncratic (and therefore more fascinating) music compositions.

STAR WARS & PSYCHO get enough pop-culture analysis (that’s why there’s lots of interviews and documentaries within DVD extras!).

Do something much more unique – such as analyze the music heard in an Ingmar Bergman film or illustrate the parallels between Karol Szymanowski’s opera “King Roger” and Loek Dikker’s film score for THE 4TH MAN. Believe me – this stuff is really out there! Who needs James Bond or CITIZEN KANE? They’ve been done to death. 🙂

We cannot blame “The Force Theme” for being part of a blockbuster film. This tidy musical statement is strong and versatile. “A New Hope” as a story is an exercise in literary archetype; “The Force Theme” as a standalone piece has archetypal power, particularly in its gentler expressions, where it represents sacrifice and struggle but no guarantees. How wonderful! Try playing it on your piano or instrument of choice and you will recognize this kernel of genius.

You are on FILMMUSICNOTES.com. Did you expect something other than notes on the music of blockbuster films? lol

You sir are completely wrong.. I never comment but your calling this analysis plebeian shows your complete lack of music understanding in general. I came looking for an analysis to compare to my own because I recreated the song from ear and wanted to verify some of the finer points such as the major IV chord and the major six which are so elegantly added to the song so creative so perfect and unusual for typical pop music and yet so widely and universally loved I just had to understand why. I agree I wish the author took this idea and explanation even further but plebeian I think now and the non appreciation for original Star Wars and john Williams and taking the time to come here and tell us that?? Go back to your cave troll grinch.

What a shmuck

@Ronald: As popular as these Williams themes are, the truth is that there simply aren’t the kind of musicological analyses on them that you are claiming there are. At present, there is no musicological book on the Star Wars music or on John Williams’ music in general. So I’m adding what I can informally by writing about them here. We all have our own tastes, so I can understand if this music isn’t for you, but why criticize those who do have respect for it?

Hi, MR. No disrespect intended. The music of STAR WARS is not bad music, and it’s worthy of academic acknowledgment and formal treatment.

It’s just that when a person has watched more than 600 films and has an album collection spanning music written by greater than 400 different composers, one should realize that John Williams is not the be-all & end-all of film music. Actually, no one composer should dominate. Popularity should not be a barometer to gauge quality, etc.

My main bugaboo is really not aimed at you or your website – good luck with your endeavors.

Rather, I’m disenchanted with Hollywood’s fixations on summer blockbusters over the past 35 years and their continual aim to capture the high school/college-age audience demographics.

Twenty-somethings in the 21st century have grown up so accustomed with CGI effects that few are equipped to appreciate the cinematic adaptations of – say – plays by Tennessee Williams or Harold Pinter. I think this is a sad thing. Perhaps you may not.

Speaking for myself, if I ever attain the age of 80 (I’m 45 now) then I won’t be thinking about things such as STAR WARS in my old age. I will probably still be advocating the cinema of Antonioni and music by Arne Nordheim, but my days of playing the music of STAR WARS have already elapsed.

You’re welcome to the Spielberg/Williams collaborations – just leave the Claude Chabrol films for me! 🙂

Re: Ronald. I get where you’re coming from about about the shift from high culture to pop culture, but why not do something about it yourself? Set up your own blog and invest your time in studying say the Alex North collection at UCLA or tracking down the locations of other manuscripts from more obscure foreign composers. I’d love to read an analysis on North’s The Shoes of the Fisherman, Pierre Jansen’s Le Boucher, Sven Nykvist’s Persona, or the late Richard Rodney Bennett’s Figures in a Landscape.

The reason why Mark is studying these Williams scores and not more obscure works is because the manuscripts (sketches or full scores) for these are in circulation online, along with the fact that he’d be writing for a narrower, less universal audience. But most importantly it’s a matter of availability.

For good or bad, these Williams scores are ingrained our pop consciousness. Understanding why these are so effective, and why they work dramatically is something few academics have bothered to ask.

Ronald Z: the only thing that’s juvenile here is your own desire to flaunt your cultural capital and reinforce it by some obsolete hierarchical cultural standards by positioning yourself against “the popular”. This isn’t any kind of deep or learned artistic appreciation, it’s a way for you to feed your superiority complex. And at 45 years old? Tip: quit the namedropping.

Dear Mr. Ronald Z,

I would like to reply with some points on your comment:

1) As Mr. Richards said, a musicological analysis on John Williams is scarce (although many people believe that the opposite applies).

2) The fact that the Star Wars films (or Indiana Jones, or E.T or similar films) are very popular doesn’t diminish the quality of music. Yes, many people know only the themes and make their criticism based upon that, but if you listen to the Star Wars music as a whole, with the various statements of the themes, their development, their metamorphoses across the span of the film (be it in melody, harmony, rhythm and orchestration), the motivic connection between them etc., you will find that there is a strong structure with internal unity that is difficult to achieve and by no means it’s plebian.

3) I was wondering if you are a composer yourself. Well, anyhow, a melody like this which seems simple and inevitable, is very difficult for a composer, at least in my opinion, much more difficult to conceive than a cluster and “sound effects” music by a contemporary composer. Composers can spend days or weeks on such melodies which I repeat sound simple, but are not simplistic at all. I can compare the gift of melody in Mr. Williams with that of Tchaikovsky’s, which I’m sure you know – although popular- isn’t considered a bad composer.

4) If you are into avant garde music from what I have gathered, I suggest you listen to other scores of John Williams like Images and Close Encounters. I’m sure you can find there something that will be more in your field.

Well said. I think many Neoclassicists felt the same way in their reaction against the extremes of 20th-century music in their return to the strongly communicative and relatable musical techniques of the early Romanticists and prior. I also admire Williams’ commitment to composing melodies that seem inevitable, which invariably entails harnessing some of the clichés look down upon by the avant-garde.

Very well done Mr. Richards! It is such a pity John Williams never published such an important version of the Force Theme leitmotif in his Concert suites. The closest John Williams gets is in his edited version of Throne Room & End Title with the oboe. This version however is built up using sevenths and sixths and doesn’t resolve as nicely.

Thanks, Reilly. Yes, I agree it’s too bad we don’t have a published version of the Force Theme. Certainly that has much to do with it’s short length. And something about it’s emotional quality prevents it from being included in the end credit music, which are essentially little symphonies that sum up the primary themes of the film. The Rebel Fanfare makes it in, for example, but it works very well in conjunction with Luke’s Theme (the Star Wars main theme). I’m not sure the Force Theme could do this as well.

Really appreciate your time on these articles. They’re a great read! Thank you so much 🙂

Hi Mark

quick question . Is the use of the Maj. IV an indication that this is Dorian ? or is this just a one off? as the following chord is the Maj. V ( classical minor harmony ) is THAT proof that this isn’t Dorian ?

confused of north london

Great question, Ed. The possibility of a Dorian mode for the major IV is probably excluded by the use of the VI chord in the 2nd phrase, which uses the minor scale’s regular sixth degree rather than the raised one we would hear with Dorian. My guess is that the major IV is the result of the melodic minor scale. That is, the IV goes to V to start the next phrase, so the raised 6 in IV (E-natural) leads to the raised 7 in V (F#) by a smooth major 2nd. That avoids the augmented 2nd that would have resulted between Eb and F#.

But then again, we so often get only the first phrase of the theme in the films themselves that the major IV can start to sound Dorian, or simply like a major-mode colouring of IV. It all depends on whether one has the whole theme in mind when hearing it. In other words, do we expect to hear the following V chord and the rest of the 2nd phrase? If so, we’d probably be hearing the melodic minor interpretation. If not, we may well be hearing it as Dorian or an altered IV.

How do you hear it when the 1st phrase is on its own?

ah…sorry schoolboy error. and of course i’m forgetting that a crucial part of the dorian sound is the flattened seventh which is obviously absent in that D Maj chord ….which we hear twice. !

if the first phrase ended on the Cmaj…it would really sound like Dorian to my ears but the Dmaj makes all the difference , as does the Eb Maj . That means the Cmaj is just inspired flavouring I guess….

e

As a complete amateur who loves music, I have always wondered WHY and HOW certain scores in film create the mood and feeling that they do. Why do certain melodies and chord progressions and instruments create that yearning, or heroic, or comedic, or victorious feel? I stumbled upon this site, and, while much of it is over my head because of my own inexperience, it has already been informative and exciting to read! So, no, I do not agree with the person who feels you may be possibly wasting your time with such common scores (Star Wars, for example) such as are found in popular films. It is very helpful to us folks who would love have some of these curiosities explained, who don’t have time to go to school to study music (but would love to), and would most benefit from having familiar examples to refer to when learning. Thank you for this site! I am very much looking forward to spending some time here!

@Inels. Well said! Thank you, Mark. And keep up the great work!

Dear Mr. Richards,

I am currently writing my undergraduate dissertation on John Williams and how he uses music as a representational tool in his music for Jaws, Star Wars and Harry Potter. I am using Emilio Audissino’s book as a key reference throughout (as the first English book on Williams!) and a bunch of doctoral dissertations – but your website has been extremely helpful and certainly added insight to my own musical analysis! I love your metaphorical analysis of the Force theme. I had never thought of the melodic contour as a representation of the rebels’ struggle but it fits perfectly. I am using this page as effective argument in one of my chapters – and am referencing you throughout (as M. Richards – I initially thought I would have to use your screen name but ‘Film Score Junkie’ didn’t look that professional in my bibliography!).

Thank you very much for providing such an interesting analysis of the Star Wars themes.

best wishes,

Carrie

I like the force theme its awesome don’t u guys agree I mean its cool and awesome and also saaaaaaaaaaaad. U know the Binary Sunset it brings me to tears. Anyways. Hey FilmMusicNotes, do the blockade runner its in all of the movies.

You hinted at the more universal application of this theme’s evocation of “struggle”, but I think more can be said for the internal struggle which it signifies. Now that you’ve brilliantly illumined the melody’s “struggling” to reach the octave, but being temporarily knocked down a peg. I see the conflict between Luke’s wanting to go forth out into the galaxy and his hypercorrective rationality which he has learned from all his expectations constantly being too high–this rationality is of course, as Obi-Wan points out when he says “that’s your uncle talking” not the natural nature of Luke. That descending m6 interval sounds very much like a sigh. Luke has all these aspirations, but tries to ground himself to the earth (to Tatooine), even though he is in fact destined for the stars (so the melodic descending is quite a complement to a sort of “grounding in reality” while the ascending is evocative of “unrealistic” hopes of space and soaring and adventure)

When it hits that IV chord and the “hope” asserts itself, there’s no stopping the surge of “making a resolution” to own it and fight for this hope–a surge which Williams accentuates with that breathtaking change in dynamics during the Binary Sunset version. Then after the resolution is sealed on the heroic VI chord, the mind must sink back down to earth, not dejectedly, but bringing with it a renewed commitment to bring into reality that which is hoped for. The last P5 (not present in the Binary Sunset) can be seen as a sort of “whispering” the promise one last time before moving back to business.

Perhaps this only works for the Binary Sunset scene, as a specific application of the more universal “struggle–>hope–>climax” scheme y’all laid out. But as the theme of the Force, I’d warrant that there will be a lot of this introspectiveness in its reiterations. After all, mastery of the Force is a sort of coming to terms with the self.

Thanks for this detailed interpretation! I think we understand this theme’s meaning in the same way. It’s true there are several iterations that are more introspective in their association, as when Yoda explains to Luke the nature of the Force in The Empire Strikes Back, or in Return of the Jedi, when Luke asks Leia what she remembers about her mother, or in Revenge of the Sith, when Yoda tells Anakin not to fear the loss of a loved one. So, yes, I think the introspective application of the meaning works in many different iterations of the theme. Thanks again!

I agree that the major IV harmonization of ^4 is poignant and the most common. In The Force Awakens, I heard ^4 harmonized by major flat-II (Neapolitan), which I hadn’t heard elsewhere in Star Wars. I think it was after the saber discovery. It’s not that original an idea (it’s another example of how much Williams owes to Beethoven), but in this context, I hear the major-triad-as-hope part of bII to be shadowed by the chromaticism (especially flat-^2) as loss or nostalgia, which was a huge part of Episode VII. Here’s another odd harmonization of ^4 that kind of combines the two, like a VI(add b3, add #4). Listen to the beginning of https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzLMu6Kqjt4. (Also, in this link 0:40 has an uncomfortable bII) Was that in any of the movies? If so, where?

Hi Gabe, and thanks for your insights. My post on uses of the Force theme addresses harmonizations of ^4 with flat II. It also occurs in Return of the Jedi as Vader picks up the Emperor and does away with him down the pit. I haven’t had a detailed listen to The Force Awakens yet, but I will be doing a post on it soon, so perhaps I could address some of the old themes like the Force theme there. Loss of nostaglia, you say? Interesting! I’ll have to ponder that. Thanks again!

I love Star Wars OST, specially this theme. Thanks for your analysis on this theme, I was wondering if this little piece of music caused the same feelings on others as it does on me, a mix of sadness and struggle until becoming a hero or doing something heroic. It´s wonderful. Greetings from Panama.

Hi Erika – thanks for your comment. I know that this theme is very highly regarded among film music fans, and certainly the fact that this theme appears more than any other in the Star Wars saga (even the main theme!) seems to indicate that it is a highly effective theme. Even Episode VII used it a number of times in some very prominent places, so the tradition continues. Along with the main theme, I’d say it’s the strongest theme in all the Star Wars scores.

Mark,

I simply loved your analysis. It feels so good to understand the meaning behind the creation of this extraordinary theme.

It was only after I found your website that I understood why I always enjoyed the Force Theme and how it was so beautifully crafted. I also finally understood the interaction of these notes with the soundtrack of the new Star Wars movie, The Force Awakens.

I hope we can see an updated/revisited post about the new song “The Ways of the Force”, especially due it’s struggle to reach Idea 3, and the removal of Idea 2, going from Idea 1 to Idea 3 right during the climax of the movie (when Rey confronts Kylo Ren).

Thank you! Yes, a post on Episode VII is in the works, and I will definitely mention the old themes that reappear, including of course the Force theme, so stay tuned…

Thank you so much Mr Richards for your analysis !

As a JW lover myself, I am always delighted to read this kind of passionate and studious work. I’m sorry if I make some mistakes, I’m from France, but I’m really sincere.

It is wonderful to see the genius, humanity and wiseness of such a great composer. Because John Williams is, without any doubt, a great composer, thinking and building, but above all living the music he writes. He has never lost this gift, as we can hear with the music he composed for Star Wars ep7. I am very impatient to read your work on this new score, especially if you analyse the beautiful Rey’s Theme, which I’m sure is already full of hidden meanings in its ressemblances with the old themes we know.

Again, thanks a lot !

I hear snippets of essences. A very sad Johny come marching home. A Lonesome Taps. The Battle Hymn of the Republic. And parts of other songs from that time period whose titles long since forgotten. A mere touch of Amazing Grace. Pardon my rudeness. I never went for a higher degree in music as you clearly have. So our vocabulary may seem awkwardly opposed, yet I agree with much of what you have exposed. Excellent piece of deconstruction. Thank you for bringing it to our attention. (in addendum: I would add the following; the 1950s superman march theme ( George Reeves version) and the song, “House of the Rising Sun”. The Force Theme is an original, but it has many powerful influential compositional genetics on which to draws upon. I seem to hear old cowboy music in there as well, but I can’t at this time identify it/them. Possibly “The Big Valley theme.” with a touch of religious feeling.)

Pingback: Week 4 – ryandigitalmediatech

Some of the linked videos have been removed. Are there other youtube videos with that excerpt?

Thanks

Sorry about that, David. I found replacement clips and updated the page. Enjoy!

Hi, I would like to get a reference to put this on my essay(academic research).

Great article! Thanks,.

Hi Gabriel – exactly how to reference a site will depend on what citation style you’re using. Chicago Manual of Style is a very common one and is great because it’s so comprehensive. But whichever style you use, the main things you usually cite are: author, title, site name, site address, date accessed (since cites change regularly). Hope this helps!

Hi Mark. i just read your article in mtosmt.org and I loved it. I’m just wondering, in which category would you put this particular theme, sentence, period, clause?

Thanks!

Hi Luis – thanks so much for reading my MTO article! This theme was one I gave considerable thought and felt was deserving of a category that did not fit the traditional sentence, period, or hybrids thereof. In terms of the Force theme’s structure, I would say that bars 3-4 are a rather free variation of bars 1-2, especially with the initial rise through scale degrees 5-1-2-3 in both. Bars 3-4 then take the rise of bars 1-2 further as I show in the analysis. Bars 5-6 begin the same way as bars 3-4 then diverge again, producing another free variation. Finally, bars 7-8 promise closure to the theme with a cadential progression. Overall, then, I would classify the Force theme as a developing clause – in other words, based on an initial two-bar idea that is varied over the next two ideas. The division between 1-4 and 5-8 is produced by the rousing melodic climax up to scale degree 1 an octave higher, and in the famous “Binary Sunset” version, this division is further emphasized through the lush texture that emerges with bar 5.

Some readers may prefer to hear bars 3-4 as more of a contrasting idea, leading to a period-like first half (antecedent). But with Williams, variation of a two-bar idea within the very structure of the theme is part and parcel of his style, so I tend to hear it in the context of his other film work, which lends the developing clause further support.

In any case, thanks for asking such a great question!

Thanks for your answer Mark. It’s a very interesting theme indeed, and one of the most beautiful ever written. If you ever write a book about film themes please let me know to be the first one to get it. Greetings.

This deconstruction is beautiful and explores such a gorgeous theme that is very deserving of such an analysis imo. When i briefly studied the binary sunset section last year i was looking at the different modes that music can be written in and i thought that William’s use of a Dorian mode but in a minor key was really clever as it essentially is what gives it the atmosphere of hope, the raised 6th placing it somewhere between minor and major.

This is bloody wonderful. I’m with @Twit, the Force surges outwards and upwards in an attempt to go where it must. One of the main reasons I love that it is ‘The Force Theme’ rather than Luke’s Theme is it treats the Force as a living force (the sentence could quickly get very tautological), and mirrors its craving.

It is a joy to hear this every time.

Hey guys this not Dorian this is simple Melodic Minor.

The scale is G,a,b-flat,c,d,e,f-sharp,g. The IV is naturally a major chord as derived from the scale notes (C-E-G). Peace

Hi Robert. Indeed the major IV chord can result from a melodic minor scale as you say. In this case, however, that major IV ends the theme’s entire first phrase, so it is a cadential chord, a point of rest. So there is no need for its voice leading to be dependent on what follows since the phrase is already over and a new one can start afresh. This view is strengthened by the vast majority of the Force theme’s statements in Star Wars, Episode IV (but the other films as well) comprising only its first phrase, which retains the major IV at its end without any justification from a second phrase starting on V. I would also point out that even when the theme enters its second phrase after the first, the first phrase always retains the major IV even when the second phrase does not begin on V, as in this statement from Episode IV:

All this is to say that, while I can see how it may seem that the Force theme’s major IV is a result of the melodic minor scale, I think the evidence in the score suggests that it is rather a use of chromaticism that highlights its non-diatonic quality by not requiring justification with a following V chord. I would therefore say that such a use of chromaticism in Williams’ Star Wars scores is generally for the purpose of creating particular emotional expressions, whether it’s the benevolence of Yoda, Rose, and the boy Anakin through their themes’ use of the Lydian II# chord, the longing quality of love through the minor-mode iv and ii chords heard in Leia’s theme, Han Solo and the Princess, and Luke and Leia, or most famous of all, the twisted evil sound of the minor bvi chord in a minor key heard in Vader’s theme.

This is a great analysis thank you very much!! Do you have any idea what the final dissonant chord is? I’ve been struggling to try and figure it out but I cant seem to fully grasp it….I can hear the Db and the Fb/Enatural but I can’t hear the other notes. Thank you for this article Mark 🙂

Thanks, Katelyn. There’s definitely a G-natural and A# in the chord as well (the latter in the woodwinds). And I’m not entirely sure, but I think there’s also a G# buried in the middle somewhere (also in woodwinds, but faintly). So in total, it’s a C# diminished 7th chord with G# added to it.

Bravo! Without having a background in music, it can be difficult to explain how small pieces like this can evoke such powerful feelings. It’s a true pleasure to see how much thought went into every aspect of the Jedi/Obi-wan march.

I did a very short (and very rusty) melodic analysis of ET a couple of years ago and discovered that with these sorts of closed set themes, JW often places the highest note or climactic beats or significant harmonic change around the same location as the Golden Section (0.618 of the beat length of the theme). With this the high G4 is one beat after the GS point of this 33 beat theme..coincidence or an example of ‘classic’/classical design/proportion?

Although I don’t think he writes to a ‘formula’ as such it’s interesting that the repetition, development and shape of his closed themes seems to correlate with other classic closed themes – and popular ones at that.

Hi Dominic. Thanks for the thought-provoking question! In 2015, I published an article called “Film Music Themes: Analysis and Corpus Study”, where I analyzed nearly 500 main themes from Oscar-nominated scores ranging from the early 1930s to 2015. So when I consider the expressive arc of a theme, I think also of its structure in terms of theme types like sentences, periods, and the like. In my study, I analyzed E.T. as a structure called a “clause”, in which the initial idea of 2 bars is then restated or varied for 2 bars, then varied in a more striking way in the next 2 bars before coming to a cadence or close in the last 2 bars. Some other themes from the same era that have this clause structure are the main themes from John Barry’s Out of Africa, Jerry Goldsmith’s Papillon, and Dave Grusin’s On Golden Pond. Each of these melodies has a clearly highest melodic note, and if you segment them by their number of beats into the theme, as you do for E.T., here are the results for this highest (climactic) note: Out of Africa occurs at 19/32 beats (= 0.59 proportion), Papillon at 28/48 (= 0.58), and On Golden Pond at 38/69 (= 0.55).

All this is to say that I think that the placement of the climactic highest note in the E.T. theme coincides with a general principle in the theme’s structure, namely that the “clause” theme type easily lends itself to a climax around the 60% mark in the theme because that’s the 2 bars of the theme that break away from the pattern of the first 4 bars and frequently produce a climax before coming to a close with the last 2 bars. I’m not saying that Williams didn’t have the 60% proportion in mind when writing the E.T. theme, only that it goes hand-in-hand with the clause theme type, so probably he conceived of the two together, as if thinking “ok, this third time around with the idea, let’s bring it to a climax!”